Tracing the Ancestors

Historian, preservationist and Rice Architecture grad Jobie Hill ’02 documents and preserves slave houses — and the stories of those who lived there.

Winter 2025

By Kim Catley

Photos by Zach Phillips

On a warm July morning, I met preservation architect Jobie Hill ’02, ’04 in a small brick kitchen set in the rolling hills of Nelson County, Virginia. At the front of the room was a wide fireplace and a table holding a sound bowl, incense, candles and herbs — offerings for an ancestral veneration ceremony that would foster a spiritual connection with the enslaved people who once lived and worked on this land.

“Let us begin by inviting the presence of our beloved ancestors in this space,” the ceremony leader says. “May the vibrations of the sound bowl connect us across time and space, bridging the gap between past and present.

“Though their names may not be recorded — yet — or remembered in history books, their spirits live on in us and their descendants.”

The ancestral veneration marked the start of the first session of the Slave House Exploration and Evidence Tracing (SHEET) Field School, led by Hill. In the coming days, we would learn architectural, anthropological and archaeological techniques that would help uncover stories that have long been hidden — in the objects buried under the ground in front of us, and in the construction of the building in which we stood.

“People have a visceral reaction to a physical space,” Hill says. “To understand the landscape of slavery, you need structures. It’s impossible to understand the restraints, the confinements associated with slavery without physically experiencing it.”

‘Real people with real stories’

Located about an hour south of Charlottesville and the University of Virginia, Massies Mill is a small community named for the nearby wheat mill operated by the Massie family in the 1800s. The family owned several plantations in the surrounding area, including Pharsalia, now an event space with sweeping views of the Tye River valley and the Priest mountain.

A winding gravel drive leads to the complex of 20 buildings at the center of the 1,400-acre parcel Major Thomas Massie presented to his son, William, as a wedding present in 1814. At the time, Pharsalia was a working plantation that produced wheat, hops, tobacco, potatoes, apples, cranberries and ham, on the backs of enslaved people.

The Massies kept meticulous records about the farm’s production and crops, finances and enslaved people, totaling more than 100 years of daily memorandum books. Hill, whose research focuses on domestic slave buildings, says this level of detail about plantation life is rare. If records of enslaved people exist at all, they typically include little more than a list of first names.

“I’ve identified 1,336 names of enslaved people associated with Pharsalia,” Hill says. “These are real people that I can connect to real descendants today. They’re now more than just names; they are real people with real stories.”

Enslavers could control the materials, the size, the location, but the one thing they couldn’t control was the quality of the work. These houses were built by the same skilled people who built the main house.

Still, these records contribute to a history of slavery that is framed by the perspectives of the enslavers — not the people who appear on those lists. That bias is present today in everything from our history books to the limited study of slave houses. For more than a decade, Hill has been working to expand that narrative, marrying architecture, archaeology, anthropology and historic preservation to search for clues about enslaved buildings and the people who used them.

“Slave houses are often described as poorly built structures. But they’re hundreds of years old and they’re still standing,” she says. “We continue that pattern [of bias] if we don’t acknowledge the structures for what they really are.

“Enslavers could control the materials, the size, the location, but the one thing they couldn’t control was the quality of the work. These houses were built by the same skilled people who built the main house. The little things that show off their skill and resilience, their strength and perseverance, are hidden — but if you know how to look for them, you’ll see them.”

‘It’s important to know your past’

“To understand these structures,” Hill says, “you need a background in more than one thing.”

Luckily, Hill is an eager student. She started at Rice, where she earned a B.A. in anthropology and architecture as well as a Bachelor of Architecture. She added graduate degrees in historic preservation with an architectural technical teaching certificate and art history with a focus on Egyptian art and archaeology from the University of Memphis and the University of Oregon. Now, she’s pursuing a Ph.D. in history at Duke University, with Pharsalia as the focus of her dissertation.

Hill first surveyed a slave house when she was studying historic preservation, and that moment set the course for her career.

“I knew, this is what I’m going to spend my life doing,” she says. “Seeing the structure in person is so much different than reading about it or seeing a picture or a drawing of it. And as I kept learning, I realized that these buildings were incredibly misunderstood.”

In 2012, she founded Saving Slave Houses with the goal of preserving these structures. SSH maintains an international database of slave houses and aims to change the way people research and learn from them.

Two years later, she learned about an opening at Monticello, Thomas Jefferson’s primary plantation in Charlottesville. The museum was looking for an architect who specialized in slave houses to reconstruct Mulberry Row, a plantation street of 20 dwellings, workshops and storehouses used by the 400 men, women and children enslaved at the site.

“I thought, ‘What are the chances?’” Hill says. “I am setting out to be an architect that specializes in slave houses because that doesn’t really exist.”

She was hired for the position and is the architect of record for the reconstructed Hemmings Cabin. But the work required extensive research and surveys of other slave buildings. Her search for an example of a sliding sash window brought her to Pharsalia.

That’s how Hill met Foxie Morgan, a Massie descendant who owns Pharsalia with her husband, Richard. Morgan grew up 30 minutes away in Lynchburg, but she and her four siblings spent their summers at Pharsalia as their parents worked to restore the property. She met her now-husband in high school, and, after she finished college, they married on the front lawn. They moved into one of the property’s houses, where they raised their three children.

When Morgan’s mother died in 2004, the couple bought Pharsalia and turned the property into a wedding venue to help cover the expenses of restoration. Morgan, who has a passion for flowers, also hosts wreath-making and floral arranging workshops.

Morgan says she was aware of the history of the buildings, but they were mostly part of the landscape where she lived and played. As Hill pointed out details in the construction of the windows, Morgan began to see the buildings in a new light.

In the decade since, Morgan and Hill have developed a trusting relationship. Hill has more flexibility to let her research unfold than she would at a publicly owned site. And she connects the Morgans with additional resources that help them preserve the property and share its story with the public.

“Bad or good,” Morgan says, “I think it’s important to know your past.”

Hill’s research also led her to the Descendants of Enslaved Communities at UVA, where she connected with Nina Polley and Star Reams, descendants of enslaved people of Pharsalia. In 2020, they began talking to Hill about their family connections and potentially partnering on her research.

“We grew up listening to our grandmother Yvonne Hill Thomas’ oral histories. She was born here in Massies Mill,” Reams says. “She is a vivid storyteller and loves telling stories about her family. We’ve been working to validate her truth.

“Our first time touring some of the historical buildings was meaningful for us. It was also, at times, heartbreaking. But it helps you fully understand the magnitude of what life was like. It was a first step of reconciliation for us to acknowledge the historical trauma and honor the legacy of our family.”

‘Where do these stories meet?’

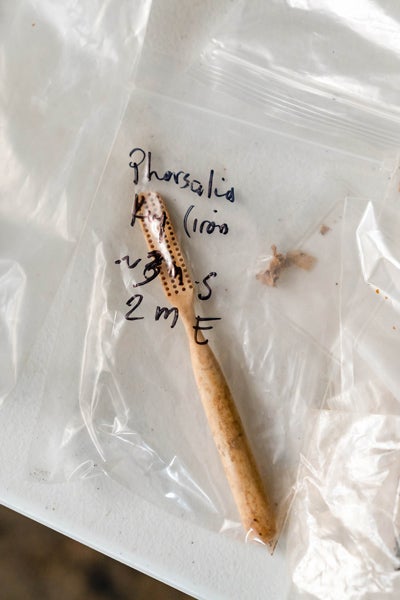

A few hours after the ancestral veneration ceremony, we returned to the brick kitchen with trowels, brushes and rulers in hand. We chipped at the concrete floor and gently brushed the dust away, revealing broken bricks and eggshells, a toothbrush and an old key.

Suddenly, someone called out, “Is that a wall?”

Everyone froze. Hill and archaeologist Tim Roberts inspected the sliver of stacked bricks revealed in the dirt before excitedly confirming the potential discovery. The following week, the second group of SHEET participants discovered additional rows of bricks that suggested the presence of two more walls. Roberts had previously scanned the ground with ground penetrating radar, which suggested the foundation of another building lay below. Now several layers deep, the pattern of the bricklaying suggested that finding was correct. They were possibly looking at the foundation of an earlier kitchen, one that was replaced by the kitchen-hospital quarter that stands there today.

“The archaeological act of going from top to bottom, it’s not like getting in a time machine and going back to 1865 or 1830 or 1814,” Roberts says. “There’s an awareness that we’re going to connect this all the way back. There’s a weaving [together] that happens in the process of investigation, and insights and inferences that come from having different people involved in the work.”

Pharsalia will continue to be Hill’s focus for now, but unexplored slave houses exist across Virginia and the U.S.

Basic excavation techniques are some of the many skills Hill has incorporated into the SHEET Field School — an idea she’s been honing for years. When she was on the board of the Vernacular Architecture Forum, the organization received funding from the Mellon Foundation to develop field schools focused on African American sites. Hill was given the choice of planning the application or stepping down from the board and applying herself. She stepped down.

SHEET was one of three field schools selected, and Hill held the first of two seasons this past summer. The concept is based on architectural field schools, which typically focus on measured drawings of buildings.

“But slave houses are usually just a square or rectangle,” Hill says. “That doesn’t tell you a lot.”

Instead, the weeklong intensive brought together archaeologists, architects and historians who offered demonstrations in excavation, photography and, yes, measured drawing. Among the participants, Hill gave preference to descendants of enslaved communities, but otherwise they came from a range of backgrounds and no previous experience was required.

“I wanted to show people you can have a background in anything and be involved in the storytelling of history,” she says.

As they learned core skills, participants also contributed important work to the research at Pharsalia, which hasn’t received the same resources as sites like Monticello. The measured drawings produced during the field school will eventually land in the Library of Congress. And Hill expects next year’s field school to focus on hands-on preservation as participants address building repairs.

Hill hopes SHEET will lead more people to find a way to contribute to the study of slave houses. She also wants to create a template for field schools across the country, with participants becoming trained facilitators who can pull from a growing network of experts, descendants and property owners to support their own site-specific projects.

Pharsalia will continue to be Hill’s focus for now, but unexplored slave houses exist across Virginia and the U.S. She hopes to eventually connect with more property owners who are committed to understanding the full history of their land — and to making that story accessible to others.

“That knowledge doesn’t just belong to property owners,” Hill says. “It involves many other families. It belongs to hundreds of thousands of other people. If you’re going to do [this research], you need to share it with everyone that it involves.”

Morgan and Hill are already working toward that goal. Collections of Massie family papers and plantation journals that document in great detail the lives of the people they enslaved are available at several museums and universities, and Hill is helping to digitize their contents. Hill and Morgan are also joining the National Park Service’s African American Civil Rights Network, which could provide resources for more robust tours at Pharsalia. And the involvement of descendants like Reams and Polley has added a deeper level of nuance and connection that spans generations.

“Descendants [of both enslaved people and the Massie family] are starting with themselves and researching backward to trace their families,” Hill says. “I’m starting historically and trying to move forward. And there’s the built environment.

“They’re each telling a story. It’s a little bit different, but it’s the same story. That’s the part I’m fascinated with: Where do these stories meet?”

INSIDE THE SYLLABUS

A multifaceted approach to studying slave buildings at the Field School.

History

A tour of Pharsalia and surrounding area, including Tyro Farm, Massies Mill, Oak Hill Cemetery and Level Green plantation.

Storytelling

Using film to understand historical trauma in communities of color, led by film producer Frederick Murphy.

Archaeology

Presentation on the role of archaeology followed by excavation practice, led by Tim Roberts, owner of Black Star Cultural Resources.

Building archaeology

How to study the architecture of slave houses and what buildings reveal about enslaved people, led by Jobie Hill.

Documentation

Demonstration and practice with measured drawings, laser scanning and photography, led by architects and interns from the Historic American Buildings Survey.

Anthropology

Hearth cooking demonstration and lunch featuring foods available to enslaved people, led by food historians Jerome Bias, owner of Southern Heritage Furniture, and Lyslee Duncan (session 1) and Leni Sorensen, owner of Indigo House, and Liz Beamon (session 2).

Preservation

Steps to preserve the kitchen-hospital quarter, led by engineers from Springpoint Structural.

Oral histories

Engaging with Pharsalia descendants, both from the enslaved communities and the Massie family, listening to and learning from their family stories.

Watch a a short video about the 2021 Descendants' Workshop, which was part of the Virginia Black Public History Summer Institute. The institute was directed by Jobie Hill '02, '04.