Nature's Language

Natasha Bowdoin's Creativity Blooms

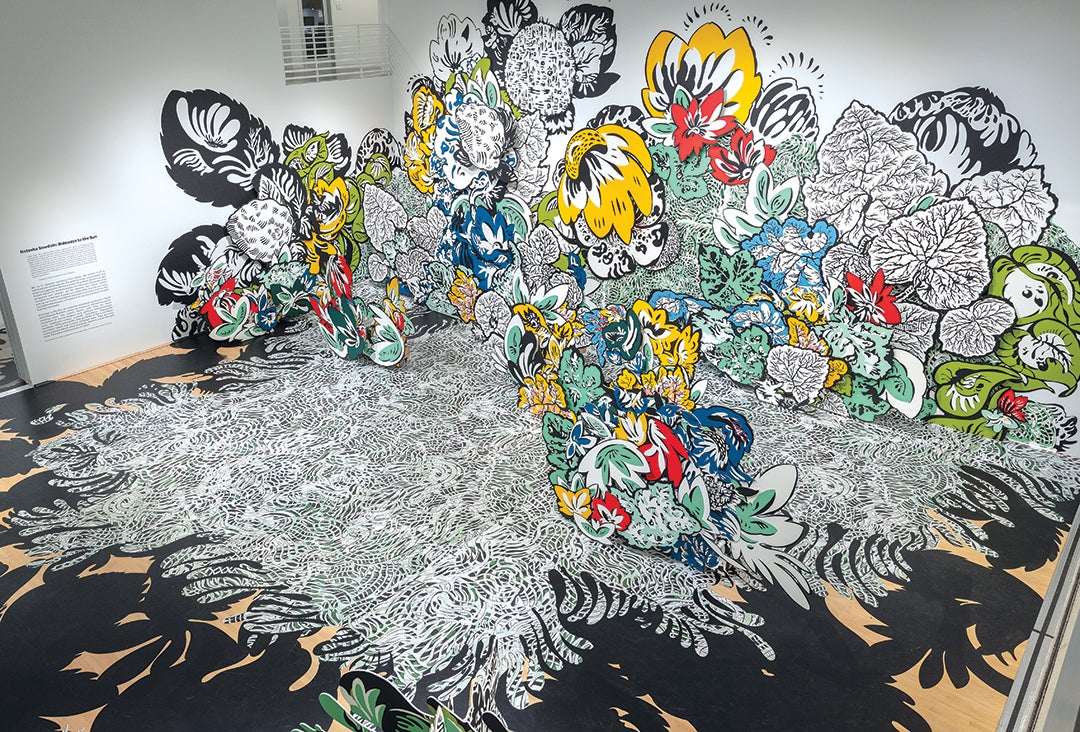

In the massive Central Gallery at Rice’s Moody Center for the Arts, gigantic fun house images of flowers, leaves and vines entwine visitors within a landscape that seems barely natural. Garish greens, yellows and reds splash across the walls, stretch toward the two-story ceiling or escape the space into the nearby halls. Some of the painted and cut out drawings are mounted on stage carts, ready to be rolled away and reoriented to performances inspired by artist Natasha Bowdoin’s creations.

For a visitor, the effect is one of being dwarfed by an overgrown, beautiful and somewhat menacing tangle. If nature is a language, as a line in a song by The Smiths goes, the language employed by Bowdoin shouts, entices and warns.

“It’s a kind of positive way to think about human insignificance in relation to nature,” said Bowdoin, an assistant professor in visual and dramatic arts at Rice, whose collage-based works have been exhibited widely over the past decade. “The scale is meant to overpower the viewer, reorienting them to my natural world.” The bold colors she employs at large scale are “playful and fun, but also a little bit too much, almost poisonous.”

Bowdoin was invited to create this site-specific work for the Moody by Alison Weaver, the Suzanne Deal Booth Executive Director of the Moody, as part of a curatorial focus on ecology and the environment.

From Victorian floral arrangements to trips to the moon

Bowdoin’s installations draw from myriad inspirations — cartoons, 19th-century scientific illustrations, the language of transcendentalism, textile prints and, intriguingly, lo-fi special effects in films such as the endearing “A Trip to the Moon” by French film director Georges Méliès.

While her current work interrogates the relationship between people and nature, this particular piece grew out of her interest in the “language of the flowers,” a Victorian practice that used floral arrangements as a secret language. “Flowers had specific meanings assigned to them, and floral dictionaries were produced so that one could become fluent in the vocabulary.

Nature is a language, can't you read? — "Ask" by the Smiths

You would arrange your bouquet to convey a particular message your recipient would then read in the flowers themselves,” Bowdoin said. “Often these messages expressed sentiments not deemed socially acceptable to speak out loud at the time, hence why they needed a floral disguise.” So Bowdoin set out to create her version of a less-than-subtle “decoder bouquet.”

“There’s a long symbolic tradition of the feminine and the floral being framed as representative of one another. I think that degrades both of those things — both nature and the feminine,” Bowdoin said. In these “loud,” larger-than-life landscapes, Bowdoin subverts conventional and historic ideas about the feminine and the floral in efforts to disentangle them from old meanings.

At an artist talk this spring, Bowdoin was asked about what secret message she may have included in her flowers. She thought about it for a while. “I think my message is ‘don’t mess with me,’” she laughed.

Transcending Transcendentalism

“Sideways to the Sun” not only subverts the relationship between the feminine and the floral, it also references writings by transcendentalists, especially Ralph Waldo Emerson’s 1836 essay on nature. “The whole notion of transcendentalism is the idea that the divine, however you choose to define it, is readable in nature,” Bowdoin said.

One of the most visionary ideas in Emerson’s essay is called the “transparent eyeball.” It’s a concept and an image that resonates deeply with Bowdoin. “He was arguing for permeability with the world,” Bowdoin said. “Nature is you and you are nature. There’s not such a distinct separation between the two,” she said.

Bowdoin, who grew up in rural Maine, connects with transcendentalist thinkers through her New England roots as well. “My family members are all fishermen or stonemasons. They learned an intimate understanding of nature, its beauty and its threat, pretty early,” she said. “Even when I try to get away from nature in my work, it always creeps its way back in.”