She Runs

Becky Wade ’12 spent a year after graduation living, working and running with some of the world’s fastest and most fascinating athletes.

Summer 2016

By Becky Wade '12

Photos by Jeff Fitlow

“The Devil is in Derartu. Today very, very not strong.”

Stretching at the base of Mount Entoto, 8,500 feet above sea level, I caught my breath after lagging behind Banchi and Meseret in that morning’s hill workout. I had an excuse ready: I’d arrived in Ethiopia only days before and would need several weeks to acclimate to the time zone and altitude. I longed to prove to these women that I was also a serious runner, having competed at the U.S. Olympic Trials and at the World Junior Track and Field Championship, but neither my language nor my lungs would let me. I’d have to gasp my way through the girls’ “easy” runs, watch helplessly as they pulled away from me in workouts like this one, and grin with every shout of encouragement. “Aizosh, Becky!” “Berta!”

Derartu, though, was struggling. The 22-year-old, born and raised in Sululta, a town 10 kilometers outside Addis Ababa, could normally hold her own against the other two. Pound for pound, my five-foot friend was one of the stronger distance runners I’d encountered, with the quads of a soccer player and the spring of an antelope. But you’d never know it if you saw her that morning.

As Banchi and Mesi bounded up the dirt road, Derartu lagged farther and farther behind. Glistening with sweat, a grimace on her face, she looked more like the local firewood carriers who piggybacked buffalo-size bundles up the mountain than she did her fleet-footed training partners.

In broken English and the same nonchalant tone she used to describe doro wat and shiro at dinner the night before, Banchi explained Derartu’s dilemma: The Devil was inside her, sapping her strength.

I’ve never wished more than in that moment to understand a foreign tongue.

But given the English-to-Amharic language gap — not to mention cultural chasm — I had to rely on a bare-bones explanation and my own limited experience to make sense of what I had seen and heard.

I thought back to the blue Rice University track in Houston, Texas, where I’d spent the past five years chasing faster times in the 10,000 meters, 5,000 meters and 3,000-meter steeplechase, and tried to imagine the same conversation.

“Sorry, Coach Bevan, but I can’t finish the last mile repeat [hard interval] today.”

“What’s going on? Are you getting that weird sensation in your lower legs again?” my coach of almost a decade, Jim Bevan, would ask, probably dreading the details about my latest injury.

“No, it’s not that. I’m not hurt. It’s just that the Devil is inside me, and he won’t let me finish the workout.”

There was a long list of excuses that my forgiving coach would accept from his runners — a stomachache, a sleepless night, poor recovery from the last workout, even a recent breakup — but inhabitation by the Devil had no place in it.

Worlds away in Ethiopia — the cradle of humanity, and of many of the world’s best endurance athletes — Banchi’s explanation wouldn’t be given a second thought. In fact, it was one of the more acceptable reasons that Derartu, one of the most privileged runners in the area, would be too weak to complete a hill session. Along with Banchi and Mesi, she had raced her way to a scholarship that entitled her to four months of comfortable housing, balanced meals, English and career-skills lessons, and her first structured running environment.

The Yaya Girls, named after the Yaya Village hotel and training camp where I lived and volunteered for two months, were the envy of Sululta, living like royalty compared to most of their family members and neighbors, whose homes were typically shacks lacking electricity and running water. The girls were still learning how to reconcile this new, temporary existence and its many resources with the familiar, simpler one that awaited them at the end of the program. They slept two to a twin bed for comfort when there were enough beds for all and declined the pre-run breakfasts offered each morning. Clearly the lifestyle preferred by first-world runners was not universally considered ideal.

Less apparent was if and how, by exposing Banchi, Mesi, and Derartu to new elements such as a varied, meat-inclusive diet, a strength program and fresh shoes, the Yaya Girls Program was tinkering with their potential as runners. Would such added comforts keep my friends healthier and more focused, or make them softer athletes, more likely to fold during key decision points in a race? Conversely, I wondered how adopting some rural Ethiopian practices — the very ones which we were tweaking — might influence, even enhance, my own running. Would a huge leap in the distance I walked daily interfere with my training? Would treating every Sunday as a day of rest make me a more consistent runner, or less fit? And how would a nutrition plan that emphasized grains over fruits and vegetables, and little protein, affect my energy and ability to recover?

I had about eight weeks to find some answers. Then it would be time to pack up and start again in a new country. That morning, I accepted that I’d probably never fully grasp Banchi’s reasoning about Derartu and the Devil — which I later learned was a blend of Ethiopian Orthodoxy and religious superstition, both foreign to my Catholic upbringing. But I was committed to trying, as I remained open-minded to other cultural beliefs and practices that inform how communities like the Yaya Girls approach long-distance running. I was searching for meaning in the universal phenomenon of running — the oldest, purest, and most global of all sports — and, just maybe, an edge on my competition down the road.

A year earlier, I’d stood firmly on the opposite side of the world. I had lived in Texas all twenty-two years of my life, other than a few summers spent training in Colorado, and I was anxious to flee the coop, to see what the wider world could teach me about living, connecting and, naturally, running. A scholarship athlete at Rice University and a runner since the age of nine, I had engaged in the sport as it was dictated to me: practice schedules, track repeats, travel itineraries and rehab plans.

My goal the past five years had become sunup-to-sundown productivity, punctuated by two runs most days and peppered with naps, ice baths and ample time to cook and eat, even as I streamlined my nutritional and social needs. When my graduation from Rice approached, I faced an open-ended running future for the first time, and I wasn’t sure what to make of it.

The prospect of copious free time and a more active social life was attractive. Would my body finally learn to sleep past 6 a.m.? What would it feel like to eat a hamburger and fries at lunch, not having to hold back for a looming afternoon workout? How many beers would I have to consume to catch up to my twin brother, Luke?

But I also didn’t feel quite ready to find out. I was wrapping up a fruitful career at Rice that included four NCAA Division I All-American Honors and two Olympic Trials qualifiers, and I was miles away from wanting to hang up my spikes. I felt shortchanged in my college career due to a string of injuries, and I was young and fresh by long-distance standards; I’d mainly focused on the 300-meter hurdles until college, and female marathoners typically don’t peak until their mid-thirties—if they stick with it that long. Most important, I still had a deep, childlike love for running. Finding new routes, learning the nuances of my body, forming relationships on the move and challenging myself at various distances still excited me, more than a decade after I first laced up a pair of Sambas and circled the block with my dad. I couldn’t fathom a life without running as a huge part of it.

At Rice University, where I competed from 2007 to 2012, my passion for running soared. Now, with my newfound independence, I wanted to be more deliberate with my running. To question the practices I had assumed were best, test how much of myself I would invest when the leash came off, and ultimately, find a balance between freedom and structure. Recalling Coach Bevan’s philosophy that “a happy runner is a fast runner,” I was on a mission to synchronize my heart and my feet.

The most pivotal event in my running career up to that point was the 2008 World Junior Track and Field Championship, in Bydgoszcz, Poland. While debuting on an international stage in the 3,000-meter steeplechase, I first glimpsed the full spectrum of approaches to track and field. The Team USA distance squad emphasized short and easy runs in the days leading up to our races, while the Ethiopians continued running intense interval workouts. The Japanese team warmed up in silence, looking solemn and fierce, contrasted by the Italians chatting their way around the practice field. Differences emerged away from the track, too, as the athletes relaxed and supported one another. The Swedes runners always had a card game going in the hotel we shared, seemingly to help calm their nerves; the South African team performed infectious celebratory dances; and the Irish athletes and coaches were the clear extroverts of the bunch, requesting pictures and singlet swaps with everyone who passed by their training tent.

How all of those rituals influenced competitive performance, I couldn’t tell. Though the usual suspects excelled in certain disciplines — the United States and Jamaica in the sprints, Kenya and Ethiopia in the distances, and Germany in the throws — there wasn’t an obvious overlap in the approaches of the victors. More clear to me was the idea that having such rituals, and believing in them, went a long way in each competitor’s experience of the event. In other words, the culture of a team, reflecting the place it comes from, seemed to matter. I left Poland not only with a suitcase full of new uniforms I’d traded for but also the desire to explore some of those cultures firsthand, and to apply my discoveries to my own running endeavors. Four years later, I’d get my chance.

The Thomas J. Watson Fellowship sounds like one of Willy Wonka’s Golden Tickets.

Awarded annually to 40 graduating college seniors “to enhance their capacity for resourcefulness, imagination, openness and leadership and to foster their humane and effective participation in the world community,” it basically funds the dream year of each recipient. Relying on a strict budget, each fellow spends 12 months traveling the world independently in pursuit of a personal passion — from beekeeping and meditation to unicycling and, in my case, long-distance running.

I proposed to spend my first year out of college diving into foreign running communities, searching for both unique and common ways that people around the world approach running and construct their lives around it.

To find the pulse of each place’s running climate, I wanted to tackle all angles: jogging with recreational enthusiasts, questioning coaches about training philosophies, emulating the routines of professionals, interviewing running historians, tracking down retired legends, watching and competing in races, and exploring the trails and courses that locals loved most.

My original agenda, hatched through obsessive research and with the help of hundreds of contacts, included England, host of the 2012 Olympic Games and a strong club culture; Ethiopia, nest of countless endurance phenoms; New Zealand, birthplace of the jogging boom and one of the world’s most influential running coaches; Japan, home to a famously disciplined running regime; and Finland, the tough and tiny nation that, having topped the long-distance world two separate times in the last century, epitomizes the ebb and flow of athletics. My curiosity was driven by the running culture I grew up in — a pressure cooker in which every result is scrutinized and Type A personalities are the norm. I loved it, but at times was left frustrated and drained.

Once I got on the road and started toying with the incredible flexibility of the fellowship, those plans evolved into a more organic strategy. The apartments and hostels I budgeted for? I only needed a few, in my very first destination and for the occasional rendezvous outside my base city. Eventually, I strung together 72 sleeping arrangements, most of my hosts in some way connected to their local running community and willing to open their doors to this small, curious American runner. The handful of countries I proposed to visit? I began using the money I saved on housing toward plane, train, and ferry tickets.

Before I knew it, five countries had snowballed into 22, some that I briefly explored in transit, and a dozen in which I lingered for at least a week and in some cases up to two months. …

The real crux of my journey would defy research and planning. There would be discoveries about running and recovering; recipes gathered from hosts in each country; growth in adaptability and openness to new training methods; and relationships built with runners all over the world. My assumptions about the formula for athletic success, and the essence of distance running, would be both affirmed and shattered.

Banchi’s explanation for Derartu’s struggle — the Devil — was one of many obvious differences that I encountered in Ethiopia and elsewhere from the classical American approach to running. The disparities among cultures struck me earliest and hardest, but similarities were abundant as well. With few exceptions, Sundays are universal long-run days, and kilometer repeats (or mile repeats for U.S. runners) are a bread-and-butter workout.

Oats — in the form of porridge in the United Kingdom, muesli in Switzerland, and pancakes in Scandinavia — are the breakfast of champions the world over. Runners across the globe never seem to get their fill of tea; the Finn Valley Athletics Club in Donegal, Ireland, ends each daily session with hot tea and scones in the clubhouse. And somehow, amid all of that caffeination, distance runners everywhere with the luxury to do so treat afternoon naps as seriously as business meetings.

Deviation from the all-or-nothing, gadget-driven, results-obsessed training style pervasive in the United States is neither comfortable nor secure. But stepping outside a conventional approach offers great potential to extend careers, foster unexpected connections and find fulfillment in running’s simplest form. Five months after returning from my trip and cherry-picking from each training style I encountered led me to the third-fastest marathon time in American history for a woman under age twenty-five and a contract with Asics, a shoe company with Japanese roots and a worldwide reach.

More important, my experiences running with athletes in different cultures laid the foundation for a future of continued joy and friendship found through running. In these pages are many of the lessons, techniques, and rituals I encountered on my journey. Some I have incorporated into my own life, others I have included simply because they fascinate me. Together, they power the heartbeat of the global running community.

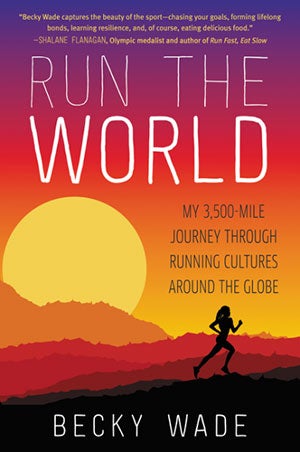

Adapted from “Run the World: My 3,500-mile Journey Through Running Cultures Around the Globe,” (William Morrow, 2016).