Apocalyptic Times

What I learned in my religious studies courses at Rice helps me understand what the COVID-19 pandemic is revealing about the brokenness in contemporary society.

On Sept. 11, 2001, I was one month into my freshman year at Rice. That Tuesday morning, my suitemates and I woke to the sound of the (landline!) phone ringing. It was my suitemate Rebecca’s dad, calling to tell us to turn on the news. We did, watching in disbelief as the second plane hit the World Trade Center tower. The rest of that day unfolded in a daze. I walked to the Humanities Building only to discover that classes had been canceled. I sent frantic emails to check up on friends and family members living in D.C. and New York. Finally, I headed to Fondren Library, where I spent the day in an oversized chair, devouring Annie Dillard’s “An American Childhood” in one sitting until the light outside grew dark. That night in the Baker Commons at dinner, we all wondered: Would a war break out? Would the draft be reinstated? Would we be sent home?

Over the coming weeks, daily life for most of us returned to normal, the aftereffects of 9/11 having primarily to do with cumbersome airport protocols and increased attention to the news and international politics. I had matriculated at Rice with the intention of studying religion, much to the chagrin of many adults in my life. “What are you going to do with that?” became a question I regularly fielded. But in the wake of 9/11, my area of study ceased to puzzle; as interest in Islam grew and misinformation spread like wildfire, what had previously struck people as an esoteric, impractical area of study suddenly seemed intensely important and real. My decision to major in religious studies was cemented.

Engaging in the academic study of religion felt akin to walking into the Library of Congress for the first time; I spent a lot of time walking around in wonder. I read voraciously, fascinated by the way that my major encouraged me to dig ideas up by their root, to seek the full picture rather than assume what was visible aboveground told the whole story.

Early on in my studies, I discovered that many words I assumed I knew the meaning of had different uses in an academic context. For example, among scholars, “cult” is a neutral term that refers to a new religious movement whose practices or ideas are considered reprehensible by their contemporaries. By this definition, Jesus and his followers are considered a cult movement; it is only after Jesus’ death and the work of Paul that Christianity becomes an organized religion.

“Apocalypse” is another word whose meaning varies greatly depending on its context. Though most of us think of action heroes and fiery landscapes when we hear it, the word’s etymology is quite different. Apocalypse comes from the Greek “apokalyptein,” which is itself a joining of the prefix apo-, meaning “off, away from,” and the root kalup ein, meaning “to cover or conceal.” Therefore, apocalypse literally means “to uncover or reveal.” Even the term “revelation,” which we associate with the end of the world, is much more about the end of a current age, a reckoning that brings about desperately needed change.

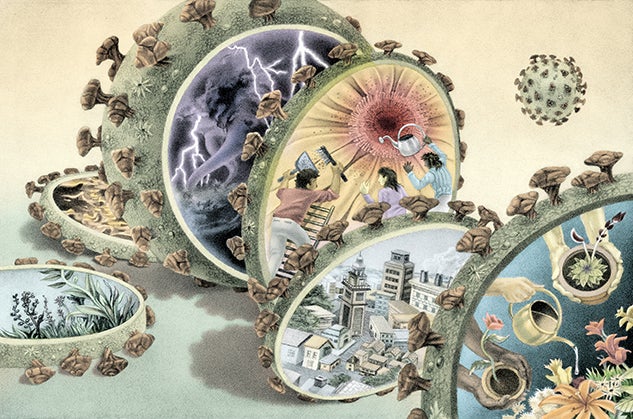

So for me to say that we are living in an apocalyptic age is not to invoke futuristic, dystopian imagery, but rather to argue that the current global pandemic is showing us a great deal about the brokenness of contemporary America: the inequality of our systems (particularly health care), the gaps in our infrastructure, the frailty of our social safety nets, our cultural discomfort with uncertainty and grief. Populations that were already marginalized and vulnerable — indigenous and African American communities, the elderly who live in nursing homes, incarcerated Americans — are the ones who face the highest rates of COVID-19 infection. Unemployment is at a record high and food banks are struggling to provide assistance to citizens of one of the richest nations in the world.

Our mythology of exceptionalism and insistence on rugged individualism have blinded us to our interdependence on the natural world and on each other; the cost of this blindness is high, with climate catastrophe lurking on the other side of this pandemic. I may have first unpacked the term “apocalyptic” while studying the messianic beliefs of the first century of the common era, but what I learned about human dynamics and the beliefs that we live and die by are as applicable as ever.

This fall marks my 15th reunion year; the nervous speculation that my classmates and I felt during the fall of our freshman year has been overtaken by a pervasive and indefinite uncertainty that forced this year’s graduating class off campus in March instead of May into a world turned upside down. The religious studies major in me can’t help but wonder what will be revealed to them.

Nishta J. Mehra is the proud first-generation daughter of Indian immigrants, a high school English teacher and the author of two essay collections: “The Pomegranate King” and “Brown White Black: An American Family at the Intersection of Race, Gender, Sexuality, and Religion.” Mehra lives with her wife, Jill Carroll, and their children, Jesse and Shiv, in Phoenix.