The Other Ellis Island

A 1907 guide for Jewish immigrants illuminates a fascinating chapter in Texas history.

By Katharine Shilcutt | Photos by Jeff Fitlow

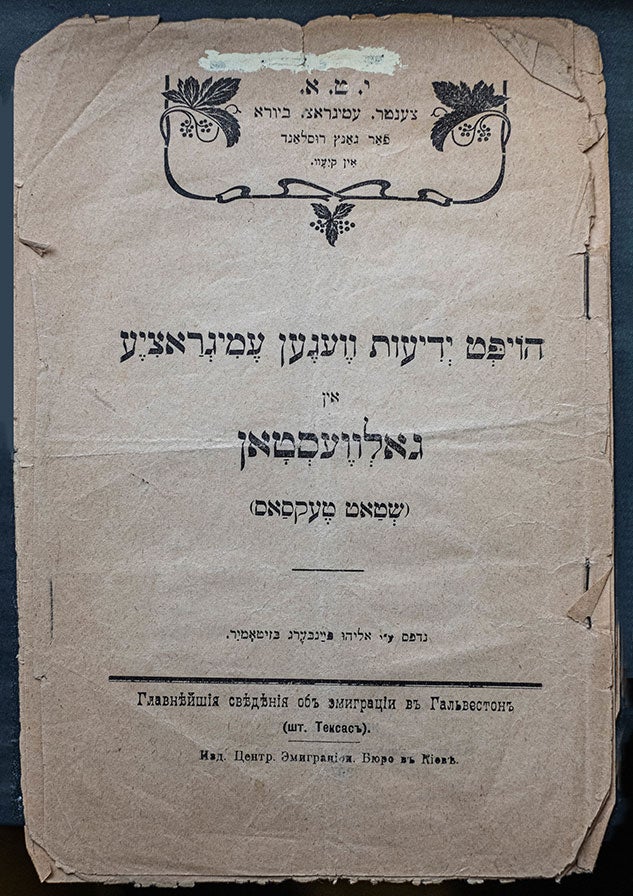

Most of the 10,000 Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe who arrived as part of the Galveston Movement between 1907 and 1914 fanned out across Texas and the rest of the nation. As they settled into new lives, mementos occasionally sent from back home reminded them of their difficult decisions to leave the Old World behind. Some artifacts, like a rare guide to the immigration process obtained last year, can be particularly revealing.

Located in Fondren Library’s Woodson Research Center, the Houston Jewish History Archive (HJHA) contains documents, testimonials and objects that illustrate the complex history of the Jewish community in Texas. One of its newest additions is a pamphlet obtained by Joshua Furman, HJHA’s director, from a rare Judaica book dealer in New York City. It is one of only two known to exist, printed in 1907 in Ukraine, mostly in Yiddish.

The pamphlet was revealed to be a guide to Texas — home to 20,000 Jews at the time — that was remarkably accurate. It described the jobs available in various Texas cities, the Jewish populations and institutions found there, what to expect upon arrival at the Port of Galveston and honest assessments of the weather: “Except for its southern section, its climate is good for your health, especially in the winter months.”

For Furman, it was a tremendous find. “Now we have the document that would have convinced people who live in a shtetl, in a small village, in Eastern Europe in 1907 … to try to entice them to make this incredible journey,” he said.

The Galveston Movement had an outsized impact on the Jewish diaspora in the U.S. It all started because a wealthy philanthropist from New York City, Jacob Schiff, recognized the need to settle Eastern European Jews in the heartland of America, where it was less likely they would be targeted by xenophobic opponents of immigration. Schiff’s guide illustrates the path across Eastern Europe taken by thousands of Jews that led them to Germany and then Texas, which eventually allowed them to take trains to towns as close as Marshall and Temple and to states as far away as Rhode Island and California.

For Furman, the pamphlet will help shed even more historical light onto the journeys these men, women and children decided to undertake. “What did they think they were getting into?” Furman said. “Right now, we have some information about that — we’ve got some memoir literature, some newspaper articles in the American press — but this is one more piece of the puzzle that we didn’t have before.”