Living Voyages

A massive digital resource on the Atlantic and inter-American slave trade finds a home-base at Rice and leads to new discoveries about the history of slavery in Texas.

By Laura Furr Mericas | Illustration by Katy LeMay

In a South Carolina classroom in summer 2018, a group of high schoolers enrolled in a college access program settle into their desks. Nafees Khan, a professor in Clemson University’s College of Education, is presenting on America’s slave trade. It’s a subject they’ve learned about before, but today’s lesson will take on a new tone.

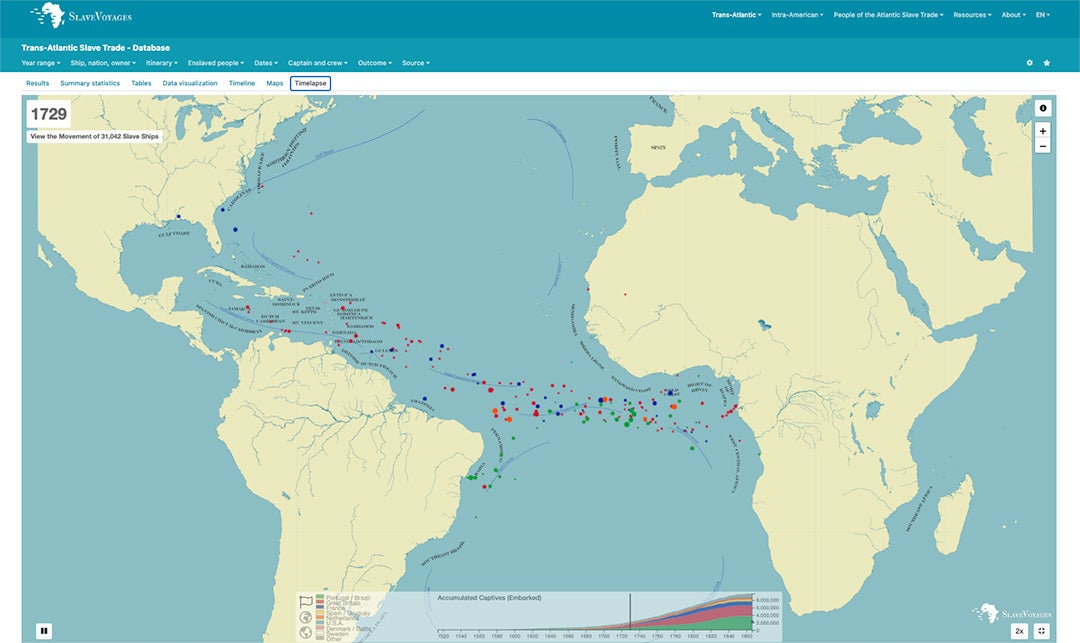

Khan, the curriculum director for SlaveVoyages, flips on a video — a two-minute time-lapse of the 350-year history of the trans-Atlantic slave trade that brought 12.5 million enslaved Africans by force to the Americas. Built with data from SlaveVoyages, the world’s largest repository of information about the slave trade across the Atlantic and within the Americas, the video displays tiny dots moving off the coast of Africa toward the Caribbean, Brazil and North America across a blue and yellow map. Each dot represents a voyage of enslaved people.

Starting in the year 1520, a few tiny dots flow out from the coast of Africa each second. As time inches toward the 18th century and the height of the trade, more dots than the eye can count speed across the ocean — their size (representative of the number of enslaved individuals onboard) consistently growing, many heading directly toward the students’ home state.

Khan watches as the students furrow their brows. Some speak out in anger. Others sit in silence, brooding as they begin to make connections. These are the moments when the power of SlaveVoyages can really be felt, he says. “There’s a realization that those dots are representing hundreds, if not over 1,000, people,” Khan recalls. “And kind of that moment of going from watching a visualization to realizing that those are lives. Those are people.”

Striking interactives like this one — first created by the news site Slate before a similar version was developed internally by the SlaveVoyages team — are just one of the ways the collaborative database of voyage records has been put to use over the lifetime of the project. Khan and his team have spent the better part of 15 years developing lesson plans and resources that educators can use to teach from the data. Scholars around the world have relied on the database for research on topics ranging from genetics to economics. And anyone with internet access can use the platform to take their own deep dives into their ancestry.

But the overarching takeaway, Khan says, is the intentionality that the database presents — one that speaks to the global enterprise that was the slave trade. More often than not, the data leaves users asking, “How did I not know this before?”

“[The slave trade] wasn’t just happenstance — it was actually intentional actions,” Khan says. “The database offers context and evidence that is oftentimes thought to be not available, but it is quite available.”

An Organic Archive

What’s known today as SlaveVoyages got its start in the 1960s when historians like the late Philip Curtin at Johns Hopkins University began to code archival data of ship manifests into machine-readable formats, like punch cards and floppy disks.

A few decades later, Emory University historian David Eltis built upon Curtin’s work, releasing what was known as the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database via CD-ROM. For Eltis and Curtin, the primary goal was to answer fundamental quantitative questions about the slave trade — and this continues to be a driving goal of SlaveVoyages today.

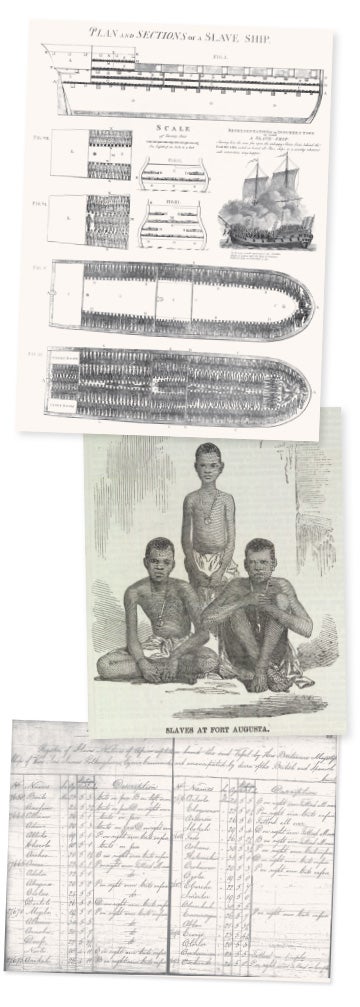

Regardless of its format, over the years the database has helped reveal information about the Middle Passage for users and has provided answers about the number of slave ships that made the voyage across the Atlantic, the survival rate, the male-to-female ratio on board individual ships, when insurrections occurred and much more.

The database has been continuously updated by researchers around the world with thousands upon thousands of data points — including information on more than 36,000 voyages and the names of those on board (though very few of the enslaved individuals’ names have survived for inclusion) — and continues to be revolutionary for its ability to look at the slave trade from a global perspective.

Daniel Domingues da Silva, an associate professor of African history at Rice, describes it as an “organic database.” In this sense, “it is always changing, growing,” says Domingues, who has contributed decades of research to the database. “We can add new information about voyages that we already documented [or information about] new voyages, and we can correct any mistakes in the available records.”

A close secondary goal has always been to make this information accessible. “Everybody who’s been involved with this project feels the responsibility of maintaining it and making it available to the public,” Domingues says. “One pressing concern is [how] to avoid becoming obsolete.”

Domingues joined Eltis at Emory by way of Brazil in the early 2000s as a researcher around the time the team was transitioning the database from a $199 CD-ROM to a freely accessible website, which launched in 2008 as SlaveVoyages.org.

Much like the data, the website itself has been updated several times to become more user-friendly and to offer more entry points for users, with time-lapse video and 3D models. Soon, researchers will add “Echoes: The Slave Voyages Blog” along with more qualitative information to the site, says Domingues, who continues to oversee the project.

Thanks to grants totaling $150,000 from the National Endowment for the Humanities and £250,000 from the Arts and Humanities Research Council of the United Kingdom, Rice, in partnership with the U.K.’s Lancaster University, will be linking digital records on SlaveVoyages.org to images of the centuries-old documents from which that information was first derived.

The grants will support the digitization of a batch of account books, correspondence, manifests and other documents, dating from the 1720s to the 1740s, from one of the largest British carriers of enslaved Africans, the South Sea Company. The three-year project will serve as a “pilot,” Domingues says. If all goes well, it will become the structure for uploading more document images from more libraries around the world.

“By having the images in this new repository, we will give the public direct access to the documents,” Domingues says. Still, according to him, now that the database is all on the web, the priority of accessibility has taken a back seat to one of sustainability. And, in many ways, this is what led SlaveVoyages to its current home.

A New Consortium

In March 2021, Rice officially became the host of SlaveVoyages.org, meaning that the university has direct access to the database and is responsible for maintaining it after nearly 20 years at Emory. The School of Humanities and Fondren Library today serve as its co-hosts, with support from the Center for Research Computing (CRC).

Additionally, in 2021, Rice and Emory launched a consortium with four other institutions — the Hutchins Center for African and African American Research at Harvard University, the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, the Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture at William & Mary, and three University of California campuses (Berkeley, Irvine and Santa Cruz) — to ensure SlaveVoyages’ maintenance and longevity through long-term funding and direction.

“It’s leading SlaveVoyages to a new phase of its history,” Domingues says. The consortium allows the partners to rely on each other for advice and technical support and to lean on each institution’s expertise in new ways, he explains. Academics like Domingues have contributed years’ worth of research, while others, like those at the National Museum of African American History and Culture, are experts at exhibiting that information in impactful ways.

“They give a lot of critical feedback on how to [promote] our project to an entirely new audience,” Domingues says. “It’s very beneficial in that sense and also creates a basis for how to keep the project moving forward.”

Earlier this year, the University of the West Indies at Cave Hill, Barbados, joined the consortium, making it the first international institution to be part of the SlaveVoyages project and one from a country that shares a significant history in the slave trade. The university’s additions to the database will come from the newly formed republic’s “Reclaiming Our Atlantic Destiny” initiative. The information will confirm and add to records for countless voyages in the Caribbean and is a “huge contribution,” according to Domingues.

“It was important for them and it is important for us to have this support and recognition of our project by a Black majority country undergoing an important moment in their history,” Domingues says.

Washington University in St. Louis is slated to join the consortium in July, and the SlaveVoyages team hopes to add more international partners from key locations, such as South America and Africa, in future years to continue to push the project forward.

With the added technical power, SlaveVoyages is primed for the future. In addition to launching the consortium, Domingues and his team have migrated SlaveVoyages to the cloud with the help of Oracle Cloud Infrastructure and Rice’s CRC. In addition to bolstering the platform’s safekeeping, the CRC team says the move to the cloud will allow the database more flexibility and room for expansion to accommodate new research — including research that hits close to home for Rice.

Filling in the Blanks

Around the time that SlaveVoyages made the jump from Atlanta to Houston in 2021, undergraduate history students uncovered a surprising realization: Texas was largely absent from the database.

“We had always used the SlaveVoyages website. It was such an important source of information,” says history major Victoria Zabarte ’22. “I was looking at it, and I realized that even though I knew we had a very large slave presence in Texas, there were no voyages that were going to Texas.”

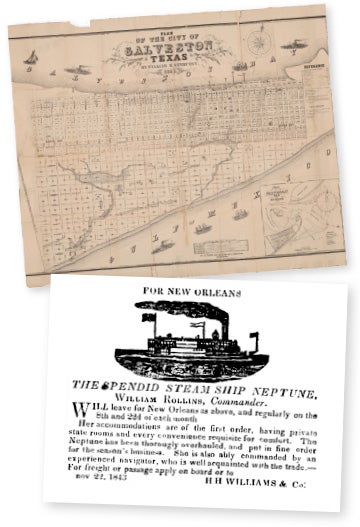

With advisement from Domingues and Rice lecturer Molly Morgan, Zabarte and fellow history students Katelyn Landry ’22 and Ben Schachter ’22 teamed up to look at slave voyages along the Gulf Coast. Prior to this fresh look, historians largely believed that manifests containing information about these voyages coming into Texas had been destroyed in the 1900 hurricane that devastated Galveston.

While it is true that the inward manifests collected at the Port of Galveston were destroyed, documents from the port of embarkation (known as outward manifests) still existed.

“It was just taking [something] that people had thought of as fact — ‘These records just don’t exist’ — and thinking, ‘Well, maybe they do exist, but in a different place,’” Zabarte says. “And in fact, they did. And they were publicly available this whole time on the National Archives website and on Ancestry.com. But no one really thought, ‘Maybe these actually should be researched and analyzed.’”

The results were eye-opening. The team identified and compiled about 3,000 copies of outward manifests originally issued for voyages from New Orleans, Mobile and Savannah heading to Texas, which led to 15,000 enslaved individuals being forcibly migrated to the state during the first half of the 19th century.

This number was roughly seven times larger than estimated arrivals directly from Africa or via the Caribbean, the students concluded. Galveston was the main destination, but many other locations along the Texas coast were involved, from Sabine Lake to the Rio Grande. Moreover, from those documents, the team was able to pinpoint historical figures by name — like Mirabeau B. Lamar, the second president of the Republic of Texas — who had been slave owners.

In addition, they were able to uncover trends in the business operations of the Texas slave trade, tracing influxes in trading to points in Texas’ history or policy changes and gaining an understanding of Texas slave owners’ unique reliance on females and children.

“Both the prevalence of infants and children in the traffic and the balance of sex distribution differ significantly from the trans-Atlantic slave trade, which rarely transported infants and children and greatly favored male captives,” Schachter said in a presentation hosted by Fondren Library. “Slavers in Texas preferred these specific demographics, which they believed would provide physical and reproductive labor in the future.”

By the end of 2022, the team will be importing the newly uncovered data into the SlaveVoyages database, along with the names of the more than 15,000 enslaved people transported to Texas’ shores. “It is one thing to show data in the form of numbers. Another altogether is attaching names to these figures. It makes everything more personal, more human,” Domingues says.

For Zabarte, the names bring about more “real-world” connection points. “Taking this data and putting it on the website, especially the names of enslaved people, can allow people today to think, ‘Maybe these were my ancestors.’ If they’re reconstructing a family tree, they can actually find these people on the SlaveVoyages website instead of having to jump through all these hoops of traditional archives,” Zabarte says.

To her, that accessibility is key: “This is putting information into the hands of the people,” she says. “It’s giving them that opportunity, and I think that’s better than hiding it behind closed doors.”

The Coastwise Slave Trade

"Where is Texas on the SlaveVoyages website?” This question animates findings by recent graduates Katelyn Landry ’22, Victoria Zabarte ’22 and Ben Schachter ’22 along with doctoral student James Myers. Although the SlaveVoyages database is the largest repository of information about the trans-Atlantic and intra-American slave trades, information related to Texas’ involvement is largely absent from the 20-year project.

As Fondren Fellows, the team dug into archival records to fill in gaps in the narrative of intra-American slave trade into Texas ports. The findings from their yearlong project to reconstruct the 19th- century coastwise slave trade into Texas are on display in a remarkable poster exhibit at Fondren Library. By searching slave manifests filed in New Orleans, Savannah and Mobile between 1827 and 1860, the team discovered records of more than 15,000 enslaved Africans — including their names and other personal details — as well as the names of their enslavers and the ships that transported them.

“Our results show that the coastwise traffic to Texas started years before the 1836 Texas Revolution, that it peaked following statehood in 1845, and that it involved ports stretching from Sabine Lake to the Rio Grande, with Galveston being the principal destination,” they write on one of the illustrated posters. After the exhibit closes Aug. 19, 2022, it will travel to different cultural heritage sites managed by the Texas Historical Commission. By the end of 2022, this new data will be added to the SlaveVoyages database and will become available to the public for future discoveries.