Georgia's Legacy

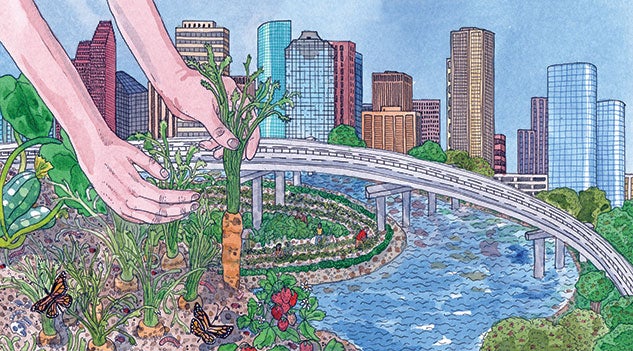

A visionary leader, scientist and entrepreneur, Georgia Bost ’72 left an outsized legacy that continues to nurture Houstonian’s hunger for healthful eating.

Summer 2017

The farmers market near Richmond and Eastside is a magical place on Saturday mornings. Shoppers wander from booth to booth, tempted by carrots just plucked from the dirt, beets the size of softballs, Brussels sprouts still on the stalk. But the glistening vegetables are only part of the show. Vendors also sell mounds of perfectly ripe fruit, duck eggs, cheeses, pasta, grass-fed beef, native plants — all locally produced.

Georgia Bost, the scientist-farmer who helped sow the seeds for this bustling market, died in 2012 at the age of 62, three years after she was diagnosed with breast cancer and early dementia. Her death was a tragic loss — she was a pioneering horticulturist and teacher who helped change the way Houstonians think about food.

Bost pictured in the 1971 Campanile.

As far back as the 1970s, Bost dedicated herself to organic gardening and native plants that could flourish without pesticides or extensive watering. She was a dedicated scholar researching native hibiscus plants, creating hybrids that were not only beautiful but edible. During her research, she discovered that the hardy plants even sucked up toxins from the soil.

“She was a rocket scientist in the way she used plants to help people and society,” says Mark Bowen, a horticulturist and native plant specialist who worked closely with Bost in her heyday. “She definitely helped Urban Harvest (a local nonprofit that teaches people how to grow their own fruits and vegetables and sponsors local farmers markets), and she was a great person to bounce ideas off of. She was always the smartest person in the room.”

Bob Randall, Urban Harvest’s first executive director, remembers Bost’s passion for chemical-free, environmentally friendly and energy-efficient gardening. “Some leaders are motivated by power or wealth, and some are interested in helping others to lead a better life,” Randall says. “Georgia was in that second group.”

Bost was born and raised in Ponca City, Okla., where she was high school valedictorian. But by graduation, she was ready for a big city and a college environment that fostered big ideas.

A third-generation Rice University graduate, Bost arrived on campus in 1968, ready to combine her love of horticulture and ecology. If both were considered men’s fields back then, she paid no attention to the gender barriers. If men talked past her on subjects she was interested in, she just persisted until they realized she knew as much or more than they did.

Richard Bost, a graduate school colleague who eventually became Georgia’s second husband, remembers that she was advocating for organic and sustainable gardening before most Texans knew what she meant.

At a legendary Montrose restaurant called the Hobbit Hole, Randall, Bowen and other ecologically minded friends, including Georgia, met to figure out ways to share their gardening knowledge. One of the steps was a group called TexUS ROOTS. The wonky name translated to Texans for Urban Sustainability, a Regional Organization for Organic Technology and Sustainability.

“We can do this,” Bost used to tell her friends. “Y’all can teach classes at my place.” No surprise, she was the group’s first president.

By middle age, Bost already had served as what Randall described as a servant leader at Urban Harvest. She also was heavily involved in gardening education — whether she was teaching third graders or landscape designers — and she was traveling throughout the South to continue her study of hibiscus. During the course of her research, she earned seven patents.

If Bost was flourishing professionally — by then she had her master’s in ecology and juggled multiple projects at once — she was struggling personally.

An early first marriage ended in divorce, leaving Bost a single mom. But the true heartbreak wasn’t the divorce. Nathan, Bost’s adored son, was diagnosed with leukemia at age 5 and died at age 12. The final blows were a blood transfusion that carried the AIDS virus and a heart attack.

By then Richard and Georgia were married and the proud parents of a daughter, Michelle, and a son, Martin. In their Spring Branch neighborhood in the late 1980s, Georgia opened a store called The Village Botanica. It was a nursery, pottery studio, art gallery, and arts and crafts supply store all in one.

“I think the idea of VB grew out of recognizing how fragile and short life is and wanting to have a store composed of all the things she and Nathan loved,” says Michelle, a San Marcos physician whose married name is Rodriguez. “She realized that the corporate world, at least at that time, was more of an old boys’ club than she cared to bother with.

“In some ways,” Michelle says, “she never got over my brother’s death — does anyone truly get over the death of a child? Looking back, I realize she struggled with depression for years. I think it also gave her a sense of urgency, that her time was limited and she needed to make as much use of it as possible.”

By middle age, Bost already had served as what Randall described as a servant leader at Urban Harvest. She also was heavily involved in gardening education — whether she was teaching third graders or landscape designers — and she was traveling throughout the South to continue her study of hibiscus. During the course of her research, she earned seven patents.

When Michelle and Martin were still in their teens, Georgia and Richard bought a farm in Waller County that came to be known as Hibiscus Hill. There Bost continued her passion for organic farming on a large scale. She also raised grass-fed beef and made sure the cattle were treated humanely in life and at the processing plant.

Bost’s final businesses were two stores that sold meat, produce and ready-made foods. As always, her focus at Georgia’s Farm to Market, one in Spring Branch and one in downtown Houston, was on organic inventories produced locally.

“We come from the earth and we return to the earth,” Michelle Rodriguez says. “My mother’s goal, as I saw it, was to honor that gift by farming in a way that made the least impact on our ecosystem.”