A Found History

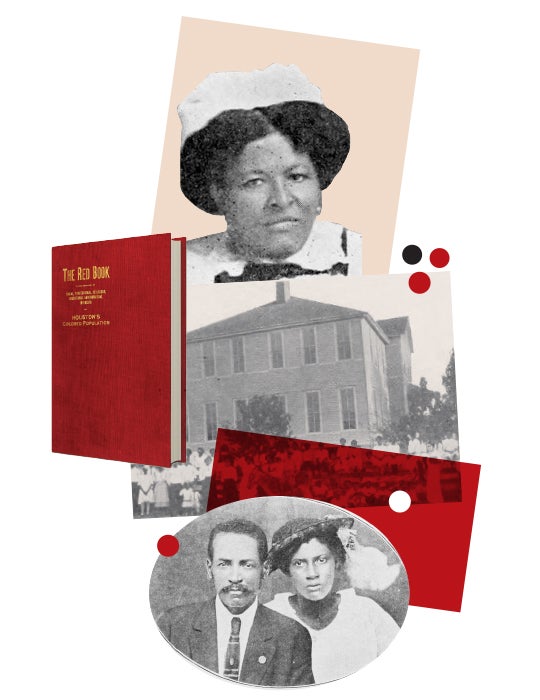

Student-driven research into the rare and remarkable “The Red Book of Houston” reveals new details about Houston’s thriving Black citizens in the early 20th century.

By Katharine Shilcutt | Photo illustrations by Alese Pickering

Now in her first year of medical school at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, Susanna Yau ’20 credits an unexpected research project during her senior year as a history major with transforming the way she’s approaching her future career as a physician.

Yau is far from the first person who’s come away changed by their encounter with “The Red Book of Houston” — and she won’t be the last, now that the rare book’s abundance of spatial data has been preserved for public research at Fondren Library’s Woodson Research Center.

There’s no book like it in any other American city, from any other time period. “The Red Book of Houston: A Compendium of Social, Professional, Religious, Educational and Industrial Interests of Houston’s Colored Population” — published just once, in 1915 — offers a detailed depiction of Black middle- and upper-class life in the Bayou City at a time of both triumph and trial.

‘The Red Book of Houston: A Compendium of Social, Professional, Religious, Educational and Industrial Interests of Houston’s Colored Population’ — published just once, in 1915 — offers a detailed depiction of Black middle- and upper-class life in the Bayou City at a time of both triumph and trial.

“We could find nothing comparable to it anywhere,” said Norie Guthrie, an archivist and special collections librarian in the Woodson. “The Red Book” is recognized by researchers as unique in its comprehensive and creative celebration of Black life over a century ago, published 50 years after the Emancipation Proclamation declared “that all persons held as slaves” were freed.

Guthrie spearheaded a yearslong project to digitize and promote its contents by making it accessible to researchers in digital formats, including a story map built with historic maps of Houston and spatial data painstakingly gathered from the pages of the century-old book.

During the undertaking, Guthrie partnered with a team of Rice students, including Rachael Pasierowska, who earned her Ph.D. in history in 2021; Ryan Chow ’21, an English major; Tanvi Jadhav ’21, who majored in history with minors in sociology and politics, law and social thought; and Yau, whose own work on the project revolved around retrieving and cleaning up data on the many schoolteachers listed in “The Red Book,” including their home addresses.

A REVEALING ARTIFACT

“It’s such an amazing treasure,” said Guthrie, who was looking for a new topic for a Woodson Research Center blog post when she stumbled upon a copy of “The Red Book” in Rice’s archives in early 2019 and vaguely recalled a conversation she’d once had about a similar-sounding red book with Reginald Moore, the late Sugar Land activist and historian whose own files also reside at the Woodson.

“When I saw it, I thought of Mr. Moore,” said Guthrie, who immediately recognized the treasure trove of data presented in its pages. “I opened it and was like, ‘What the holy …’”

The book itself is so rare that the Woodson only owns a photocopy, though a high-resolution version is available online. A handful of original copies reside locally at the Houston Metropolitan Research Center and the library at Texas Southern University (TSU).

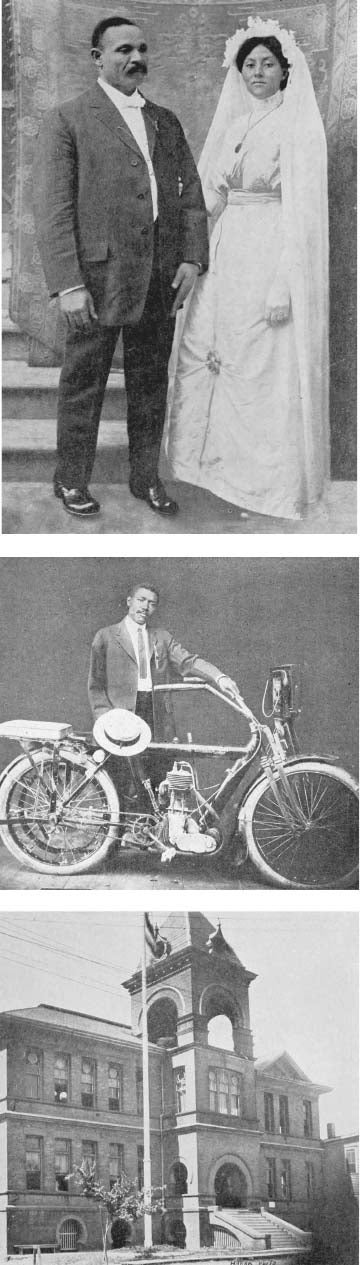

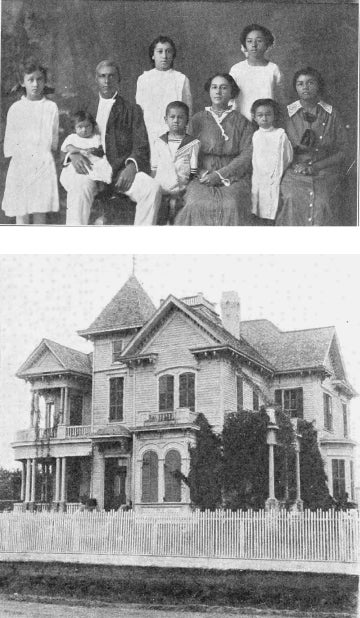

Originally printed on glossy stock, the book showcases the personal and professional lives of the city’s most prominent Black citizens: bankers and businessmen, preachers and schoolteachers, their extensive educational backgrounds enumerated and their portraits taken in front of their churches or homes. A wedding photograph of James Pendleton and Lillie Bell Price Pendleton notes their ceremony “was among the most important that Houston has produced, being attended by white and colored en masse.”

“It was a very powerful statement for them to make this book,” Guthrie said. “The Red Book” teems with photos, essays, poetry, histories and business directories, boasting hundreds of local listings for everything from physicians and attorneys to ice cream parlors and picture shows.

Originally printed on glossy stock, the book showcases the personal and professional lives of the city’s most prominent Black citizens: bankers and businessmen, preachers and schoolteachers, their extensive educational backgrounds enumerated and their portraits taken in front of their churches or homes.

C.G. Harris, the official photographer of “The Red Book,” with his traveling portrait studio: a camera mounted to a bicycle.

Colored High School at 3030 San Felipe Road is one of several schools listed in the book.

With the help of a Fondren Fellows grant, Guthrie and her team kicked off a data retrieval and cleaning project in 2019, resulting in over 900 names and addresses extracted from “The Red Book” during their ambitious undertaking. Fondren has made this work available online for free in the form of geospatial mapping data. Future researchers can use this wealth of data to continue exploring “The Red Book” with geographic information system software and other tools.

The data Guthrie and her team pulled is already being put to use on projects like “Black Life in Houston: An Atlas of Racial Inequity, Displacement, and Integration” from Farès el-Dahdah, a professor of art history and humanities. Jadhav assisted on that project by tracing the 90-plus churches listed in “The Red Book,” using Houston city directories and other Fondren resources to confirm and flesh out the data before pulling it into the atlas.

“You can see the expansion of the Black community in Houston through the construction of churches,” said Jadhav, currently a Venture for America fellow. Working on the project provided an opportunity for humanities research during her senior year, said Jadhav, but it also gave her a greater understanding of the history of Houston’s Black community and its impact on the development of neighborhoods such as the Third Ward and Freedmen’s Town.

“I think this project helped me to recognize the impact that locations of community, such as religious buildings, can have on the character of a neighborhood,” Jadhav said. “It also made me rethink what empty lots and new construction are: a reflection of how a city has changed and the different stakeholders and communities that are prioritized.”

A WINDOW INTO HOUSTON’S PAST

“What’s really cool about ‘The Red Book’ is that it has allowed undergraduates to get involved in these research projects and to learn more about the city where they’re going to school,” said associate dean of humanities and history professor Fay Yarbrough ’97, who assisted Guthrie with convening an online panel last spring that debuted the project’s story map to the public, with hundreds in (virtual) attendance.

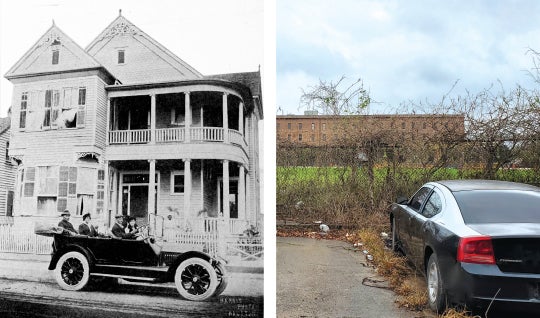

Familiar Houston wards once filled with thriving Black schools, churches, businesses, lodges and homes came to life during the panel as Guthrie scrolled through a series of maps. It ended with a poignant selection of shots showing the current state of a few of these Houstonians’ homes: vacant lots, towering overpasses.

Also on that panel were TSU professor Cary Wintz ’65, who discussed the history of the Fourth Ward; fellow TSU professor Karen Kossie-Chernyshev ’85, who covered African American history in Houston City Council’s District B; and Bernadette Pruitt, associate professor of history at Sam Houston State University, who used “The Red Book” in her own scholarship and talked about African American migration patterns to Houston.

Questions about these patterns and more came in throughout the discussion (which is available for viewing on YouTube). There was even some speculation about Houston’s own Harlem Renaissance and whether or not “The Red Book” may be able to shed more light on Black culture in the Bayou City in the years leading up to the 1930s. “I think the idea of a Houston Renaissance is intriguing to folks,” Yarbrough said.

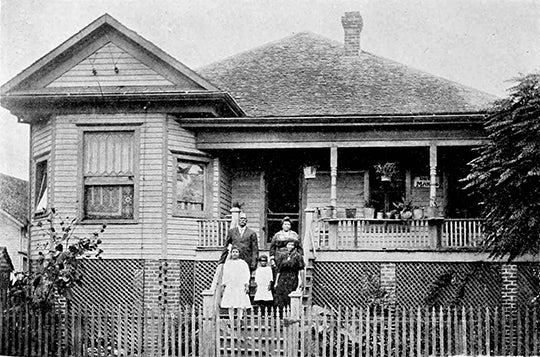

One of those who migrated to Houston around that time was a midwife named Annie Hagen, who “came to Houston with 50 cents and through her industry and thrift … accumulated a nice bit of property” around the turn of the 20th century. Photographs taken in 1915 depict two of those properties, with a proud Hagen standing alongside her family on the front porch of their home at 609 Hobson St.

Hagen’s neighborhood was later demolished to make way for Interstate 45 and Allen Parkway. Hobson Street no longer exists, one of many parts of Black Houston carved away over the years.

Just as homes and churches depicted in “The Red Book” have been lost to time, so have the names of those responsible for creating the book and the motives they held for its publication — an expensive endeavor that cost $80 per copy in today’s currency. The publisher printed nothing else before or since. And though a second edition seems to have been planned, it never came to fruition.

These are just a few of the mysteries presented by “The Red Book,” which Guthrie hopes can be investigated using the data she and her team have collected.

A THRIVING BLACK COMMUNITY

“The Red Book” was published on the cusp of America’s Great Migration, during which 6 million African Americans left Southern states and headed to the north and west. Houston in 1915, ever on the leading edge of demographic change, had already experienced its own surge, however; its Black population tripled every decade between 1860 and 1890. By 1910, census data showed nearly 24,000 Black residents, comprising 30% of the city’s total population.

Meanwhile, a new wave of Jim Crow laws had been enacted in Houston: Streetcars became segregated in 1903, followed by hotels, restaurants, movie theaters and other public places in 1911. The 1910 Slocum massacre weighed on local minds: Dozens of African Americans were slaughtered in an unincorporated town 150 miles north of Houston, but a grand jury empaneled in Harris County declined to indict any of the killers. The contemporary “Blue Book” society directories of Houston and Galveston listed only white people and businesses.

But Houston’s Black community was thriving, especially in areas like Independence Heights, which became the first African American municipality in Texas in January 1915. And “The Red Book” proudly displayed this fact for all to see.

“Part of its purpose is to push against the ideas that white people might have about what Black people are capable of, of what they had achieved — just every kind of stereotype,” Yarbrough said. “I see it as this really clear statement: ‘Look, this is what we are. You can think whatever, but we have proof. This is what we are.’”

All those who read “The Red Book” are inspired by a different facet of its carefully curated account of Black life in Houston over 100 years ago.

For some, it’s the intimate portraits and photographs taken by C.G. Harris, the official photographer of “The Red Book,” shown on one black-and-white plate with his traveling portrait studio: a camera mounted to a sturdy-looking bicycle. For others, it’s the lists of businesses that clearly delineate a thriving community filled with barbershops and banks, dentists and dressmakers.

The Broyles family residence on San Felipe Road

AN INFORMED CAREER PATH

For her part, Yau was intrigued by the schoolteachers. In 2019, she was assisting Alexander Byrd ’90, vice provost for diversity, equity and inclusion and associate professor of history, with a research project on whether or not teachers at three different schools in the Houston Independent School District actually lived in the neighborhoods where they taught. Studies have shown that both teachers and students benefit from having teachers live in the areas they serve, but stagnant wages and increasing home prices have made this inaccessible for many teachers across the country.

Yau joined “The Red Book” team when Byrd suggested working with them to find data she could use to study historic teacher residence patterns in Houston.

“The work I did with Dr. Byrd and ‘The Red Book’ team provided a perspective on Houston and education that I never would have thought about otherwise,” Yau said. “I cannot say enough about how valuable my history background and history research experiences in particular have informed my understanding of the cities where I live and my career.”

After graduating from Rice, Yau was inspired to take a gap year and work through AmeriCorps at a nonprofit in Houston’s historic Fifth Ward. Yau said that her work with “The Red Book” project helped her make sense of the complex social issues she encountered during her AmeriCorps term and has continued to propel her on a path of public service.

“Seeing how deep-set structural racism in America has been and continues to be, through both my history classes at Rice and my research into 1918 and 2019 Houston public schoolteachers, has motivated me to pursue a career in medicine to serve marginalized communities,” Yau said. Now in medical school, Yau reflects on her undergraduate career and the humanities research she accomplished as totally transformative.

“One of the reasons I chose to come to Baltimore was the University of Maryland’s emphasis on serving the community, and already I have seen many parallels between the social inequality in Houston and in Baltimore,” Yau said. “Because it so deeply affects individual stories and experiences, I know that having intimate knowledge of the history of the inequality I am seeing today will allow me to one day better serve my patients as a physician.”

All images in this story are from “The Red Book of Houston” and are in the public domain.

demolished, such as 2121 German St., pictured here.