Antarctic Journal

During an eventful and demanding research expedition to Antarctica’s Thwaites Glacier, science writer and photographer Linda Welzenbach chronicled the crew’s progress and daily challenges aboard ship and on icy shores.

Story and photos by Linda Welzenbach

Antarctica’s Thwaites Glacier is enormous, remote, starkly beautiful — and a focal point for global sea level rise predictions. Since 2018, under the auspices of the International Thwaites Glacier Collaboration, eight scientific teams from around the world have been investigating the glacier and its adjacent ocean environment. The massive research project is funded by the U.S. National Science Foundation and the United Kingdom’s Natural Environment Research Council through 2023. The ultimate goal is to collect data that helps scientists and policymakers to understand the past, present and future of glacial melt contribution to sea level rise.

Though much has changed for Antarctic explorers in the century since Roald Amundsen and Robert Falcon Scott raced to the South Pole, scientific research on the continent remains a grueling and painstaking process. But the rewards are many, says Linda Welzenbach, the science communications specialist in Rice’s Department of Earth, Environmental and Planetary Sciences. Last January, during the waning days of the Antarctic summer, Welzenbach embarked on the collaboration’s first cruise as part of THOR, short for Thwaites Glacier Offshore Research.

A geologist by training and a veteran of two previous Antarctic research trips, Welzenbach served as THOR’s public outreach coordinator, a role that drew on her scientific training as well as her considerable writing and photography skills. Via blog posts, Welzenbach documented the scientific, technological and human aspects of research under extreme conditions. From this unique perch, she also captured moments of sublime beauty at sea and across forbidding landscapes. Welzenbach drew from THOR’s expedition blog and trove of photos to share her journey with Rice Magazine readers.

JAN. 28

After 24 hours of travel from Houston to Punta Arenas, Chile, I arrived exhausted yet excited — and perhaps just a wee bit anxious of the unknown — to be part of something unique. My role on this expedition is to share the scientific discoveries that will come from our journey to Antarctica on board the icebreaker and research vessel Nathaniel B. Palmer. Akin to a spacecraft exploring new frontiers beyond Earth, the ship and her marine operations specialists will navigate safe passage through Antarctica’s icy waters for the next two months. In addition to the nine geologists (including me) assigned to the THOR project, there were two other scientific teams aboard the ship, as well as technical support contractors, the ship’s captain and operating crew, cooks and media personnel. All in all, 58 people, including 22 scientists, would be calling this ship home for the next two months.

Owls were well represented on the THOR team — Julia Wellner ’01 is one of two principal investigators. John Anderson, the W. Maurice Ewing Professor Emeritus of Oceanography, serves as a co-investigator. While neither Wellner nor Anderson accompanied this cruise, Becky Totten Minzoni ’14 was on hand to study the offshore seafloor environment and the historical behavior of tidewater glaciers as a result of climate change.

JAN. 31–FEB. 4

With last-minute maintenance accomplished, we are on our journey to the Amundsen Sea and ultimately the Thwaites Glacier, expecting to arrive in seven to 10 days. As we pass through the Straits of Magellan, the seas are already rough with the swells striking the Palmer broadside of the beam. In the early afternoon of Feb. 4, the swells regularly exceed 20 feet. Sea legs nearly acquired, the roll, pitch and yaw still cause a nagging fatigue. By midday, I try to take a nap. Within minutes of hitting my bunk, the port to starboard roll became progressively more pronounced, and at 1:40 p.m. culminated in what became known as “The Big Tilt.” Our cabin door, facing the port side, became a near-horizontal floor. All our “secured” gear tumbled down a 45-degree incline to the door, my head saved from smacking the bulkhead by my pillow. Miraculously, no one was hurt.

Here's video from of the bow of the Palmer during the ship’s rough passage through the Straits of Magellan.

FEB. 5

For four days, we endured extremely rough seas, deep gray skies and rain as we passed through the South Pacific Ocean. A red glow leaking through my curtains drives me out of my bunk. It’s then that I notice the calmer seas. We have finally sailed beyond the bad weather. My cabinmate, Becky Totten Minzoni, who’s also taken to her bunk during this passage, groggily encourages me to go up to the bridge and “see what there is to see.” Clearing skies, at last! The sun was setting — a sight we could still enjoy before the days got increasingly longer.

The next day, we saw our first iceberg, and soon after, we crossed the Antarctic Circle — a momentous feeling.

FEB. 9

The sound of ice breaking is as unnerving as it is loud. Ice complains, but yields against the 1 9/16-inch metal hull. On the early morning of Feb. 9, the Palmer’s progress was finally halted by the several-feet-thick pack ice. It was time to turn on all four engines. Nothing short of rock could now stop 6,800 long tons (that’s about 15 million pounds) of ship with thousands of steel plates carrying almost 425,000 gallons of gas.

The Palmer, technically a research vessel and an icebreaker, makes its way through the semifrozen Amundsen Sea. A time-lapse video shows the ship’s determined progress.

FEB. 10–12

The days’ science activities include sampling the seawater and collecting a core of the seafloor in Ferraro Bay. This is a shakedown activity for all of us newbies. Then we are full steam toward the Edwards and Schaefer Islands, where our two other science teams will be deployed to sample ancient shorelines and to tag seals. The rest of us are left to take in the sound and the overwhelming smell — a combination of wet dog, ammonia and rotten fish — of Adélie penguins going about the business of raising their young and preparing for the winter ahead. We would spend the next couple days at these islands, many of which have never been touched by humans.

Antarctica is the only breeding habitat for large colonies of Adélie penguins. Welzenbach observed Adélie penguin parents “running in all directions away from their tenacious chicks who are begging for another snack.”

FEB. 12

Seal tagging is not what it sounds like, nor is it a straightforward business. Seal tagging can be called science rodeo — the seal wins the Stetson, but one in the form of a small computer that collects data for the next year. Timing and skill are important.

For the Antarctic seals, it’s about the timing of the fur molt and the scientist’s skill with the animals to ensure that they are well cared for and unharmed by the process. Seals molt at the end of the Antarctic summer each year, so the computer needs to be attached to new fur. For the following year seals go about the business of living, none the wiser about the science they are conducting. These science partners go to places and to depths humans cannot, continuously gathering data, most importantly during the dead of winter. The following summer, when the seal molts again, its rodeo prize falls harmlessly away. As of the end of June, the 11 tagged seals (over the entire cruise) logged more than 3,000 temperature and salinity profiles during roughly 45,000 dives.

FEB. 14–18

When we enter the Amundsen Sea Embayment, we’re just a day away from our main destination, the Thwaites Glacier — but then, the unexpected happens. Someone is very sick, and the Palmer is already making a U-turn to head north toward the closest port for transport to Chile. At the Palmer’s maximum speed of 13 knots, the British Antarctic Survey’s Rothera Research Station on the Antarctic Peninsula is four days away. While everyone is concerned with the well-being of the person who is ill, there is an equal and palpable concern about how the team will accomplish all our goals in 10 fewer days. The scientists, used to overcoming adversity, are already working on adjustments and contingencies. The time would be used to best effort — cleaning data, refining laboratory processes, and establishing collaborations and friendships. There would be more time to observe all the different types of ice, spot whales and seals, and in my case, catch up on blog writing!

FEB. 19

Becky wakes me about two hours before my shift, apologizing, but assuring me that it’s worth the sleep deprivation to see the sun dawning over the mountains that line both sides of Marguerite Bay. Mountains rise straight out of the water of the bay, snow-like smoke whispering away from the highest peaks and edges. The mountains are packed with streams of ice, sinuous with hints of blue bending through their valleys. The terminating glaciers are cracked and crevassed where they make their way over the final bedrock hurdle into the sea.

FEB. 19–21

Rothera Research Station is situated on Adelaide Island. Within minutes of reaching anchorage, a small boat launches from Rothera Point to collect our medical emergency. Now we wait anxiously for the plane’s return with a replacement technician, the mood anticipatory of the immediate departure back to the Amundsen Sea. But it is not to be. The weather in Chile would delay the flight for two days! So plans are made to go ashore again. At Rothera Station, our time is filled with media interviews, station tours, accessing mail — and stocking up on chocolate bars. The following afternoon, our new technician is delivered and we are off, speeding back to the Amundsen Sea. The lesson that was brought home is that the safety of our crew is paramount.

FEB. 26

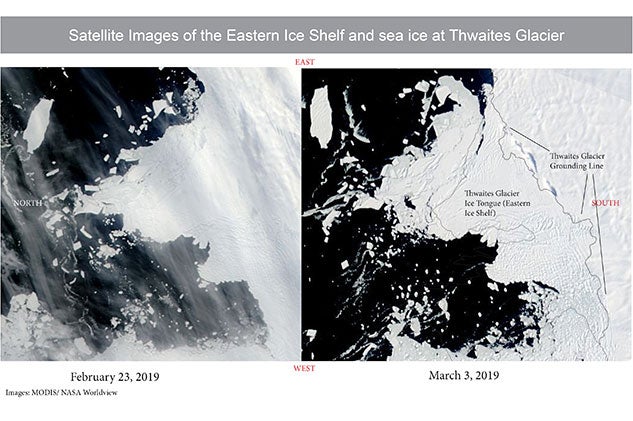

The day dawns a deep blue gray, but eerily calm — a perfect backdrop for the towering 30- to 40-meter wall of the eastern ice tongue of our destination, the Thwaites Glacier. Its crystalline face was fractured, glowing deep teal to cobalt in the fissures and cavities. The Palmer glides slowly, 400 meters from the face of the ice shelf. There was a silent reverence among us all when the glacier finally came into view — and gratitude that the way was not blocked by ice. The Palmer’s previous trip to the Thwaites was in 2000; in 2006, another ship surveyed the area. Neither mission made it farther south of 74 degrees, 50 minutes latitude. On this mission, the Palmer sailed along a new ice-free boundary that is 18 kilometers farther south than in 2006. This is a strong indicator that “climate forcing” is contributing to ice shelf retreat. Scientists have been able to see via satellite rapid changes in ice shelf behavior.

The ice shelf extends about 15 kilometers beyond the grounding line. The grounding line is where the glacier transitions from resting on the bedrock to a floating ice shelf in the Amundsen Sea. Along the 150-kilometer ice front, satellite images show two different types of ice shelves. The eastern ice shelf looks like a large solid piece of ice. Moving west along the front, the ice changes into what looks like alligator skin. That texture is created by crevassing of the ice as it moves past the grounding line. Once they move into the sea, the ice eventually breaks along the fracture lines.

FEB. 28

Sleep deprivation is the No. 1 problem for the THOR crew of scientists, who operate on 12-hour shifts, leaving only a few hours to sleep, exercise or “see the sights” — that is, the world going on outside and around the ship. Since I’m a working scientist as well as a science communicator, my noon to midnight shift is taken up partly with monitoring the sonar mapping process of the seafloor (and below the seafloor). One thing I’m looking for is potential coring sites. Collecting seafloor sediment cores is one of our missions — these samples are key to understanding the Thwaites Glacier’s historical behavior. When not processing cores, I write my blog, go to the bridge, and take photos or process images.

MARCH 3

By now, the THOR team has surveyed more than 1,500 square kilometers of new seafloor in the Amundsen Sea Embayment in front of the Thwaites Glacier. During this time, we are all business with little time for sightseeing. I note areas on the seafloor that look like good targets to core. We collected 14 cores from six sites. The Kasten corer is the workhorse of seafloor sampling. Its 12-inch square metal barrel can capture up to 9 feet of sediment. With its 15-ton weight on top, it is sent to the seafloor like a straw into a large bowl of pudding, but at speeds of up to 30 meters per second. A fully loaded Kasten core can weigh up to 1,000 pounds, so the entire team is needed to deadlift it onto a cart on deck and roll it into the lab.

MARCH 7–13

On March 7, we wake early to find ourselves gone from Thwaites. The Palmer is sitting quietly in the ice-free waters of western Pine Island Bay. When we arrive at Pine Island Glacier, we find the calving front has retreated several kilometers since the last survey in 2017, providing the opportunity to survey newly exposed seafloor. While we are there, we receive satellite imagery of ice movement, a near-daily part of traverse planning. New images show a sudden breakup and dispersal of the far western alligatored edge of the Thwaites ice tongue. Not only was it concerning to everyone on board, but it meant that the conditions around us were beginning to deteriorate. Going back to Thwaites was no longer an option.

About the same time, we received word that we would be granted three extra days to conduct science, so back to the Edwards and Schaefer Islands we would go to collect one more core from an area that hadn’t been sampled in decades. Despite the mayhem behind us, the sea near the islands was a mirror, bringing the sky to the ground, yet allowing us to peer tens of meters below the water’s surface.

MARCH 14–17

The bridge at night is very quiet, almost cathedral-like in the darkness. I like to end my day there, letting the fatigue and stress of getting so much done in so little time float away with the view. But tonight it is surreal, the ship is a bright orange island surrounded by solid sea ice. Blowing snow caught by the searchlights used to find iceberg obstacles makes it feel as if we are sailing through space.

MARCH 18–22

The day before the Palmer commits to crossing Drake Passage is bittersweet. The sea is full of brash ice, bringing to mind stories of Ernest Shackleton and the Endurance, but with the comfort of knowing that the Palmer will never get stuck. Southern fur seals are seen swimming among the floes throughout the day, as are many whales. Flocks of petrels and albatross hover around the ship. The marine biologists on the teams think that there is some kind of nutrient upwelling attracting all the wildlife, which also include crabeater seals. Despite the engaging sights, there is a disquiet in the back of our minds. The Palmer is less much of the fuel that would have added ballast to our trip across the passage. The Palmer skirts ahead of a massive cyclone that produced an amazing tailwind, like a giant hand pushing us to speeds of up to 17 knots.

MARCH 24

In contrast to the loud and halting push through ice, the Palmer’s slide into the dock at Punta Arenas was smooth as silk. The only sounds marking our arrival were the raucous cries of seagulls. Everyone was up on the top deck, marveling at the sights and smells of civilization, each of us silently recognizing that something special was over. The lack of pitch, roll and yaw signaled that we not only had arrived, but that the next steps to understand the glacier we left behind would have to be taken back home.