Now Reading: Alumni Books

A picture history of chemistry; Black life and police violence; and philosophy in the films of Terrence Malick

Summer 2023

By Hilary C. Ritz

O Mg!

How Chemistry Came to Be

Stephen M. Cohen ’89, ’92

World Scientific Press

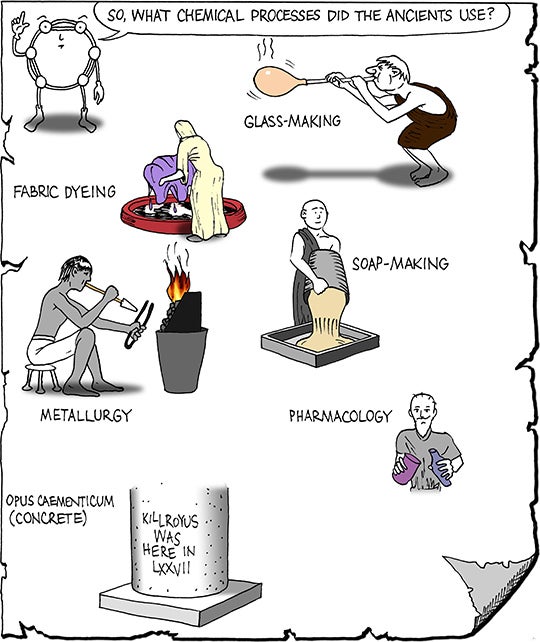

A lively, colorful graphic novel for teens and laypeople, “O Mg! How Chemistry Came to Be” is a fascinating, enthusiastic and humorous presentation of the history of chemistry from Greek times well into the 2000s. The book keeps readers engaged by including historical context from art, language, literature, politics, music and more — plus a few “Easter eggs” and plenty of dad jokes.

Author Stephen M. Cohen might be uniquely qualified for this project, as he holds a doctorate in chemistry from Rice and has also been drawing cartoons since boyhood, including a comic strip in the Daily Pennsylvanian while an undergraduate at the University of Pennsylvania. He also hosts a weekly podcast called “The History of Chemistry.”

How difficult was it to draw a history of chemistry?

Very, [especially] in regards to making it look historically accurate. For example, the photographs tended to be black and white in those days: 19th century. So, I had to research, if somebody was wearing a cravat and a jacket, what color might that be? If women were doing research — and pictures of women in the labs are more difficult to find — what would they have worn? If they spoke, I wanted to include one or two words of their native language, and I happen to like languages, but I don’t know every language. There was also the apparatus to draw, so I’d have to go back into the literature and look for what that apparatus actually looked like. And then of course there’s the topic itself. How do I draw a particular experiment? How do I draw a chemical topic? How do I draw molecules moving around?

All the research that you did makes the book tremendous fun to look at, because there are so many interesting details to notice on every page.

Yes, that was deliberate. In some cases, I put in Easter eggs, as some people call them. I put in a few dad jokes; I’m a dad, so I get to do that. Humor is a way to relax people and get people more interested in the topic of chemistry and science. People think about chemistry classes and they freeze up: “Oh my god, it’s gonna talk about moles and balancing equations.” I really don’t do that in the book. I don’t think I even mentioned the word mole, deliberately.

On a serious note, you’ve said that Isaac Asimov didn’t talk about chemical warfare in his history of chemistry published in the 1960s, and you decided to do the opposite. Tell me about that decision.

When Asimov wrote his book, chemistry was sort of — if you can imagine a 1950s newsreel narrator — the world of progress! So, he was really doing it from that perspective, that nothing will stop science — it’s upward and onward forever. But I wanted my book to say chemistry has found all kinds of wonderful things, but put it in the wrong hands, then bad things happen. Even good people with good intentions can unintentionally do bad things. I had to talk about Fritz Haber [and chlorine gas]. I had to talk about Louis Fieser and napalm. You have to talk about these things. You can’t ignore them. In this world of censoring in schools of topics that you don’t like, we have to talk about all of chemistry and all of history and then be the judge after that.

You made a point of including women scientists who’d been previously overlooked. Tell me about Stefanie Horovitz and how she’d been virtually unknown until she was covered by Chemistry World in 2020.

[When I read the Chemistry World article,] I had to rewrite a chapter and add an entire extra page about her because I thought her work was so important. Then it was reported that she was killed by the Nazis in Treblinka. [I searched] the Yad Vashem website, which is the central history collector for the Holocaust in Israel, and yes, a relative had submitted a page of testimony about her. So I wrote to Yad Vashem asking permission to use it. It’s just something that no one hears about, but she discovered that isotopes are real: It’s one of the most important discoveries of the 20th century.

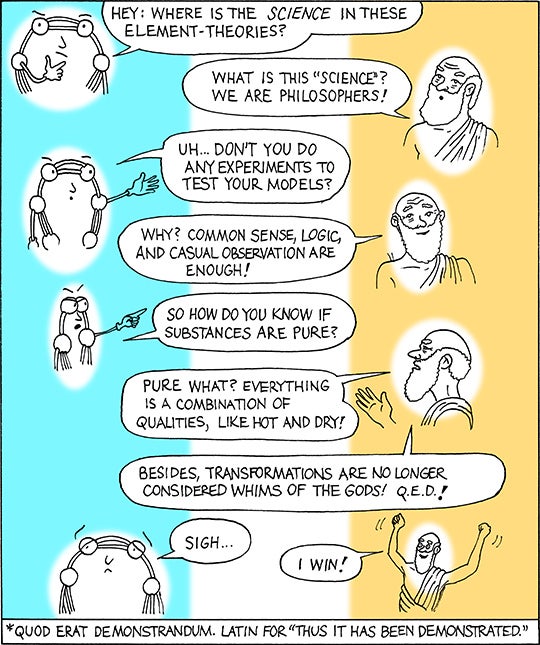

We have two guides ushering us through the book: Ben Zene is on almost every page, and Democritos shows up very early and then comes back as a recurring character. Tell us more about them.

Ben Zene is an old chemical joke. There are a bunch of these sorts of jokes, things that have gone around for decades, if not hundreds of years, and Ben Zene is certainly one of them. I used Ben Zene as sort of this guide but also a foil, in a way. And then Democritos, he came up with the idea of atoms. Back then, the Greek philosophers just said stuff, and some of it was right and some of it wasn’t, and he happened to randomly say the right thing at the right time. But I brought him back [repeatedly] as sort of the crazy uncle. “Look, I can’t believe they really found atoms. I can’t believe it. Oh my god, but it’s quantum. Light is atoms, but it’s a wave. Ah, I’m freaking out!”

What’s your favorite anecdote about the writing process?

There was one Swedish chemist, Scheele, of the 18th century who didn’t get his stuff published, and I wanted him to say something like “darn it” in Swedish. So I was texting [my niece in Stockholm], and she kept giving me all these vulgar words which I can’t use, because this is a book for teens and I don’t want parents coming after me with pitchforks and torches for corrupting their fine young innocent minds, but it turns out most languages are a lot more vulgar than English. So finally she came up with this: She said in the Pippi Longstocking books, Pippi says “Fy bubblan!”: “Oh, bubbles!” And I said, I can use that!

What do you want people to take away from reading the book?

This book is for everybody to appreciate that chemistry — and science in general, but chemistry in particular — has evolved in time, that what you see in a chemistry book is the end product of hundreds, if not thousands, of years of research. Chemistry is an evolving science like all other sciences; it’s not fixed in time.

Black Life Matter

Blackness, Religion, and the Subject

Biko Mandela Gray ’17

Duke University Press, 2022

In his introduction, Biko Mandela Gray describes his approach in “Black Life Matter” as a “sitting with” the deaths of four Black Americans who suffered violence at the hands of police officers. “The dead still speak,” he says, “and we can hear them if we only listen.” One comes away from the book convinced he has done just that. His study of the deaths of Aiyana Stanley-Jones, Tamir Rice, Alton Sterling and Sandra Bland is profound, visceral and meaningful — unrelentingly attentive, but never exploitive.

An assistant professor of religion at Syracuse University, Gray was trained as a philosopher of religion, and “Black Life Matter” examines how theodicy, ontotheology and interpellation play out in anti-Black police violence. “My goal in this text,” he said in a recent interview with the Black Agenda Report, “was to show how the phrase ‘all cops aren’t bad’ is a form of religious apologetics. ... The goal ... is to push toward other ethical frames that might afford different possibilities.”

What shines through the philosophy is Gray’s commitment to “take care” with the lives he writes about. That care is always present on the page. “Do not mistake my claims or my intentions,” he cautions in the conclusion. “Love and care do not erase or escape the violence. But they are ways that we live in the midst of such violence.”

Life Above the Clouds

Philosophy in the Films of Terrence Malick

Edited by Steven DeLay ’13

State University of New York Press, 2023

American director Terrence Malick studied philosophy at Harvard and Oxford and taught philosophy at MIT, as well as published a translation of Martin Heidegger, one of the most influential philosophers of the 20th century. But in 1969 he set aside his academic career to express his views through film instead. And what films: His works are described in this anthology in such effusive terms as “invitations to receive the gift of this world” (Page 253), “stunningly beautiful” (Page 25) and “they make God perceptible” (Page 12).

Editor Steven DeLay, research fellow at the Global Center for Advanced Studies, describes himself as “at the moment probably the most prolific phenomenological philosopher working in the world in English.” This, his sixth book-length project, was lauded by editor of Place Images in Media Leo Zonn as an “exceptionally rich, creative and intriguing study of Malick and his imprint on the world of filmmaking.” Fans of Malick’s work will return to their beloved films with fresh insights; those unfamiliar will feel inspired to discover this remarkable filmmaker for the first time.