The Wine Writer

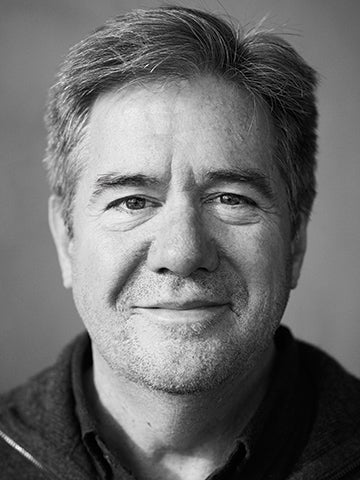

Alumnus Ray Isle has traveled the world to bring us a book on artisanal and sustainable wines.

Winter 2024

By Julie Case | Photography by Mike McGregor

The wine is copper-hued and hazy and briefly gives off the distinct “natty” aromas often associated with natural and skin-contact wines, and Ray Isle ’86 is giving it an appreciative swirl. The place is the events room of Japanese restaurant Rule of Thirds, lined with blonde wood and pale modernistic chairs, and Isle has just descended from the mini stage, where he’s been moderating a master class for wine-loving Brooklynites about biodynamic winemaking and natural wine.

Isle, of course, knows a thing or two about wine. The executive wine editor for Food & Wine magazine, he is one of the best-known wine writers in the country and among the top wine writers in the world. But 25 years ago, when Isle was just getting into wine, the natural wine movement was just beginning — he could not have imagined that he would write “The World in a Wineglass: The Insider’s Guide to Artisanal, Sustainable, Extraordinary Wines to Drink Now” (Scribner, 2023), a Jeroboam-sized book about the stories of sustainable wines and winemakers from around the globe.

On this occasion, the wine in Isle’s glass is a biodynamic Cecilia rosé by Austrian winery Gut Oggau, whose co-founder Eduard Tscheppe has just been part of the master class. Isle dips in for a taste and comes up with a grin. “It’s a weird-ass blend of red and white grape varieties from one single plot,” he says, admiring the wine’s textural qualities that come thanks to its prolonged contact with macerated grape skins. “It also has this beautiful silkiness to its texture, which rosé doesn't always have.”

The nice thing about wine is that you’re constantly learning, because it’s inexhaustible. It’s agriculture, and it’s business, and it’s hedonism, and it’s cultural history.

Isle’s path to executive wine editor and wine writer was hardly a direct one. Born and raised in Houston, where his father, Walter W. Isle, taught English at Rice from 1961 to 2007 and his mother, Brenda Isle, was an ice dance instructor, Isle always knew he wanted to be a writer — he just thought it would be novels.

“I spent zero through 30 not being that interested in wine. My sole memory of wine at Rice was lying on the floor at a Rice Players’ party and having someone pour wine into my mouth from a bag in a box,” says Isle with a dry chuckle. “Apparently that’s the lead-up to being a wine writer.”

After earning a B.A. in English at Rice, Isle studied creative writing at Boston University, then got an offer from family friend and Pulitzer-winning author Larry McMurtry ’60 to work in his Washington, D.C., rare books store. While there, a waitress he was dating started bringing him bottles of wine to try, and his interest in wine took hold. As he waited for customers to walk in the door of Booked Up, Isle read about wine. Soon, he began purchasing the $14 bottles his meager salary could afford. There were discoveries: Freemark Abbey’s Bosché vineyards on a splurge; a half bottle of Château La Tour blanche Sauternes. “That was kind of an extraordinary experience, in that I had never had Sauternes before,” he says.

Still, wine would likely have remained just a curiosity had Isle not landed, in 1993, the prestigious two-year fiction-writing Wallace Stegner Fellowship at Stanford University, in the foothills of America’s best-known wine region. Soon, he was making pilgrimages to wine country. Before long, he was traveling regularly to Napa to help with bottlings on the weekends (and getting paid in wine). By the time he finished his program at Stanford, Isle was fully fascinated not only with the wine in his glass but also with the whole world of wine — from soil profiles to cultural histories. He was also sick of the infighting in English departments. “All these people are bonkers,” he thought. So, he left academia and started life in the wine business.

Love, in the form of his girlfriend, Cecily, whom he would later marry, took Isle to New York City, where he engaged in the thankless business of selling port. By day, he lugged bags of wine around the Big Apple; by night, he finished a novel (that “probably justifiably” did not sell, he says) and freelanced for magazines. Which is how Isle ultimately became a wine writer: not just by being an oenophile, but by being a journalist. In 2005, he landed at Food & Wine magazine, rising to executive wine editor in 2009. After years of scoring and reviewing wines, he focuses now on writing feature stories and making wine recommendations and pairings. He also no longer cares as much about writing fiction.

“I still have a number of friends who are novelists from, or who were in, the Stegner program at one point or another, some of whom are quite successful, but they spend a lot of time sitting in rooms by themselves, working,” says Isle. “With wine, there’s the writing part, but there’s also the visiting vineyards, and going places, and learning, and meeting new people.”

He also discovered that from a writing standpoint, facts are as interesting to him as fiction, and that he loves the perpetual erudition required by wine. “The nice thing about wine is that you’re constantly learning, because it’s inexhaustible. It’s agriculture, and it’s business, and it’s hedonism, and it’s cultural history. And it goes back thousands of years. And it changes every year, because each vintage is different, and new regions come online, and old regions kind of fade away, and the people change. It’s just a great topic, if you want to write about something.”

A Taste for the Earth

Even as Isle’s writing passions were changing, so were his interests when it came to wine.

“In the past, there was a kind of paradigm of what constitutes great wine that maybe doesn’t take into account the things people care about more now,” says Isle, noting that younger audiences are interested in questions about exactly how, and with what values, wines are made. Weighing those questions is a very different way to evaluate a wine than making a choice based on a point score.

Isle began to feel that those questions were worth pursuing, and before long, he realized he had found the subject of a book — one that would tell stories about oddball winemakers and fastidious grape growers. He wanted to write about farming and terroir, organic and sustainable viticulture, and about farming practices that obsess over a vineyard’s underground microbial life. He wanted to write about how such wines often hum with energy and vibrate with life.

I’m more and more, over time, interested in being in the vineyard and trying to understand how that place is manifested in the wine.

Over the course of 700 pages, Isle tells the stories of 262 wine producers who make great wines that express the places those wines come from and who, with relatively few exceptions, live on the land they farm. He tasted every wine mentioned in the book, whether during the more than two years he spent writing it or during earlier research for other stories, and he personally spoke to or visited — or both — every winery and winemaker referenced.

Here is Clare Carver of Oregon’s Big Table Farm, with her Luddite horses and her story of being run over by her own cow. Here are Gut Oggau’s Eduard and Stephanie Tscheppe-Eselböck reclaiming an abandoned farm and explaining that biodynamics is how to reach balance in the vineyard. Here is Languedoc’s Gerard Bertrand bemoaning the disaster a liver problem is for a Frenchman.

Isle doesn’t necessarily buy into every trend he writes about — one element of biodynamic winemaking is to fill a cow horn with manure and bury it underground until the planets properly align — but he is clear that as much as climate, exposure and geology play their parts in creating a sense of terroir, so does the microbial life of the soil. It helps determine why a wine from one place tastes distinctively different from the wine made from grapes just a stone’s throw away.

“I pretty much banned looking at tanks and bottling lines. Barrels are still kind of interesting, but I don’t know, the vineyards … ” Isle trails off in a way that leaves the listener imagining rolling vine-covered hillsides glowing in sunlight. “I’m more and more, over time, interested in being in the vineyard and trying to understand how that place is manifested in the wine.”

Even now that the book is on shelves, Isle still travels to some pretty appealing places for work — to taste wine and chase stories. Between June and November of 2023 alone, he went to California, Sardinia, Bolgheri, the Languedoc area of France, the Lombardy region of Italy and Charleston, twice — all for wine or wine-adjacent work. This fall, he and his wife, Cecily, even got to help their daughter celebrate her 21st birthday in Italy. With Champagne.

And while over the decades Ray Isle may have gone from budding novelist to slinger of facts, he has remained a storyteller. With “The World in a Wineglass,” Isle has taken what could have been a dull encyclopedia and returned with stories of real people tending real places and making real, artisanal wine. His book could become the No. 1 natural wine lover’s reference. It’s a tall order, but one he has delivered on with effervescence and energy and joy — manure-filled cow horns and all.

A Flight of Wine Recommendations

Isle’s worldwide tour of “artisanal, sustainable and extraordinary wines” stops at off-the-beaten-path, independent wineries in Europe, the United States and the Southern Hemisphere, and each stop yields unique recommendations.

Here are just a few.

A region famous for wine: Bordeaux may be the most famous wine region in the world, Isle says, home to superstar chateaux and expensive wines. Yet, wine drinkers should note that the same region is home to smaller, independent producers — “one of the world’s best sources for affordable, excellent reds.” Recommended: Château Bourgneuf in Pomerol is home to the Vayon family, owners for eight generations of a certified sustainable winery that produces two wines: Saison de Bourgneuf and Château Bourgneuf.

Independent and environmentally aware: California wines dominate the U.S. market. “Its vineyards … stretch across 147 American viticultural areas,” writes Isle. Experimentation is rife in this less tradition-bound wine-growing state, and there’s no single defining style for producers or consumers. Spottswoode in Napa Valley, founded way back in the 1800s, is the “first winery in the appellation to certify its vineyards organic.” Recommended: Spottswoode Napa Valley sauvignon blanc, Lyndenhurst cabernet sauvignon and Spottswoode Estate cabernet sauvignon.

More to a familiar name: Rioja, Spain’s most famous wine region, is composed of small family farms, writes Isle. There are thousands of growers, but many fewer wineries. He sees a movement in the area toward more organic and sustainable practices. R. López de Heredia in Rioja, founded in 1877, is a vineyard steeped in tradition and respect for the family’s land, skill and heritage. Recommended: An affordable Viña Cubillo crianza and the vineyard’s flagship wine, the Viña Tondonia reserva.