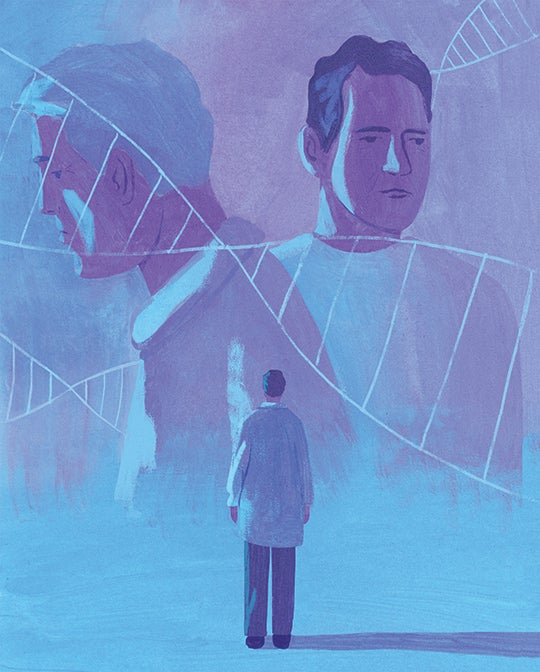

Kindred Spirits

Oncologist Mark Lewis developed a rare cancer and found another connection to his family and patients.

Winter 2024

By Dr. Mark A. Lewis '01

For as long as I can remember, I’ve always wanted to be an oncologist. But I never suspected that the first patient I’d diagnose with cancer would be me.

On the first morning of orientation for a three-year fellowship to study the treatment of cancer, I awoke with a knifelike pain lancing my side. I already held an M.D. and had completed four years of medical residency, so I reflexively triaged myself as I would any other patient: Was the discomfort localizing to the lower right quadrant of the abdomen, like appendicitis? No, nor did I have a fever. Was it slightly higher, under the rib cage, like an inflamed gallbladder? Not quite. Was it an extreme manifestation of the “nervous stomach” that can plague apprehensive public speakers and jittery fledgling doctors alike? Possibly. Only further testing could distinguish psychosomatic from visceral causes. As the name of the discipline implies, internal medicine is an incisive exploration into what ails the body within.

Fortuitously, I was training at the Mayo Clinic, a world-class health care facility with every diagnostic tool available to arrive at the correct explanation. Scans revealed tumors in my pancreas, an alarmingly personal entree into oncology. But, just as tellingly, my bloodwork showed a high calcium level, or hypercalcemia. It was that test result that sparked an epiphany, because it was an electrolyte disturbance that afflicted my father as well, prompting painful, stabbing kidney stones.

It was his even more agonizing death from a mysterious cancer when I was 14 years old, however, that traumatically catalyzed my interest in the medical field. At the time, it had appeared to be an inexplicable tragedy: a clean-living man felled before his 50th birthday by “the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune.”

As two points make a line, my diagnosis connected me to my dad not only by a cryptic loss but also by a quantifiable and shared metabolic anomaly. The physician’s descriptor for an unknown cause of illness is “idiopathic,” an elegant Greek-derived shorthand for an etiology that eludes a would-be detective hunting for both culprit and remedy. I had acquired a tiny clue by which to reopen an investigation into my father’s untimely passing.

Although it was still early in my career, I had just enough aptitude to know that there were only two heritable conditions that would cause hypercalcemia in consecutive generations: one entirely benign and the other a more sinister mutation that could precipitate deadly tumors as well as jagged crystals in the urine. In the process of elimination, my head needed only to consult my still-grieving heart to provide the answer.

Family history

I have likened this moment of revelation as akin to stargazing and suddenly discerning a constellation amid the lights in the firmament. Rather than peering through a telescope at the heavens, however, I was assessing my own family history as if exhuming one grave at a time. My investigations took me searching beyond the death of my father, which I’d witnessed firsthand, to reconstructing the downfall of the paternal grandfather whom I’d never met.

Our relatives helped me piece together his story. He had been one of the most prominent ministers in Belfast in the ’60s and ’70s, known especially for the power of his preaching. The first sign of his undoing had been dysphonia, a vocal disturbance that changed his timbre and threatened to silence him; as his speech faltered, it became more suitable for the whisper of private prayer than a booming homily from the pulpit. An operation on his throat briefly restored him to full volume before he developed difficulty swallowing in autumn 1977, indicating that a lesion lower than his larynx was impinging on his esophagus. Soon after, debilitating pain indicated metastases to the spine. Then he lost the plot during a sermon, heralding the spread of malignancy from his bones to his brain. By summer, he had lapsed into a coma before dying at the age of 64.

I was born the following year and, when I was old enough to learn about him, was taught that, outside of his obvious significance to his parish, he had been important to the peace process in Northern Ireland. When his country was riven by the sectarian violence of the Troubles, he tried to heal the fractures by spreading and embodying the gospel.

The quieting of his pastoral rhetoric had indeed been far more foreboding than laryngitis. As if performing a bloodless autopsy, I could see in my mind that a cancer must have blossomed in his chest like a bad seed rooted behind his breastbone, compressing the nerves to his voice box; that specific anatomy fit the pattern I was increasingly recognizing as multiple endocrine neoplasia, Type 1, or MEN1, an esoteric condition affecting various and sometimes obscure glands.

The thymus, one such gland located behind the sternum, is an organ that serves no known physiological purpose in the adult body — it seems to exhaust its usefulness after harboring lymphocytes during the early instruction of the pediatric immune system — so it is a maddeningly vestigial tissue to kill a grown man. Yet I became convinced that it was the cellular site of origin for both my grandfather’s and my father’s “idiopathic” tumors, inspiring my hypothesis that our family curse was in fact a rare but defined cancer syndrome.

During my undergraduate years at Rice, I studied ancient Greek in an effort to be more like my dad, who studied classical languages to aid his exegesis of Scripture as a preacher himself. While I did not hear the call to follow him and my granddad into the ministry, I found an understanding of Hellenism helpful in decoding the vocabulary I encountered in my medical career, wherein every initiate utters the Hippocratic oath. And so I revisited the etymology of “idiopathic,” summing ιδιοσ (“idios,” one’s own) and πάθος (“pathos,” suffering) to at long last dispel the uncertainty that had enveloped my forefathers’ ends: MEN1 was the name of the pox on our house.

I have since developed a pet theory that cancer is an occupational hazard for oncologists not because we are exposed to excess radiation or other mutagens in the environment but because so many of us are drawn to the specialty through the loss of first-degree relatives to the disease, potentially indicating risk at a genomic level. My own hereditary predisposition to tumors is as much a part of me as my eye color, with far more profound consequences than my appearance. The depth of genotype trumps the superficiality of phenotype. This is simply who I am meant to be.

A patient and a physician

I am a patient-physician, always inhabiting the front part of that phrase, and every day of my oncology career has been filtered through an unavoidably bisected mind which holds objective facts on one side and embodied experience on the other. The former is a function of the higher cortex, where I can cogitate about science, whereas the latter is a repository of often-painful memories through which I can empathize with the suffering of those under my care. I will never forget, for instance, the deep cuts of the scalpel by which surgeons excised the most threatening tumors in my pancreas. Of all the operations I witnessed as a medical student, none were as indelibly instructive as when I went under the knife myself.

“Gnosis,” the Greek word for knowledge, forms the suffix for so many of our thought processes in medicine — the largely deductive reasoning by which we identify precisely what vexes each patient from among a vast number of possible maladies, a sort of informed prophesy, like modern oracles. But “pathos” appeals more to feeling, and this is what our patients seek to communicate. Their understanding of illness is different than that of most health care professionals, acquired not through medical school, postgraduate training and clinical practice, but through dwelling in a stricken body. It is the same gaping difference between a birdwatcher’s and a hawk’s comprehension of flight. The raptor feels the air beneath its wings, rides the thermals, instinctively plots its angle of attack. The doctor, like the birdwatcher following a trajectory, is limited to observing the disease course without sharing in the experience.

This sense of always being at a slight remove — a perpetual outsider looking in — has particularly irked me as an oncologist. In truth, most cancer doctors know not quite what they say when they talk about chemotherapy. We are akin to teetotalist bartenders slinging artisanal cocktails, pulling ingredients off the pharmacy’s top shelf without absorbing the full impact of our mixology.

As a patient, I have not yet required chemo, although a taste of my own medicine may still await. In the meantime, I feel forewarned by the losses of my father and grandfather, as well as a strange sense of inevitability around my choice of vocation, much as it differs from theirs. Although I don a white coat instead of their clerical robes, I must wonder if this, too, has been ordained.

Mark Lewis is the director of gastrointestinal oncology at Intermountain Healthcare in Sandy, Utah, where he lives with his pediatrician wife, Stasha, and two children. He graduated from Rice in 2001 with a double major in biology and ancient Mediterranean civilizations. His book in progress is tentatively titled, “Fearfully and Wonderfully Made: A Pedigree of Cancer.”