The Climate Diplomat

Andy Karsner brings a singular voice and depth of commitment to the challenge of building a sustainable energy future.

Winter 2025

Interview by Russell Gold

Photos by Nico Ovid

In his final semester at Rice, Andy Karsner ’89 took a political science course wherein he studied the political economy of East Germany and the Soviet Union. A few weeks after graduating, he was in Berlin tearing down the Wall, which physically signified the downfall of communism.

That experience taught him a valuable lesson — that change can happen even when the status quo is set in stone. “It just really opened me up to the realization that things aren’t always as intractable as they may seem,” he says.

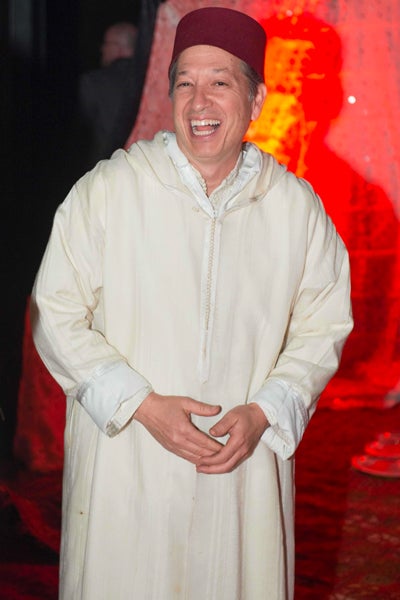

Karsner has spent his peripatetic career surfing wave after wave of change in the energy industry. He developed oil and gas-fired power plants in Pakistan and the Philippines, pioneered wind farms in Morocco, started companies, negotiated global climate accords, made far-sighted technology investments, and served as assistant secretary of energy in the George W. Bush administration. Today, he is senior strategist — dubbed “space cowboy” — for Alphabet’s Moonshot Factory, and if that wasn’t enough, Karsner also serves on Exxon Mobil’s board of directors.

On a recent morning walk around Lady Bird Lake in downtown Austin, we talked about energy, climate, technology, world travel and how to construct a fulfilling career. Karsner suggested we talk while walking. It seemed apt; in the three decades since graduating, he hasn’t stopped moving. He joked that if he ever slows down enough to write a memoir, he plans to title it “Backpacker in the Boardroom.”

Russell Gold: You don’t have an MBA. You don’t have an engineering degree. How did you end up building power plants in your 20s?

Andy Karsner: What I did have was a mountain of school debt and the need to pay it off. In those days, Houston’s economy wasn’t really as diversified as it is now. So, if you weren’t heading off to be a rocket scientist at NASA, somebody on Wall Street or a consultant, then the probability was you’d be in the energy industry.

RG: If you hadn’t gone to school in Houston, do you think you would have ended up in energy?

AK: It’s hard to say. I think of energy as a conduit of impacting and evolving human systems. If I had gone somewhere else, would it have been about water? Clean air? I think I always had an itch to do something of consequence in the world. The opportunity bred the obligation. I’m a bit of a systems thinker, so I think that energy is such a common touch point across how we live and where we work and how we play, and how we measure our significance, affluence or lifestyle — and now, how we measure our risk and the probability of sustaining ourselves.

RG: What do you mean by obligation?

AK: It’s really the thing that my father sought to impress most on us: that liberty comes with responsibility. They’re in equal measure. And that your opportunities breed an obligation. And that obligation is to serve others, serve community, serve your country, serve your fellow humanity.

RG: In 2021, you were part of an insurgent slate elected to the board of Exxon Mobil. Three years later, what do you think you have to show for this insurgency? Have you been able to effect change? I think of energy as a conduit of impacting and evolving human systems. If I had gone somewhere else, would it have been about water? Clean air? I think I always had an itch to do something of consequence in the world.

AK: Well, it’s larger than my efforts solely; pursuing change successfully is a collective exercise. The number one change you make is to help people understand that it wasn’t meant to be a binary outcome. There were lots of people who perpetuated the mythology that we were going there to blow up the company, to have a solar-panels-everywhere policy by one of the world’s largest oil and gas players. What we were trying to do was change the performance and outcomes of a company by altering its strategy and strengthening its capacity to be more accountable and to better account for the probable future we face.

And as it turns out, in business, the greater precision you have in a thoughtful strategy, the greater the probability you have of profitability and positive impact. And that has happened for Exxon. Making profits to a company is like health to each of us individually. We need it to survive; the more of it we have, the stronger we are; but it isn’t why we exist! And what’s actually happened in those years since [I joined the board] — and I credit the management team and employees and not just the slate of us that came aboard, but really the whole board — is ultimately hashing through and coalescing around a strategy that reorganized the company.

Exxon consolidated and co-located its executives and employees, relocating the headquarters from Dallas to Houston. That simplified its structure and amongst other efficiencies, elevated the role of one of the three new legs of the company called Low Carbon Solutions. Now Exxon is one of the largest investors — if not the largest — in low carbon solutions such as carbon capture and sequestration and low carbon alternative fuels.

And for a company that wasn’t perceived to be as engaged on the issue of low-carbon emissions management, to go from sort of worst to first by most measures of investing dollars for carbon molecules management, it’s been a key shift that has been welcomed by most parties.

RG: Alphabet’s innovation lab is called the Moonshot Factory. What’s the point of a moonshot factory? Is it to create a world-changing technology, or is it to generate enthusiasm and optimism?

AK: You cannot have one without the other. That’s why Kennedy’s speech [“We choose to go to the Moon,” delivered at Rice in 1962] is the greatest science and technology speech in the history of the American presidency. He challenged us to do something well beyond existing capability. He gave us a very specific timeframe, an urgency that we should do something that is beyond anyone’s imagination. And that’s completely analogous to where we are today managing our climate challenges.

A moonshot is a bet. It’s placing a high-risk/high-reward wager on society’s table. It’s a willingness to take enormous risks that come at an enormous price. Our endeavor to bend what is possible and to realize something greater for our species, for our fellow men and women on this planet, is an important and relentless aspiration.

RG: Let me ask you to play a futurist or job counselor. Someone comes to you and they’re interested in energy. What technologies do you see out there that excite you?

AK: When I left government, I would have thought that fusion wouldn’t arrive in my lifetime. Now, I believe fusion, if I live long enough, will arrive in my lifetime.

RG: You seem to be very optimistic about technology.

AK: We are in a battle with ourselves every day to find our higher angels, both individually and collectively. A hammer is technology. A hammer is something you can hand to your neighbor and share and build a home together. Or it can be a murder weapon. Technologies aren’t moral or immoral, they’re amoral. And what we do with them is what defines us as a species, or as a nation, or as a community and even as a family.

So you’ve got two different things you’ve got to keep distinct. There’s our consummate need to move forward and develop the tools and technologies to disseminate goodness at a rate that exceeds our propensity to do bad things. And then you have the need to apply some morality on how these tools ought to be used. Ethics haven’t caught up yet with CRISPR and AI.

We haven’t even caught up with big data and the power of our capacity to compute, in terms of our moral and metaphysical reckoning of how these things are going to integrate into our society. I still call upon my undergraduate religious studies at Rice to navigate this inevitable intersection.

RG: You’ve worked in government; you’ve worked as a CEO and as an investor. You serve on boards. How deliberate would you say your career has been? Did you seek out and say, okay, now is the time to go into government and figure out how government works? Or was it more just randomness of opportunities?

AK: I think it’s closer to the latter than the former. It’s the reason why I’m a terrible speaker at MBA classes. I always get asked to teach a course or lecture and inevitably it comes with the question: How do we follow your career? And I just view myself as the Forrest Gump of energy — lots of pachinko machine balls going down into the right column when they could have gone down the other column. I’m a lucky guy: Right place, right time. But it’s also what you make of the luck that you get.

So I think it’s more important to understand what true opportunities look like and blend them in with your own passions, drive and mission and meet at the corner of purpose and productivity. And then kind of everything else falls in place. The money follows, the positions follow, the titles follow. But if you get consumed with those things, you might subordinate your compass. That has to be your guide, more than credentials.

RG: There’s a Shakespeare quote you like from “Hamlet” where Polonius is talking to his son. It’s a famous quote: “To thine own self be true.” The second part of that quote is a little less known. “Thou canst not then be false to any man.” So, at the risk of sounding cynical, what’s so important about honesty in business and life in general?

AK: It’s not cynical. That is really my top advice for my children. It’s not merely to be honest — it’s to be honest with yourself. It’s to be authentic to who you are. That’s what it means to me. To thine own self be true.

Have a curious mind and bring in different and informed peripheral inputs as far and wide as you can, but develop your core and know who you are. It is hard for people to be efficient in exercising their best self or finding their highest aspirations, let alone realizing them, the longer they dwell in the judgment of others rather than find their own inner compass and calibrate it for what their true north looks like.

If you believe you can never put a price on nature, that’s just abdicating the field to self-destructive systems, and that must be corrected for us to avoid worst outcomes.

RG: One of the themes in your professional life is valuing nature and figuring out how to put a price on it.

AK: You need to put a price on it. There are those who would walk through the woods and recite the old Mastercard commercial and say, “It’s priceless.” Because spiritually it is. It has its own intrinsic value. Of course it’s priceless. It’s sacred. But we live in a world where trading systems have organically sprung up from our societies. The magnitude of the challenges we face environmentally mean that you can’t live under the mythology that nature is priceless, because people put a price on it every day. They put a price on it for lumber. They put a price on it for mining; they put a price on it for oil and gas. We do things that exploit and extract from our environment every day and put a price on it with incredible efficiency. So what I would really like to have is a system change where we internalize the value of nature, where we understand the cost and opportunity cost of depleting it, and we account for it on the ledgers of our companies and our societies. The price, the cost and value of nature should always be worth more thriving and alive than unhealthy and dead. If you believe you can never put a price on nature, that’s just abdicating the field to self-destructive systems, and that must be corrected for us to avoid worst outcomes.

RG: Let’s go back to the Moroccan wind farm. Your mother is from Casablanca. Was she Moroccan or was she part of a diaspora that was moving through Morocco?

AK: She would absolutely consider herself Moroccan. My mother always kept a picture of the king of Morocco in our house. As a kid, I found it embarrassing to explain. It was already enough my mother would speak in French in front of my elementary school friends … but my mother lived in Casablanca at the time that the Vichy French and the Nazi collaborators were occupying Morocco. That was the first eight years of her life. According to my mother, when the Nazis demanded Sultan Mohammed V turn over the Jews, he replied, “We don’t have any Jews; we only have Moroccans.”

I’m very proud of that Moroccan heritage. And I’m even more proud of that multicultural diaspora. Not just of Jews from Iberia who were pushed out with the Inquisition, as my ancestors were, but also of Arabs who arrived in the seventh century, who lived with a significant majority Berber indigenous population. I view the Earth — both humanity and nature — as our shared treasury: It’s our endowment, and it’s up to us not to recklessly deduct more of the principal, but to try to live off the interest as good, responsible stewards and grow the inheritance for future generations.