Meditation for this Moment

To combat stress caused by COVID-19, I take refuge in an ancient practice of meditation — and you can, too.

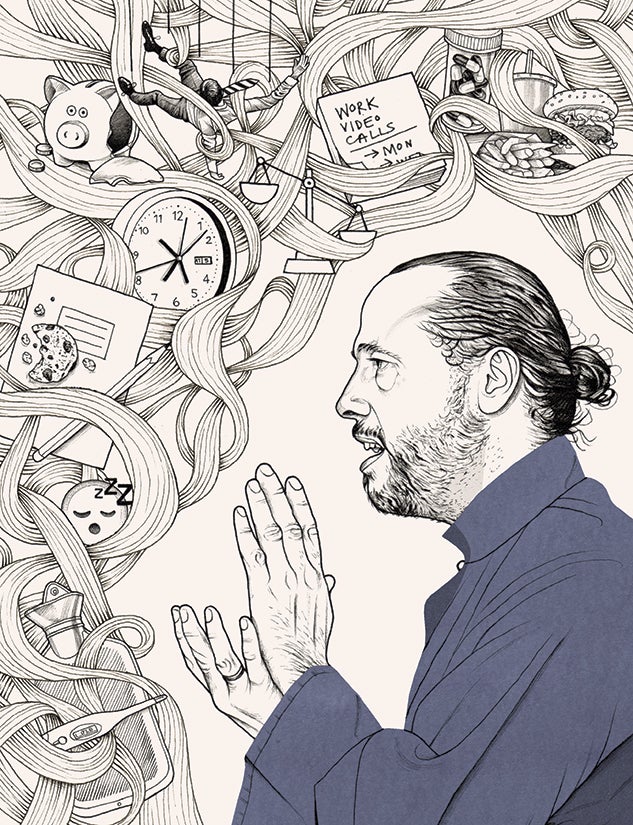

COVID-19 has hijacked our amygdala — the reptilian part of the brain that helps regulate emotions and motivations, particularly those related to survival. This reptilian brain has taken charge, causing us to adopt a fight-or-flight response mode in our daily lives. Usually, once a stressful situation is over, the brain gets back to “normal.” But when we don’t have time to rebalance our system between increasingly dire or stressful events, we may fall into a kind of chronic stress.

This is the case for many people today as the worries and anxieties associated with COVID-19 pile up.

Chronic stress has shown to have deleterious effects to almost all the biological systems in our bodies. Unmanaged, it can speed the aging process through shortening of our telomeres, which protect the integrity of our chromosomes, and increase the risk for heart disease, sleeping difficulties, digestive problems and even depression. Chronic stress also causes us to forego healthy eating and exercise habits — does this sound familiar?

I was born and grew up in Argentina. At a young age, I had what I called “existential attacks.” I would wake up, sweating, with terrible uncertainty of what will happen to me after I died. From my crunching stomach to a mind imagining worst-case scenarios, I could feel a deep sense of anxiety.

When I was just a bit older, I read the novel “Siddhartha” by Hermann Hesse. The story spoke about the sufferings of birth, old age, sickness and death, and about meditation and other practices to appease one’s relationship to these sufferings. I soon realized that “Siddhartha” was a novel about the life and teaching of the Buddha, and that knowledge led me to find a meditation teacher and to start a daily meditation practice. This helped me deal with my chronic anxiety

After graduating college, I traveled to India and Nepal, where I spent almost a year and met many Hindu and Buddhist teachers, including the Dalai Lama. That trip changed my life, and meditation became a central part of my lifestyle. Before long, I returned to Nepal to learn more about Tibetan yoga and the different forms of Tibetan Buddhist practices. That desire for learning eventually brought me to the University of Virginia, where I earned a master’s degree in religious studies. There, I learned about the science of meditation and was especially fascinated by the work of Herbert Benson, a cardiologist and the founder of Harvard’s Mind/Body Medical Institute.

Benson’s research showed that meditation can counteract chronic stress and introduced the term “relaxation response.” This response explains the mechanism that counteracts the fight-or-flight impulse, rebalancing the sympathetic and parasympathetic systems so that the person can resume with a sense of normalcy.

We don’t always have to be in the perfect space to learn about and practice meditation.

In 1996, I came to Houston to pursue a doctorate in religious studies at Rice at the suggestion of my Tibetan teacher, Tenzin Wangyal Rinpoche. At the time, he was a Rockefeller fellow working with Anne Klein, a professor of religion at Rice, helping to translate ancient Buddhist texts. I had the wonderful opportunity to learn the academic aspects of Tibetan spiritual practices as well as deepen Tibetan mind-body practices like meditation and Tibetan yoga with my teacher and the meditation community in Houston. I also unexpectedly discovered a new focus for my career.

My dad, who at that time had recently been diagnosed with prostate cancer, was visiting Houston and asked me to go with him to MD Anderson for a consultation. Luckily, all went well with his treatment, and my dad has been healthy and cancer-free for more than 20 years. That visit to MD Anderson opened the door for me to apply my academic studies and personal meditation practice as a resource for people touched by cancer.

I started as a volunteer, teaching meditation practices to cancer patients and their caregivers. By the time I graduated from Rice, I had started working as a mind-body intervention specialist at MD Anderson. With a few colleagues, we had also published our first study on the effects of practicing Tibetan yoga in a group of lymphoma patients. Some of the benefits included better sleep quality, quantity and latency — the time from when you want to sleep until you fall asleep — and less use of sleep medicine. In addition, patients in this group had fewer intrusive thoughts and reported having an increased spirituality.

In other words, mind-body practices like meditation, mindfulness and yoga did not cure cancer, but they significantly improved quality of life and symptoms. In my two decades as a teacher at MD Anderson, I have led weekly meditation classes for patients and caregivers, continued to conduct research on the potential benefits of mind-body practices in people touched by cancer and directed the educational programs of integrative medicine.

As our family realized the dangers of COVID-19, we canceled spring break plans with our college-age children. Then came the news that both of their colleges, like Rice, would continue instruction online for the rest of the semester. We had to readapt our empty nest and plan how to divide the house into workstations. We also had to adjust to buying more groceries and doing more laundry, all the while listening to our children’s rap music.

The silver lining of this pandemic is having our children back at the house and spending more time together as a family without social distractions. I got to spend my birthday with them, which hadn’t happened since they were in high school. My wife, Erika de la Garza, who worked at Rice’s Baker Institute for Public Policy, and I started a morning routine to keep our sanity. The routine begins with meditation and Tibetan yoga movements and ends with enjoying several cups of mate — an Argentine beverage that tastes like a strong tea. Meditation and mind-body practices (and for me, sharing a cup of mate every morning) can help one cope, feel a little better and reconnect to a sense of normalcy.

We don’t always have to be in the perfect space to learn about and practice meditation. In fact, sometimes when our life is going along as usual, we don’t reach for mind-body tools such as meditation because we don’t feel we need such practices. It is when our lives feel threatened or when we are facing difficulty that the reptilian brain is aroused as a survival mechanism, and we look for anything that may help us calm down a bit.

Today, I continue to lead weekly meditations — many just 15 minutes long — for different audiences, including physicians and other health care providers in the Texas Medical Center. These short meditations can serve as an oasis in a long day, a way to connect and breathe into a sense of inner space in our inner home.

A simple practice one could do is called the STOP formula. Following the acronym, Stop whatever you are doing in that moment, then Take a deep breath (bring your breath all the way down to your abdomen, not just your chest), Observe how you feel and then, only when you are ready, Proceed to what you need to do next.

For me, it is important that we think of this time and the lessons learned in the context of our communities. It’s not just about one of us learning from these experiences, but each of us, so that we can have a whole community of flourishing individuals. As we continue dealing with the stresses of this pandemic, we cannot meditate the virus away, but meditating can help people cope and improve their well-being.

Alejandro Chaoul is the founder of the Mind Body Spirit Institute at the Jung Center in Houston, where he leads regular meditation practices and other programs. Learn more at mbsihouston.org.