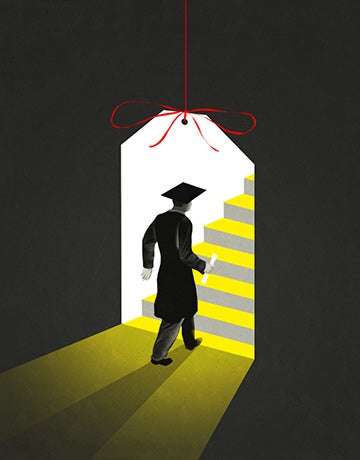

A Bold Step

The Rice Investment builds on the legacy of Rice’s founding vision.

When Lorena Gauthereau graduated from Rice in 2004, she headed off into the world armed with a bachelor’s degree in English and political science, but she and her parents were saddled with thousands of dollars in student debt.

As a teenager, Gauthereau remembers her Mexican-immigrant parents being adamant about her and her two siblings going to college, even as they struggled to get by on her father’s modest salary from his work as a lab technologist at the only hospital in town. Gauthereau, who grew up in Eagle Pass, Texas, a small city nestled alongside the Rio Grande, was able to attend Rice because of a generous package of financial aid, but it didn’t cover the full costs of college — or off-campus learning and service trips. So she and her parents took out loans. Then, when Lorena’s siblings enrolled in college, the Gauthereaus borrowed even more.

“It was a huge financial burden for my parents to send me and my siblings to college,” says Gauthereau, who eventually earned her Ph.D. at Rice and is now a Chicano literary studies scholar at the University of Houston. “We’re still paying back the loans.” When she learned that there’s now help for Rice students just like her through The Rice Investment, Gauthereau was overjoyed.

Rice’s ambitious new initiative — announced in September — dramatically expands financial aid for incoming and current undergraduate students. It’s part of a larger strategic plan to make a Rice education more accessible and affordable, and it’s at the forefront of other colleges and universities across the country that are unveiling similar efforts. Many of these efforts alleviate costs for lower-income families. Rice’s plan provides targeted and generous support to the middle class as well. It’s a segment of society that’s been left in financial aid limbo — with too much income to qualify for aid, but not wealthy enough to afford tuition at a top-rated higher education institution without loans or sacrifices.

The contours of The Rice Investment are particularly straightforward. Undergraduate students with a family income between $65,000 and $130,000 get full tuition scholarships at Rice. Those with a family income below $65,000 receive aid covering full tuition, room and board, plus other fees. And students with family income between $130,000 and $200,000 receive grants covering at least 50 percent of tuition. Families must have what Rice is calling “typical assets” — in other words, assets that are not above what’s typical for their income level.

Beginning in the next academic year, degree-seeking undergraduate students from families with incomes up to $200,000 who qualify for The Rice Investment will no longer be required to take out loans as part of their need-based financial aid packages. Instead, loans will be replaced by scholarships and grants.

There’s no cap on the number of students who can apply. The program will be funded by a special distribution from Rice’s endowment but will be made permanent by a fundraising effort that seeks to raise $150 million for financial aid endowments.

Over the years, Rice has steadily improved its financial aid support and is well-known for its “need-blind” admissions policy — meaning qualified applicants may be admitted regardless of their family’s ability to pay for college. With 38 percent of Rice undergraduates receiving some kind of need-based assistance, the average financial aid award totaled $40,285 last year. Beginning in 2008, Rice instituted changes to address the growing issue of student loan debt. Freshmen with family incomes below $80,000 were not required to take out loans as part of their financial aid package. Rice also started limiting federal loan debt for other students to $10,000 over four years. Such financial aid policies factor into a consistent history of high rankings by college guidebooks, such as the U.S. News & World Report’s “Best Colleges” guidebook, where a key measure is a university’s financial resources. Last year, Rice ranked No. 16 among national universities.

In announcing expanded aid, Rice President David Leebron said, “Talent deserves opportunity. We’ve built on our already generous financial aid to provide more support to lower-income and middle-class families and ensure that these students have access to the best in private higher education.”

Prompted in part by alumni concerns about rising tuition, administrators first started mulling over what more they could do several years ago. College tuition had been rising steadily over the last few decades. In the meantime, student debt had skyrocketed from about $600 billion 10 years ago to today’s more than $1.5 trillion held by over 44 million Americans, according to the Federal Reserve.

“With concerns about middle-income families and the squeeze they’re feeling, we felt we could do more,” says Vice President for Enrollment Yvonne Romero Da Silva, who joined Rice in 2017. Families shouldn’t have to struggle with saving for retirement or covering health care bills while also trying to educate their children, she adds.

Almost immediately, the response was overwhelming. Alumni and high school counselors alike have lauded the initiative, Romero Da Silva says, and excitement from students at high school college fairs has been palpable. Both early decision and regular applications to Rice are up as well, and alumni have already contributed almost a third of the $150 million goal to support the program.

“It’s really hit a chord,” she says. “Hands down, this is one of the greatest initiatives I’ve had a chance to be a part of.”

Susan Rexford, director of college guidance at the Charles E. Smith Jewish Day School in Rockville, Md., has been tracking Rice’s financial aid policy for her students. “The one thing you always look for is the asterisk,” she says. “What are the conditions? And Rice’s conditions are pretty straightforward. Rice has always been a generous school. This is going to make it even more attractive.”

For her part, Gauthereau has started touting Rice’s virtues to her 7-year-old son, Travis, even though he’s still in grade school.

Building on a Legacy

The Rice Investment builds off Rice’s founding tradition of not charging tuition. It was not until 1965 that Rice students started paying tuition, the result of a lengthy legal process that sought two major changes in the university’s founding charter from 1891 — not only seeking to charge tuition, but also ending a shameful policy of segregation, opening Rice admissions to all students based on merit.

Association of Rice Alumni (ARA) President-elect Frank Jones ’63 benefited during Rice’s tuition-free days, as did his mother, Grace Griffith Jones ’38, brother Donald Jones ’66 and three of his uncles. Frank, who’s been watching college tuition costs soar, has poured money into college savings accounts for his grandchildren. He’s proud of Rice for investing in a larger swath of students.

“I think it’s wonderful,” he says. “We’ve been missing out on a group of students who are very qualified, but whose parents just don’t have the wherewithal to pay the tuition.”

At KIPP Houston High School in Alief, Texas, college transition adviser Jennifer Dewhirst says that four times as many seniors applied to Rice in 2018 after the tuition announcement compared to 2017. “There was definitely a ripple of interest as application season started,” Dewhirst says. “Having Rice do something like this so close to home is a game changer for many Houston families who don’t want their children to go far away for college,” she adds. “It’ll push students to choose Rice over other schools.”

At KIPP, where 80 percent of students qualify for a free or reduced lunch, many students receive aid, but there are still gaps to fill and loans are often the only answer. “We have alums in their 30s with well-paying jobs who’ve moved back in with their parents,” says Dewhirst. “They’re struggling with crippling student debt.” Recently, one KIPP Houston High School student enrolled in a two-year community college rather than the four-year college she was accepted to because her parents wouldn’t let her go into debt to cover costs. “Her parents freaked out,” Dewhirst says.

They’re not alone. Nearly three in five people believe “affordability of a college education” is a “very big” national problem, a jump of around 11 percent from 2016, according to the Pew Research Center. The issue of affordability is something countless current and former Rice students have experienced first-hand. “[The Rice Investment] is really important for lower-income students, a category I was in when I went to Rice,” says Matt Haynie ’03, a former ARA president. “Rice made it possible for me to attend. Now, with increases in tuition across the higher education landscape, I think universities have to do more to make it accessible. I think it’s going to make a big difference in attracting talent.”

From the mid-1980s to the 2015–2016 school year, college tuition rose more than twice the rate of inflation. Gradually, the possibility of going into debt became one of the biggest factors keeping students from applying to top private universities. “This new generation is more conscious than ever of student debt,” says Martin Van Der Werf, associate director for editorial and postsecondary policy at the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce. “They’re trying to avoid it.”

Institutions nationwide are tuned into these fears, and they’ve responded. Top national universities like Harvard, Princeton and Stanford have all retooled their financial aid policies with an eye toward access and affordability. Recently, prestigious public universities like the University of Virginia, the University of North Carolina and The University of Texas all announced generous new financial aid policies for students from both low-income and middle-income families. Dartmouth and Amherst College recently announced expanded scholarship aid as well.

“This [expanded income-based financial aid] is something we’re seeing more and more of,” says Van Der Werf, “and it certainly helps from a competitive standpoint.”

The initiative will help current students like Alaina Bertram ’21 and her twin brother, Emmett ’21, the children of a public high school math teacher and a stay-at-home mom who are from Tomball, Texas. For the Bertrams, affordability was the biggest factor when deciding on a college. “We never had that much money,” Alaina says. Both she and Emmett applied early to Rice and received aid. Without it, she adds, they wouldn’t have been able to enroll at all. Even so, the Bertrams were looking at the likelihood of additional loans. “I thought I’d have to pull out tens of thousands of dollars in loans. But with The Rice Investment, I may not have to take out any.”

Increased Interest

Ariana Engles ’20, president of the Student Association, has spoken extensively with fellow students and student leaders about the initiative. “It’s a wonderful move forward for low-income and middle-income students, one that will help generations to come and put Rice in the forefront of people’s minds,” says Engles. As a middle-income student, Engles says that having the investment when she applied to college would have made her feel more secure in her decision to apply to Rice.

Engles, however, echoes a sentiment expressed by many students who hoped the initiative would also apply to international students. It doesn’t, in part because what’s classified as a middle-class salary in the U.S. may well translate into an upper-class salary in another country, says Romero Da Silva. “It’s important to continue with the mindset of making Rice accessible for all students,” Engles says. International students, however, can still receive need-based financial aid.

At The Kinkaid School in Houston, senior Dani Knobloch had been fretting about financing her college education ever since her parents divorced in 2016 and she and her mother moved into a friend’s house. “I didn’t know if my dad would be paying anything,” she says. The Rice Investment made her feel confident about applying early, a decision she’d been wavering on. With the money saved, “we’d be able to get our own place and save up a little more,” Knobloch says.

Quenby Mott, the head upper school dean at Kinkaid, values Rice’s focus on the middle class, an important group to have on campus to bridge the gap between lower-income and more affluent students. She also values Rice’s transparency. “That makes it so much more powerful than a lot of other highly selective institutions’ efforts,” she says. More Kinkaid students now see Rice as a viable opportunity, Mott adds.

Romero Da Silva hopes the initiative will prompt additional institutions to follow suit in offering more robust aid to students. “I’m hoping we lead the way and shift the conversation about financial aid.”