The Dam

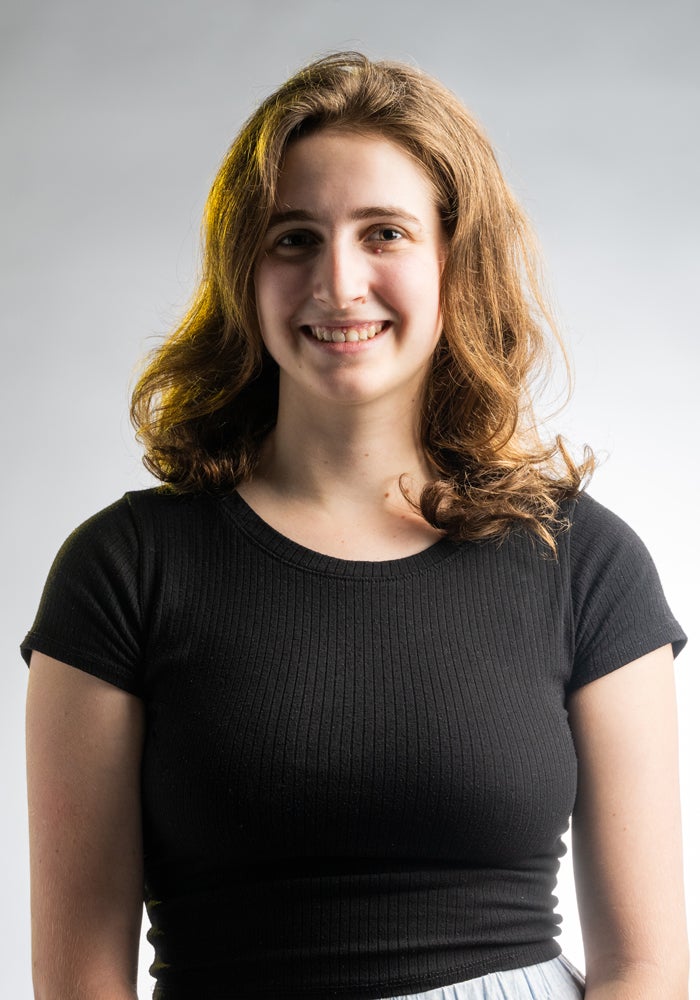

Sarah Davidson brings a humanist’s perspective to a complex story about economic development and environmental justice.

Spring 2025

By Hugo Gerbich Pais ’25

When a dam fails, most would turn to scientists and engineers. But what happens when the problem isn’t concrete and steel? The interdisciplinary work conducted by senior Sarah Davidson illustrates that humanists play a vital role in understanding how economic development and the built environment can impact society.

The Ituango hydroelectric dam — the largest dam in Colombia — was not on Davidson’s radar when she came to Rice or when she was selected as an Elizabeth Lee Moody Undergraduate Research Fellow in the Humanities and the Arts. It was Rice historian Laura Correa Ochoa who suggested that she consider researching the project. “I was very interested because I had been doing projects on environmental justice and infrastructure and how it affects people in the surrounding communities,” says Davidson.

The complexity of Colombia did not stop Davidson’s research, says Correa Ochoa. “[Studying] Colombia can be so tricky, and she seems so unfazed by it all. She was just like, ‘Yeah, I’ll go to the archive and figure it out.’”

The Moody Fellowship allowed Davidson to spend last summer researching the dam, which included a visit to Medellin, Colombia. “Being there helped me to get a broader cultural perspective,” says Davidson. “Just talking to people there about what had been going on for the last 60 years and the conflict that had happened within the city and the surrounding area helped.”

Davidson says she wanted her project to be digital and public-facing. She settled on using ArcGIS StoryMaps, a software she discovered at Rice that allows its users to create interactive multimedia digital exhibits. “A lot of the [impact of the dam] is hidden in these lengthy government documents and reports, and [ArcGIS] allowed my findings to be more accessible to the public,” Davidson says.

Her StoryMaps project, titled “The War for Hidroituango: The history of violence, power, and hydroelectric energy in Antioquia, Colombia,” combines archival materials, government documents, newspaper articles and photographs. It traces the dam’s history and impact from its original conception in 1950 to its eventual opening in 2022 — a period that was marred by paramilitary activity, displacement, massacres, engineering failings, corruption and flooding.

Importantly, the phenomenon she investigated in Colombia isn’t unique. “There is this pattern that goes on. This happened in Ghana. It happened in Guatemala. It’s happening in so many different places,” Davidson says. “[Dams] are this sign of modernity — the sign of wealth being brought to the country. And at the same time, it often is only something that will benefit the wealthiest and the most powerful in society, rather than many of the marginalized individuals who live by these hydroelectric projects.”

Laura Correa Ochoa is assistant professor of history in the School of Humanities.