Think Like An Architect

Read and be inspired by the mindsets that fuel these Rice archis.

By Erin Peterson | Illustrations by Agata Nowicka

We spend our days in built environments: homes and office buildings, grocery stores and post offices, malls and hospitals, and bus stations and libraries. At the heart of all of these structures is an architect who imagined them and helped shepherd them into reality.

But how do architects think about their work? What sparks their imagination, drives the decisions in their floor plans and fuels the creativity that allows them to see the world in a new way — and bring that vision to life?

To find out, we asked alumni and faculty architects about the foundational mindsets that propel their work. We think the ideas they share are surprising and beautiful. And they might just make you look at the places you spend your time in an entirely new way.

Use Environment to Influence Behavior

Danish Kurani earned a Bachelor of Arts in 2007 and a Bachelor of Architecture in 2009. He is the founder of Kurani, a firm that designs learning spaces for schools, cultural institutions and other organizations.

Kurani frequently works with organizations that want to upend traditional learning. As an architect, he aims to help institutions achieve those ambitions through design that literally changes behavior.

For example, to discourage traditional lecture classes, he might design a space so that there’s no obvious front of the classroom for a teacher to stand at a lectern. He might add small clusters of tables to encourage peer-to-peer collaboration, rather than rows of individual desks facing a whiteboard. “We make thousands of decisions with every project, and those decisions can either help or hinder behaviors,” he says. “You can encourage behaviors with the right setting.”

In a recent project for a nonprofit that encourages kids to become makers, Kurani’s firm designed tables with distressed surfaces as opposed to pristine ones. “I didn’t want anyone to feel like, ‘I don’t want to be the first one to scratch it or get paint on it,’” he says. Even drawer pulls in the space have playful shapes, suggesting that every detail of an experience can be re-imagined in purposeful ways.

For Kurani, architecture is an important tool to improve the world. “I really believe we can nudge people by using their environment as the catalyst,” he says.

Taking a Holistic Approach to Realize Your Responsibilities and Impact

Florence Tang earned a Master of Architecture in 2009 and is a design and engineering project manager at the Houston Zoo. Scott Colman is an assistant professor of architecture at Rice.

In her work for the Houston Zoo, Tang has to think about satisfying many audiences simultaneously. That means toddlers, grandparents, families with strollers and kids who want to put everything straight into their mouths.

And that’s just the people.

She and her team have also helped create or renovate some of the spaces for the zoo’s thousands of animal inhabitants, including tropical wetlands for jaguars, giant anteaters, giant river otters, howler monkeys, an anaconda, frogs, fish and birds and African forests for gorillas.

All of the work is done with a watchful eye on the animals and local landscape, too. “We ask, ‘Is this the ideal condition for our trees?’” she says. “We have beautiful oak trees here, and we’re cognizant of all the soils and the roots — and the impact that construction might have on these trees and their longevity.”

Sustainable design and construction were incorporated into the South American exhibit, which Tang oversaw as project manager. Elements included solar tubes to bring natural light into animal bedrooms, natural ventilation where possible and closed-loop water filtration systems. Additionally, the team specified thermally modified ash and changed its wood procurement practices for future projects instead of using a dense Brazilian hardwood to preserve habitats for the wildlife counterparts of the zoo’s animals.

Architects have the responsibility to think not just about those who use a space, but the ways that the construction materials may affect others or the world more broadly. Sometimes, says Colman, an architect may have a responsibility not to give clients what they want because of the environmental or ethical considerations that might not be apparent on the surface.

For example, says Colman, a client might want teak flooring in a building because it’s durable and beautiful. “But as an architect, I might say no, because it’s going to come from a rainforest, and it might come from slave labor,” he says. “There’s often a sense that when people are building their own spaces, they have the right to make every decision, but they forget about the public consequences of those decisions.” An architect is charged not to forget those effects.

Finding the right balance among all of the different obligations and desires of a space’s users and the world around it requires architects to think not just about achieving a big vision, but also carefully deciding among the many choices that lead to a finished structure. “For every one decision most people think about, there are another 99 that architects think about,” says Colman.

Go Beyond the Moment

Carlos Jiménez is a professor of architecture at Rice.

In an age of immediate gratification and infinite disposability, architecture offers a tantalizing opportunity to create something that endures.

For Jiménez, the idea of endurance is about more than just creating a physically durable structure; it’s about creating a place that remains relevant and meaningful over time. “How does [a structure respond to] fashion changes, to economic shifts, to changing social mores?” he asks.

For example, Houston’s 35-year-old Menil Collection is a building he admires for its architectural endurance: a simple design, meticulously maintained and cared for. “I love the way the building sustains its vision. There is great dignity and power in that,” he says.

Creating a building that endures requires tenacity. It also often demands a focus on simplicity, which can allow for the complexity of a changing world to flourish around it.

The result of enduring work — whether the structure is a humble house, a bustling public space or an awe-inspiring cathedral — is an ability to evoke a feeling of well-being. “[Good] architecture makes one feel alive, immersed in the amazing experience of the world,” he says. “It makes one feel that someone cares.”

Pursue Greatness With Others

Juan José Castellón is an assistant professor of architecture at Rice and a founding partner at xmade, a firm focused on the research, design and materialization of contemporary buildings. Amna Ansari is a visiting critic at Rice and partner at UltraBarrio, an architecture and urban design practice.

Take a moment to truly experience the room you’re sitting in right now. Is beautiful light filtering through a window, or do you notice a picturesque view? Do you enjoy walking across the room without shoes because the floor is smooth and warm?

These are decisions architects think about — and work with many other experts to achieve. “The architect might talk to an engineer or an industrial partner to create a structural solution, the right air conditioning systems, or to use certain materials and colors for the flooring,” says Castellón. “[Engineers] might conduct some analysis and calculations, and we might collaborate to make sure a space has a certain quality,” he says. “As architects, our job is to build common ground for collaboration.”

Castellón compares the work of architecture to that of an orchestra conductor. A conductor must know about each instrument, the music and how to make the most of everyone who has their eyes on the baton.

By the same token, architects must have a broad understanding of a range of conceptual ideas and technical concepts. They must be open to the expertise and experience specialists can bring. “We must have the capacity to communicate ideas and coordinate [people and projects] harmoniously to build something,” he says. You might never consciously notice all of the details that make for a pleasing experience, but they are the result of countless collaborations. “The final goal,” Castellón says, “is you being safe and comfortable in your place.”

Ansari, meanwhile, sees the value of collaborative work not just at the level of a building, but at the level of a city. Many specialists bring exceptional expertise to one area but could also benefit from a slightly wider view. “If someone is focused on the technical aspects of sidewalks and accessibility, that’s great,” she says. “But are there ways that they might integrate that idea into a larger public amenity, like a set-back zone for a community market? Could the sidewalk become part of a connection to a trail that leads people to a park?”

Such visionary thinking was a big part of her firm’s recent work on a transit environment programming catalog for the Metropolitan Transit Authority of Harris County (METRO), a project that helps an array of different departments and stakeholders see how their work might integrate with others working on related projects. Zeroing in on the opportunities of collaborative work, says Ansari, offers a way to bring attention to real problems — and to harness opportunities that might otherwise go unnoticed. Cities become much more than the sum of their parts when they integrate ideas linked to ecology, safety and equality into the places their residents use each day.

“Thinking like an architect,” she says, “is about crafting a better future.”

Ask People What They Want but Give Them What They Need

Pyline Tangsuvanich earned a Bachelor of Arts in 2014 and a Bachelor of Architecture in 2016. She is a design studio manager at Cottage, a startup that focuses on accessory dwelling units.

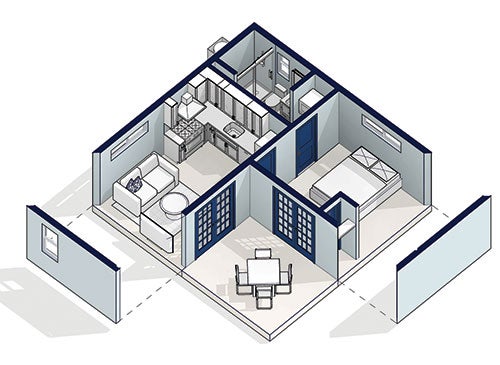

When homeowners come to Cottage to get help building an accessory dwelling unit (ADU), sometimes known as an in-law unit, Tangsuvanich says they often start with a vague idea. “They’ll say, ‘I want an efficiently laid out ADU for my aging-in-place parents,’” she says.

backyard. At the home-owners’ request, the ADU has a deck overlooking the creek to maximize outdoor views.

But getting from an intention to a real-life structure requires architects to dig deep with their clients on questions that boil down to “why” and “tell me more.” Architects ask these questions in ways that get refracted and illuminated.

For example, says Tangsuvanich, architects might probe more deeply into some of the common problems they see and specific concerns of a client — not just their stated goal. “We might say, ‘Do you want it to be space efficient so your mother can reach all the appliances in the kitchen without struggling? Are the heights of the counters something we should keep in mind?’”

While achieving specific aims may require quite technical solutions, they spring from a place of deep empathy for the needs of the people who will be using the space. “When you can see the world from someone else’s point of view, you can develop a solution that keeps their concerns and goals in mind,” she says.

See the World From a New Perspective

René Graham, who earned a Master of Architecture in 2010, is a former design principal and CEO of LaurelHouse Studio and the founder and CEO of the startup Renzoe Box.

When Graham was in architecture school, she learned the value of rethinking everything. “One of the things we did was to take a floor plan drawing and misread it as a section cut of a building,” she recalls. “When you do that, you become much more informed about the qualities of that space and how you could occupy it. As architects, we learn that the way something is currently isn’t necessarily the best solution. We assume that there are maybe 30 other approaches [to solving a problem].”

Graham’s belief in the value of finding a new perspective informs much of her work at Renzoe Box. The company creates modular makeup boxes that use flexible pods to combine products from any of dozens of brands into a single, cleanly designed palette. To create the kind of highly customized product she knew people wanted, she had to disregard decades of rigid design and manufacturing sequences commonly used in the beauty industry. Instead, she re-imagined an entire supply chain process.

While she recognizes that her approach isn’t the path of least resistance, she also sees her background in architecture as an asset to bring to the challenge. “As an architect, we learn to think through things, to design and then build them — to actually bring them to life and into physical reality. You don’t have to accept the status quo.”