Flood of Emotions

Two Rice faculty bring their perspectives on disaster to recent books about Hurricane Harvey and flooding in Houston.

By Laura Furr Mericas

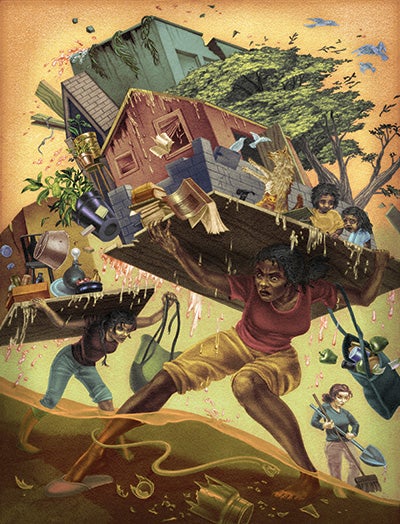

Illustration by Chloe Niclas

Rice researchers are no strangers to flooding. And how could they be? In Houston, where the Harris County Flood Control District estimates that a major flood occurs about every two years, flooding events have likely impacted almost everyone who’s set foot on campus.

From an academic standpoint, flooding has become the subject of intense study and scrutiny at Rice from institutions like the Severe Storm Prediction, Education and Evacuation from Disasters (SSPEED) Center; the Kinder Institute for Urban Research; and other scholarly behemoths that are leading discoveries and imparting wisdom in the field.

In recent months, two Rice faculty have broached the subject from distinctive and new angles, giving a voice to those whose stories have largely gone untold in Houston’s flooding anthology — providing readers with uniquely human lenses through which to view major events like Hurricane Harvey and the idea of disaster as a whole.

Rachel Kimbro, dean of the School of Social Sciences and professor of sociology, looks at the impact of flooding on a highly specific population: mothers, particularly those living in one Houston neighborhood. In her recently published book, “In Too Deep: Class and Mothering in a Flooded Community,” Kimbro lays out her sociological study of the affluent mothers of Bayou Oaks, a real Houston neighborhood (given a pseudonym in this publication) that flooded in the 2015 Memorial Day Flood, the 2016 Tax Day flood and again, catastrophically, in 2017 during Hurricane Harvey.

Through a series of 36 interviews — grouped into chronological chapters — Kimbro paints what’s often a murky picture of why residents choose to stay or come back to their neighborhoods post-disaster, particularly when social constructs, like school and an ideal family life, are at stake. Moreover, the book considers not only why, but also how these mothers (often without much help from their husbands) worked tirelessly to rebuild their homes and a sense of normalcy for their families — some for the third time.

“I am just like these women in pretty much every way,” Kimbro says. “What I really took away was the unbelievable amount of labor that these mothers were doing — cognitive labor, emotional labor, physical labor — to keep their families going during this really difficult time. They basically get no credit for that. That stuff, a lot of it is hidden.”

In a second work, set to release in June, Rice associate professor of creative writing Lacy M. Johnson — alongside Cheryl Beckett from the University of Houston School of Art, Graphic Design — takes a broader approach to yield a similar, human-focused result in “More City Than Water: A Houston Flood Atlas.” The structure is inspired by city atlases of San Francisco, New Orleans and New York by Rebecca Solnit, but tweaked to hone in on the specific subject of flooding.

Featuring essays, poems, conversations and maps to tell the stories of flooding from Pasadena to the Texas Medical Center to Houston’s west side from a diverse set of Houston-related writers — including Rice’s George Guion Williams Writer-in-Residence and Scholar-in-Residence for Racial Justice Bryan Washington, Houston Chronicle contributor Allyn West, Fulbright-García Robles Scholar Daniel Peña, Rice professor of anthropology Cymene Howe and Johnson herself — the book seeks to answer two significant overarching questions: “What does catastrophic flooding obscure about life in this city? And what does it reveal?”

A Man-Made Moment

Less apparent in Kimbro’s book, but plainly stated time and time again in “More City Than Water,” writers discuss the way human decisions have allowed for or directly led to the major flooding events of today — with Johnson and team zeroing in on how those events are felt by some more severely than others.

The creation of the Interstate 610 conveyance, which insufficiently channels Little White Oak Bayou underneath Independence Heights, has resulted in the flooding of Texas’ first Black municipality for the last 60 years. This stark example is presented in writer Aimee VonBokel’s essay “History Displaced” within the atlas. The Houston Ship Channel and its surrounding, largely minority neighborhoods — where residents “face ambient concentrations of seven separate pollutants at levels that pose a definite health risk,” according to the flood atlas — are almost their own characters throughout Johnson’s compilation.

“What I want people to understand or at least to begin to appreciate is that flooding, or disaster, is not an accident,” Johnson says. “In many ways, it shows us the ways that we are vulnerable, the people we need to take care of, and who we have not been caring for and what places we have not been caring for.”

In short, Johnson writes in the introduction of the atlas: “flooding reinforces the inequalities that surround us every day.”

Though achieving similar results, the major differences between “More City Than Water” and “In Too Deep” come down to class. Kimbro’s mothers, on average, lived in homes that cost about $450,000, with household incomes ranging from $75,000 to more than $400,000. They knew how to navigate bureaucracies, like FEMA and the National Flood Insurance Program, either through skills they picked up in their professions or through general “flood capital” (a term Kimbro coins) that they’d gained throughout the back-to-back disasters. Even the flooded-out mothers recognized their privilege, with phrases like “other people need it more” becoming a common refrain given to those offering help in the post-Harvey cleanup and one mother telling Kimbro “we are not destitute.”

What I want people to understand or at least to begin to appreciate is that flooding, or disaster, is not an accident,” Johnson says. “In many ways, it shows us the ways that we are vulnerable, the people we need to take care of, and who we have not been caring for and what places we have not been caring for. — Lacy M. Johnson

Still, the reality of flooding isn’t rosy no matter the demographic. Both books discuss the emotional impacts of the storm. Sonia Del Hierro describes an “ineffable, body-deep fear” when mucking out her apartment post-storm in her poem “Harvey Alerts,” included in the atlas. Mothers from Kimbro’s interviews shared about the marital strife and therapy sessions required for their children as a result of the storm and the recovery that followed.

And yet, despite what each book presents, they both reveal ways in which human decisions will almost inevitably continue to play a role in future flooding events and their impact. Twenty-eight out of the 36 mothers interviewed for “In Too Deep,” for instance, chose to rebuild or remodel in Bayou Oaks, despite their general assessment that it would flood again and the fact that “virtually all of the mothers understood and endorsed the concept of climate change, including how it could impact Bayou Oaks,” Kimbro writes.

In Roy Scranton’s essay “Anthropocene City” in the flood atlas, he describes these types of post-disaster decisions as such: “Unfortunately for us, we’re still not very good at controlling the future. What we’re good at is telling ourselves the stories we want to hear, the stories that help us cope with existence in a wild, unpredictable world.”

Natural Reactions

Both books would likely be considered deviations from Kimbro and Johnson’s work to date. “In Too Deep” trades Kimbro’s traditional academic style of writing for a more reader-friendly narrative arc. And though much of Kimbro’s work has focused on the concept of neighborhoods and how they can influence individuals and children outside of the family, “In Too Deep” represents the dean’s first foray into the subjects of environment and natural disaster.

Johnson, on the other hand, has touched on environmental issues in her previous work and is a founding member of the Houston Flood Museum. She’s largely known for her writing and work around domestic violence and sexual assault. To her, however, pivoting to focus on issues of catastrophic flooding seems like only a minor shift.

“Both the issues of domestic and sexual violence and questions of climate change, climate catastrophe, environmental injustice — it’s about abuse of power,” she says. “And in both instances, it’s about the kind of harm and trauma of having another person exert their will over you and the lasting harm that that does.”

It may come as no surprise that both books’ styles — their authors’ backgrounds aside — were born out of visceral reactions to Hurricane Harvey. “There was this disbelief that this neighborhood that had just finished repairs would flood again and worse,” Kimbro recalls. “It was like a bolt from the blue. It felt very critical to me to tell this story. And I have never felt this way before about a project.”

What I really took away was the unbelievable amount of labor that these mothers were doing — cognitive labor, emotional labor, physical labor — to keep their families going during this really difficult time. They basically get no credit for that. That stuff, a lot of it is hidden. — Rachel Kimbro

For Johnson, the feeling was anger. “Harvey certainly made me mad,” she says. “Not just because of the experience of the storm itself, but that kind of collective amnesia about it. I’ve heard the definition of insanity is to believe that you can continue doing the same thing and expect different results.

And here we are, doing the same thing over and over and over: more development, more oil, more drilling, more fracking, more emissions and thinking that it’s not going to keep happening and keep getting worse.”

Both steer clear of making specific recommendations for policymakers and flood experts.

Rather, each author hopes that by presenting a more human angle, readers’ and even leaders’ eyes will be opened to a deeper understanding of how catastrophic events impact Houstonians on a micro or personal level — with an implicit understanding that those effects will continue to be felt until real, impactful changes are made.

“I wanted to highlight the fact that climate change is encroaching on our communities and will continue to do so,” Kimbro says. “That actually involves real families, real people who are having to make decisions about what to do. I think that’s going to become more and more common, whether it’s wildfires or floods or ... name your disaster.”