Remembering Robert Curl

Bob Curl, a chemist, nanotech pioneer and alumnus, was a beloved faculty member for 64 years.

Nobel Prize-winning chemist Robert Curl, an internationally acclaimed scientist and nanotechnology pioneer whose 64-year career at Rice University made him one of the institution’s most beloved and respected figures, died July 3 in Houston at 88.

Curl, University Professor Emeritus and the Kenneth S. Pitzer-Schlumberger Professor Emeritus of Chemistry, spent most of his life at Rice. He earned a bachelor’s degree in chemistry from what was then the Rice Institute in 1954 and returned as an assistant professor in 1958 after his Ph.D. studies at the University of California, Berkeley and a brief postdoctoral stint at Harvard.

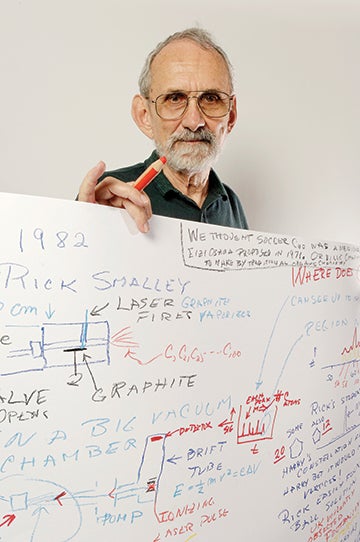

Curl was a physical chemist who used lasers, microwave radiation and other tools to study the structure of molecules and how they react. He, Rice’s late Richard Smalley and Britain’s Harold Kroto shared the 1996 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for the discovery of carbon-60, or “buckminsterfullerene,” a closed cage structure of 60 carbon atoms in the form of a soccer ball measuring about 1 billionth of a meter, or a nanometer, in diameter.

“The ‘buckyball’ discovery laid the foundation for Rice’s current leadership role in materials research,” said Tom Killian, dean of Rice’s Wiess School of Natural Sciences. “This fundamental research established a new field of organic chemistry and provided key inspiration for the ensuing rapid growth in the study of nanoparticles and nanomaterials and the emergence of nanotechnology.”

He was an extraordinary colleague, and despite his talent and his acclaim with the Nobel Prize, he was unfailingly modest and generous to other people with his time and attention. I think of him as the soul of our department. He made everybody around him better.

While in an undergraduate chemistry course, Curl learned about Kenneth Pitzer’s discovery of barriers to internal rotation about single bonds and decided to go to the University of California, Berkeley to work with Pitzer. Pitzer, who would become Rice’s third president in 1961, was Curl’s Ph.D. adviser and helped him get a postdoctoral position studying microwave spectroscopy with E. Bright Wilson at Harvard in 1957. Curl continued his studies after he was recruited to Rice as an assistant professor the following year. He would go on to spend most of his career studying the spectra, structures and kinetics of free radicals and other substances via spectroscopy.

“He would never have called himself a nanotechnologist,” said James Heath ’88, president of the Institute for Systems Biology in Seattle and the principal graduate student involved with the buckyball discovery.

“You’ve got physical chemistry, where people work on various levels of quantitation,” Heath said. “And then you’ve got spectroscopy, which is the most quantitative aspect of physical chemistry. And that is really what Bob loved.”

Despite retiring in 2012, Curl continued to work and was regularly seen on campus. Rice chemist Bruce Weisman described Curl as a constant presence at seminars through the most recent semester. “It’s really remarkable because these are not big events, with famous people speaking,” Weisman said. “These are part of our graduate program where students get to talk about their research, mostly to other students. Bob, despite having been retired for a long time and having no obligation to do this, would come just to satisfy his curiosity about what was going on, and also help the students.

“He was an extraordinary colleague, and despite his talent and his acclaim with the Nobel Prize, he was unfailingly modest and generous to other people with his time and attention,” Weisman said. “I think of him as the soul of our department. He made everybody around him better.”

— Jade Boyd