Now Reading: Faculty Books

John S. Chase — The Chase Residence

David Heymann ’82 and Stephen Fox ’73

University of Texas Press, 2020

Modern architect John Saunders Chase Jr. was ahead of his time in nearly every way. In 1952, he became the first African American graduate of the University of Texas School of Architecture; two years later, he became the first African American to be registered as an architect in Texas. And when he designed and built a home for his family in Houston’s Oakmere neighborhood in 1959, it was the city’s first modernist house with a true interior courtyard, write David Heymann and Stephen Fox.

In “John S. Chase — The Chase Residence,” Heymann, an architecture professor at UT Austin, and Fox, an architectural historian and lecturer at the Rice School of Architecture, trade off in two essays about the Chase residence itself and Chase’s architecture more generally. Chase and his wife gravitated toward Houston as a place to live and work because it offered more economic opportunity than other Southern cities, although still systematically segregated. And while segregation meant that Chase was limited, in the 1950s and 1960s, to a “small-town, community focus,” Fox writes, that focus expanded when legal segregation was dismantled in the later 1960s. Then Chase began to receive public commissions from Harris County and the city of Houston. He designed a number of jaunty, ebullient public buildings, including libraries, health centers and a fire station, along with several impressive buildings on the Texas Southern University campus. “Chase’s buildings embraced a future that he was determined should be better than the past,” Fox writes. — Jennifer Latson

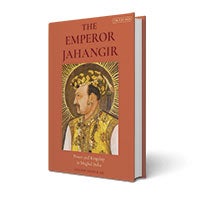

The Emperor Jahangir: Power and Kingship in Mughal India

Lisa Balabanlilar

I.B. Tauris, 2020

The intrigue, violence and debauchery that characterized Emperor Jahangir’s ascent to the throne could have been a “Game of Thrones” plot. The fourth leader of the Mughal Empire, Jahangir was eclipsed in fame by both his father, Akbar the Great, who extended the empire’s reach across the Indian subcontinent, and his son, Shah Jahan, who would go on to build the Taj Mahal. His own insecurities may have exacerbated the cruelty that marked his path to the throne, which entailed, among other things, the castration and public flaying of disobedient courtiers, a brutal elephant fight, and the murder of his father’s closest friend and confidant.

But there was more to Jahangir than brutality, as Rice historian Lisa Balabanlilar’s new biography demonstrates. Once enthroned in 1605, he softened some of his hard edges — although no one could ever describe him as a softie. “To be sure, it was a violent age and the emperor was not exempt from the standards of the time,” Balabanlilar writes, before describing how Jahangir punished a thief by having him torn apart by dogs.

The emperor was also an adept politician and a supporter of the arts who helped usher in a golden age in Mughal painting. He was a surprisingly thoughtful memoirist as well. Balabanlilar draws extensively from Jahangir’s diary, in which he recorded the events of his reign along with intimate musings on his life, including his struggles with alcoholism and opium addiction, his love for his family, his passion for hunting and his anxiety over establishing the legitimacy of his rule. — J.L.

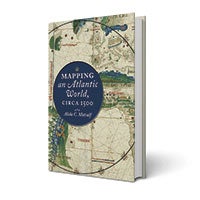

Mapping an Atlantic World, Circa 1500

Alida C. Metcalf

Johns Hopkins University Press, 2020

The moment when the “Atlantic World” first appeared on European maps marked a sea change in world history — literally and figuratively. After 1500, “people, plants, pathogens, products and cultural practices” began crossing the Atlantic Ocean, drastically altering life throughout Europe, Africa and the Americas. “Why was so much invested so quickly in exploring, developing, and risking lives and fortunes in the distant lands of the western Atlantic?” asks Alida Metcalf, the Harris Masterson Jr. Professor of History, in “Mapping an Atlantic World, Circa 1500.”

“So many of the supposedly inexorable events depended on new and startling decisions, such as the willingness to cross the ocean, the visualization of sources of wealth in places known only recently, the desire to create religious missions in unfamiliar regions, the belief that colonies could thrive at great distance, or the eagerness to invest in unpredictable and untested enterprises.”

Metcalf argues that one explanation for the sudden eagerness to jump on the Atlantic bandwagon lies with the early maps that helped explorers, evangelists, traders and colonizers envision an interconnected Atlantic World. Illustrated with 50 historical maps, Metcalf’s book demonstrates how early modern cartographers became agents of change who shaped the course of centuries to come. — J.L.

Leadership Reckoning: Can Higher Education Develop the Leaders We Need?

Thomas Kolditz, Libby Gill and Ryan P. Brown ’93

Monocle Press, 2021

In a world increasingly chock-full of leadership development programs, the Doerr Institute for New Leaders stands out because of its data-driven approach, focus on undergraduate students and commitment to improving leader development in higher education.

In “Leadership Reckoning: Can Higher Education Develop the Leaders We Need?,” the Doerr Institute’s Thomas Kolditz, founding director, and Ryan P. Brown, managing director for measurement, are joined by leadership consultant and executive coach Libby Gill in an exploration of leadership development initiatives focused on college students.

“Universities do not typically use evidence-based leader development strategies, nor do they measure the outcomes of their efforts to develop students as leaders,” the authors explain. “But by being measurement focused, we can ensure the most efficient system of development.”

In each chapter, the authors explore specific evidence-based techniques for leadership development in depth, showing how they contribute to students’ improved self-satisfaction and increased participation in leadership roles.

The authors also share concrete examples of the efficacy of the Doerr Institute’s four principles: leader development is a core function of the university; use evidence-based techniques; employ professional leader developers; and measure outcomes ruthlessly. At Rice, results are impressive: between 30% and 40% of undergraduates take part in Doerr leadership programs throughout their four years. — Mariana Nájera ’21