Love & Law

Charles Spain’s election to the 14th Court of Appeals caps a legal career centered on civil rights for all.

By Deborah Lynn Blumberg

It was summer 1986 in Waco, Texas, when Charles Spain ’81 walked into the family law class he was taking at Baylor University, fuming.

Earlier that morning, the U.S. Supreme Court had announced its decision in Bowers v. Hardwick, a case in which an Atlanta resident arrested in his home for sodomy sued Georgia’s attorney general, claiming the state’s sodomy statute violated its constitution. At the time, sodomy was a felony under Georgia law. The Supreme Court upheld Georgia’s state law by a vote of 5–4.

Spain remembers saying to his classmates, “I just want to tell everyone that the U.S. Supreme Court has handed down one of the worst decisions in the entire history of the court.” At the time, it was a brave statement for Spain, who hadn’t come out to his classmates, his professors or even his parents. In 1973, Texas had made “homosexual conduct” a criminal act, though a Class C misdemeanor. It wasn’t until 2003 that the U.S. Supreme Court struck down the Texas state law criminalizing homosexual sex between consenting adults.

That summer, Spain got angry. He was angry about the Supreme Court decision and angry that during the AIDS epidemic, it felt taboo to talk about the disease. Organizing AIDS education at Baylor was unthinkable, he says. When finding himself at such crossroads, he’s learned to ask himself, “What are you going to do about it?”

Spain chose to become an advocate for civil rights, and he’s carried that conviction with him throughout his career. His accomplishments include co-founding the first LGBT section of a state bar in the nation and working on the national level to end the Boy Scouts’ ban on gay Scouts and leaders. He was also instrumental in getting the Confederate battle flag removed from the reverse of the Texas state seal.

NEW TO THE BENCH

January marks Spain’s first full year as an elected judge on the 14th Court of Appeals, which covers 10 counties in Southeast Texas, including Harris County. He serves along with seven other justices and a chief justice on the court, which decides on civil and criminal appeals from lower courts across Texas. In a given week, he might decide on an appeal in something as consequential as a murder case or as mundane as a contract dispute. The Court of Appeals is the last stop before a case potentially goes to the state’s two highest courts — the Supreme Court of Texas, which hears civil cases, and the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals.

“Our job is to answer the question that people bring to us,” he says. “It’s not to fix things. Sometimes at the end of a case, there’s no happiness to be had.” For example, in cases involving custody decisions, “no one’s empowering you to go back with a magic wand and make a happy family.”

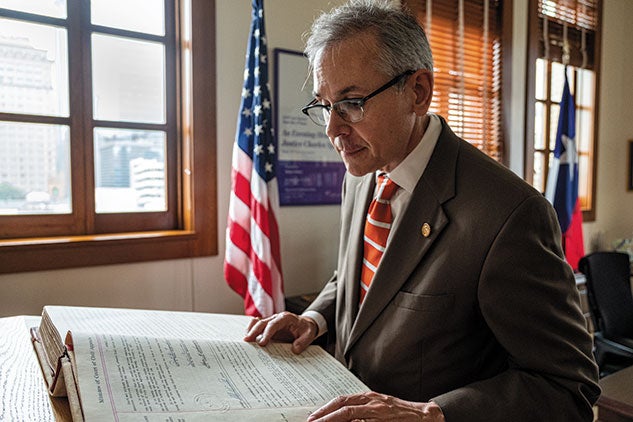

Each week, Spain pores through reams of documents and typically votes on an average of six appeals. He shares the responsibility of writing the court’s opinions with his peers. Unlike the fast-paced work of a staff attorney or his prior role as a municipal court judge, Spain often has the luxury of time to think and talk deeply about the law. Because of this municipal court experience, he has “a far deeper sense of how the law affects people.”

“It’s a privilege,” he says about his current role.

A DEDICATION TO SCOUTING

One of the most profound influences on Spain’s life is Scouting, which he credits for teaching character development, citizenship training, physical and mental fitness, and leadership. Spain continued to be active in the Boy Scouts after he became an Eagle Scout, the Boy Scouts’ highest achievement, at the young age of 14. (Fun fact: On his computer, Spain stores a scan of the congratulatory note he received from President Richard Nixon — a formality that any Eagle Scout can request from a current president, by the way.)

Spain is married to civil appeals attorney John Adcock, and they have a teenage son, Jeff, who is also an Eagle Scout. Spain worked to get the Boy Scouts to drop its ban on gay Scouts in 2013 and welcome gay leaders in 2015. He and Adcock became the first openly gay Scout leaders in the Sam Houston Area Council. On Sundays, when the family is not at St. Stephen’s Episcopal Church, chances are they’re camping with their Scout troop — perhaps in Spain’s beloved Piney Woods in East Texas.

“My son has been the troop chaplain aide for the past four years, and I’ve helped put together the morning prayer Sunday services during the troop campouts,” Spain adds.

He continues to build upon decades of fond Scouting memories. Two years ago, Spain, his son and six other members of Palmer Memorial Episcopal Church’s Troop 511 backpacked 30 miles in the Great Smoky Mountains. This past summer at his son’s Eagle Scout court of honor, Eagle Scout Phyllis Frye, the first transgender judge in the United States, gave his son the traditional Eagle Scout charge.

CIVIL RIGHTS AND THE STUDY OF FLAGS

Becoming an attorney was not one of Spain’s early career ambitions. He thought he would follow in his father’s footsteps, a radiologist and Rice graduate from the Class of 1950. But Spain’s heart wasn’t in medicine. At Rice, he majored in history and eventually decided to go to law school. Today he quips, “Law is the last refuge for humanities majors who want to eat.”

At Baylor, he started to confide in others about his sexuality. He linked up with people in the Waco Lambda Student Association, the first LGBT college student group in town, of which he was a founder. The group distributed fliers to churches, letting members know they were there for support.

Around the same time, Spain met with plaintiffs and lawyers in a separate court case, Baker v. Wade, a civil lawsuit in Dallas challenging the “homosexual conduct” statute. He wanted to learn more about how they had built their case. “I started to network,” Spain says. “By the time I graduated, the civil rights bug had bit.”

When Spain graduated from Baylor, he had six months before starting a judicial clerkship at the Supreme Court of Texas. He took a temporary law firm job in Houston and lingered in its library to avoid rush hour traffic. It was from there that his passion for vexillology, or the study of flags, took off. (In fact, Spain’s interest in flags started early — his grandparents flew the “Six Flags Over Texas” at their café in Crockett.) He started researching the laws around Texas’ first national flag. He wrote to Whitney Smith, author of “The Flag Book of the United States,” outlining why Smith was wrong about who created the first national flag of Texas and who designed the Lone Star Flag. “I thought he’d tell me to go to hell,” Spain says.

But Smith wrote him back, excited to have learned something new. That inspired Spain to continue studying vexillology. Ultimately, Spain’s research led to a new Texas law in 1993 that revised the laws related to the Texas flag and amended the state flag code. Part of the amendment included standardizing flag colors.

From his research, Spain believed the hues of red and blue in Texas’ flag were originally meant to match those of the U.S. flag. So, he drafted an act to specify that. His friend, then-Rep. Leticia Van de Putte, filed the bill; the legislature passed it; and the governor signed it. “That color blue on the Texas flag, that’s because of me,” Spain says. “If you want something done, do it yourself.” In his courthouse office, Spain’s desk is flanked by the Texas and U.S. flags. Now, Spain serves as one of the three directors of The Flag Research Center, originally founded by Smith.

Spain worked as a briefing attorney for the Supreme Court of Texas and as a staff attorney for the 3rd Court of Appeals in Austin and the 1st District Court of Appeals in Houston. He’s also held attorney positions at top law firms. Once, Spain asked his supervisor, the chief justice of the 1st Court of Appeals, for permission to join a gay lawyer’s group. The judge said yes and gently scolded him for asking. “I never again asked for permission,” he says.

NEVER GIVE UP

On a recent Wednesday in a courtroom in the Harris County Courthouse, Spain points to an engraved Texas seal affixed to the front of the bench. Two branches surround a single white star. He runs a finger along the branch on the left side of the seal.

“It’s post oak, but it should be live oak,” he says. “I can’t fix everything.” But he’ll try. Recently, Spain wrote about Texas and the LGBT community in The Houston Lawyer magazine. While the Supreme Court struck down the Texas state law criminalizing homosexual sex between consenting adults in 2003, the Texas Legislature has yet to repeal the unconstitutional “homosexual conduct” statute, Spain notes in the magazine. In the words of Winston Churchill, Spain wrote, “Never give up.” If you want to make something happen, he says, “show up, say something, do something.”