Syllabus: Medieval Guts and Glory

Anatomy of a Rice Class

Winter 2017

By Jennifer Latson

HIST 211: Medieval Violence (Fall 2016)

Department: History

Description: Students develop a critical approach to the study of violence and its function and cultural significance within medieval European society. In particular, they explore why medieval people legitimized certain kinds of violence while condemning violent acts that deviated from social norms.

Between the beheadings, the mutilations and the catapulted corpses, the conversation in Maya Soifer Irish’s Medieval Violence class could be mistaken for a “Game of Thrones” recap. But while Irish, an assistant professor of history, is grateful to the HBO series for helping make this a golden age for medieval studies, all the brutality and barbarism is just an entryway to the course’s real focus: the concentration of power in medieval society, where elaborate rules of chivalry empowered an elite group of nobles. “Violence is a window into the Middle Ages,” Irish explained. “Warfare and violence always reflect the society in which they take place.”

How knights end up in hot water

Medieval violence was highly circumscribed by the rules of chivalry. “You don’t strike an opponent who’s lying on the ground … You treat your opponents with respect. You don’t betray your lord,” Irish explained. “What I want my students to realize is that medieval violence is not some free-for-all where anyone can kill anyone, which is an idea we get from shows like ‘Game of Thrones.’” For one thing, knights were expected to only pick on people their own rank. Violence against the lower classes could be punished harshly, as a 12th-century count demonstrated when he boiled a knight alive in his full armor for stealing two cows from a peasant.

When Got Your Nose goes too far

For a research project, freshman Nikhil Chellam studied Byzantium, the Roman Empire’s Eastern successor state, where nobles had a nasty habit of mutilating their rivals, often by slicing off their noses or ears. This practice, uncommon in Europe, ensured that an opponent could never become emperor, since Byzantines viewed physical flaws as outward manifestations of character defects. “It’s a uniquely Byzantine concept: as God’s representative on earth, you have to be physically perfect,” Chellam explained. “Any change in your outward appearance mirrors a change in your inner persona, so mutilating someone branded them as a sinful person.” One emperor bucked the trend: Justinian II, nicknamed “the Rhinotmetos,” meaning slit-nosed. After he was deposed and his nose was cut off, he returned with a solid gold prosthetic and a legion of mercenaries to retake the throne.

It’s raining heads

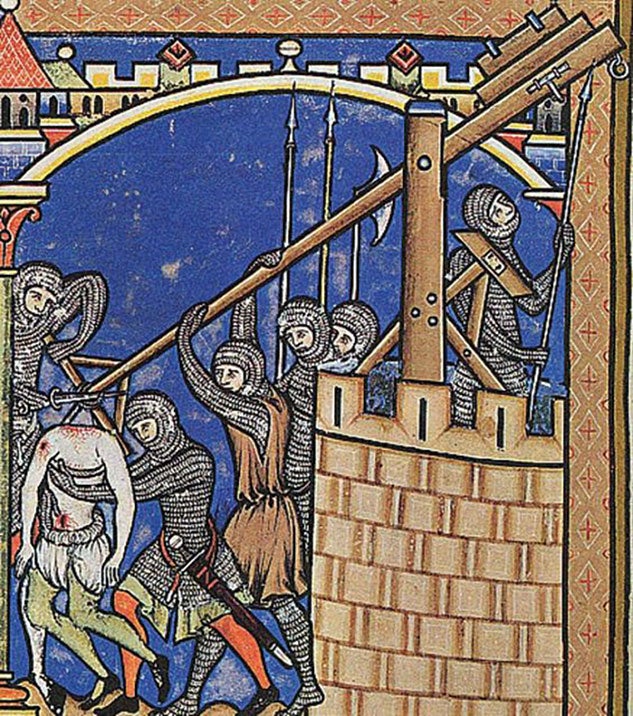

Walker Grimes, a sophomore majoring in mechanical engineering, did his research project on the evolution of siege weapons and constructed a working model of a trebuchet, or medieval catapult. Because there were no standing armies during the Middle Ages, it was nearly impossible to assemble enough soldiers to overpower a castle or fortified city, so invaders had to wait until the people inside ran out of food and supplies. Siege weapons like the trebuchet were a way to hurry things up. The trebuchet could lob rocks large enough to make a castle wall crumble; failing that, it could send a fireball over the ramparts. Invaders were creative in their choice of projectiles. “They would throw trash, severed heads, animal corpses and human corpses, including the bodies of bubonic plague victims,” Grimes said. “They wanted to spread disease, break morale and generally make the city a really unpleasant place to be.”

The more things change …

Was medieval society more violent than the world is today? “My students quickly figured out that we have just as much violence: it’s just a different kind of violence,” Irish said. Some historians have even run the numbers, comparing the violent crime rate in medieval England (made possible thanks to meticulous record keeping there) to that of modern cities. “For a city like Chicago, it’s comparable,” Irish said.