Unconventional Wisdom: The Builder

Paul Cherukuri in his own words

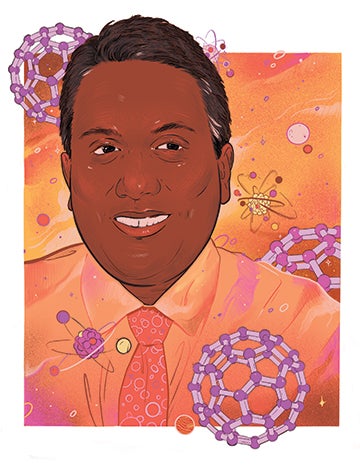

Last summer, Paul Cherukuri ’07 — physicist, chemist and medtech entrepreneur — was named Rice’s first vice president of innovation, a position created by President DesRoches. The mission of the new office is to translate breakthrough discoveries into inventions for societal benefit, with the primary areas of focus currently being energy and health. While Cherukuri is new to this role, he is neither a stranger to Rice nor to Houston. His long association with the Texas Medical Center and stints at Rice — as a Ph.D. student, researcher and executive director of the Institute of Biosciences and Bioengineering — are integral to his unique experiences and enthusiasm for raising Rice’s profile in the innovation ecosystem. “We’re going to make mind-blowing inventions that help people live better, healthier lives. It’s beyond a privilege to do this,” he said. We recently sat down with Cherukuri to learn more about the path that led him to this role.

An immigrant childhood leads to Houston …

I was born in India, and my family came [to the U.S.] when I was about a year old. We — my mother, Suseelamma; father, Theodore; and my older brother, Thomas — landed in New York City, as many of us did back in the 1970s — because there was a physician and nursing shortage. I grew up in a thriving community in Brooklyn where physicians and nurses who came over from India worked, and “aunties” took care of each other’s kids. My younger brother, Peter, was born in New York.

When my father got a fellowship to train under Denton Cooley as a heart surgeon at the Texas Heart Institute, we came here to Houston. I was about 7 or 8 years old. Sometimes, my father would take us to see open heart surgeries and animal experiments related to artificial hearts, using mechanical pumps they were putting in cows. I loved seeing that!

… and then to West Virginia

Because my father grew up in a very tiny village in India, he wanted to serve people in an underprivileged community in America. We moved to an Appalachian town on the border of West Virginia and Kentucky. Even though I didn’t have access to good math and science classes in the hills, I loved to build things and tinker. I was very fortunate that my parents tolerated my insanity growing up because I would try to build some really crazy tech. One of these things was a rocket belt, like the one James Bond flew in “Thunderball.”

Medical school with a side of entrepreneurship

When it was time to go to college, I enrolled at the University of Kentucky to study physics — I wanted to earn a Ph.D. eventually, but my parents wanted me to go to med school. “You’re Indian, you need a good job, go to med school,” they said. I went to med school in Trinidad but still did research every summer with my undergraduate mentor at UK. We were working on a technology to monitor glucose for diabetes patients using a kind of watch device that was way ahead of its time.

Looking back a decade from now, I’d like the world to see just how special Rice University really is by the people we’ve taught and the new ideas and technology we’ve made.

An unexpected return to Houston

Texas Heart got wind of our work and its relation to cardiovascular disease and asked me to attend a medical meeting in Washington, D.C., to meet with cardiologist Jim Willerson [also president of the University of Texas Health Science Center of Houston]. At the meeting, Dr. Willerson invited me to come to Houston to start a company, but I wanted to finish medical school, so I turned down his offer. The meeting was on Sept. 11, 2001. I drove past the Pentagon still smoldering from the attack. A few days later, Texas Heart called me again to come work on a DOD project for trauma relief, and I really wanted to help our military, so I said yes and hit pause on medical school.

‘Be a real doctor.’

Shortly after I arrived in Houston, Willerson introduced me to Rick Smalley. He was a brilliant thinker and tech entrepreneur. Finally found someone that really got me. I planned on transferring to UT Health to finish med school but then Smalley said, ‘You know, Paul, why don’t you quit medical school and be a real doctor?’ Smalley said that if I joined his lab, he’d make the group half biotech and half nanotech. I just couldn’t refuse his offer, so I quit med school and became his student. Smalley took a chance on me, but sadly, it was only about a year and a half that I was officially his student, before he died of cancer in 2005. But he totally changed my life for the better.

Forming an unbreakable bond

I graduated under Bruce Weisman, my final thesis adviser, and another wonderful mentor. It was also in Weisman’s lab that I met my wife, Tonya, and she’s also a physical chemist and scary smart. She’s the vice president of a company that spun out of Rice called Applied NanoFluorescence, which designs and manufactures spectrometers. We have two children, Adam, 12, and John, 9. Our wedding reception was held on campus at the RMC. Jim Tour, another mentor at Rice, presided over the ceremony. I thought it would be really cool to have a chemist help form an unbreakable bond. We even had a nanotube-shaped cake, and all the tables were numbered after fundamental particles in physics. We really nerded out.

From Tennessee to Texas

We lived in Chattanooga for a while, both working at a pharmaceutical company called Chattem to quickly launch a nonprescription version of Allegra. But we missed Houston and ended up moving back when Jim Tour invited me back to Rice to help manage his lab, and in exchange I could do my own research in my spare time. Anybody who didn’t love Rice would think that was a crazy move, but I loved it. From there, I was asked to be the director of the Institute of Biosciences and Bioengineering (IBB). In understanding what the IBB was, I thought about something Smalley told me years ago, which was that because the departments are small at Rice, the way you maximize their magnitude was to bring faculty together to solve problems through the institutes. So, I asked: What were the problems in the biological and bioengineering spaces that we could work on, and what resources did faculty need to do that?

Looking back a decade from now, I’d like the world to see just how special Rice University really is by the people we’ve taught and the new ideas and technology we’ve made.

What is innovation?

Innovation has always been part of Rice’s research and educational enterprise, but what Reggie wanted to do in creating this office was amplify innovation in all its forms. Innovation is at the heart of what Rice does through the scholarly works of our faculty and students — books, music, art, research and inventions.

Looking back a decade from now, I’d like the world to see just how special Rice University really is by the people we’ve taught and the new ideas and technology we’ve made. So, a big part of my mission is to provide the support for our faculty and students to develop and even commercialize their innovative discoveries for the betterment of our world.

Interview by Lynn Gosnell | Illustrations by Katie Mulligan