13 Ways of Looking at Creativity

Every day, we see the spark of imagination and invention in Rice’s classrooms, labs, studios and galleries — crossing disciplinary boundaries and generating new ideas and solutions. This year, creativity is a theme of lively classroom conversations and lecture series. We picked 13 ways that Rice faculty and scholarly guests are studying, teaching, expressing or nurturing the creative force that is available, surprisingly, to us all.

Bend, Break, Blend

If you know where to listen, you can hear the creative process unfold right before your ears. That’s especially so if you have a guide like composer Anthony Brandt, a professor at Rice’s Shepherd School of Music.

Along with neuroscientist David Eagleman ’93, a former Rice colleague who is now at Stanford, Brandt researched and published a book about the neuroscience of creativity called “The Runaway Species: How Human Creativity Remakes the World.” Charmingly illustrated, the book is full of head-spinning examples of humans’ drive to create and the cognitive strategies underlying the creative impulse.

In fact, one of the basic tenets of their research is that imaginative leaps do not spring from eureka moments, but are “the latest branches on the family tree of invention,” they wrote. “Humans are continually creative: Whether the raw material is words or sounds or sights, we are food processors into which the world is fed, and out of which something new emerges.”

This year, Brandt has served as a maestro of creativity in classrooms at the Glasscock School of Continuing Studies and the Moody Center for the Arts, as well as through planning and participating in the annual Scientia Lecture Series. In fact, in Scientia’s kickoff lecture, Brandt took his audience through a tour de force explanation of how humans imagine and create new ideas.

“Imagination can be thought of as predicting something that has never happened before and creativity as making it come true,” he said to a packed auditorium. So where do new ideas come from? “They evolve from prior experience,” Brandt said. “Creativity is a process of derivation and extrapolation. We remodel what we know.”

Brandt and Eagleman propose an elegant framework for how the brain evolves new ideas — in just three basic cognitive strategies: bending, breaking and blending.

In bending what we know, “an original is twisted out of shape or transformed in some way.” A simple example: fonts.

In breaking, “a whole is taken apart and something new is made out of some or all of the pieces,” Brandt said. Imagine Julian Schnabel’s plate paintings.

And in blending, “two or more sources are merged,” like in the imaginative superhero, the Wasp.

To more fully illustrate “the three B’s” of cognitive strategies, Brandt enlisted musical accompaniment — and a fourth “B.” In Beethoven’s genius, Brandt explained, we can see and hear the strategies of bending, breaking and blending. “And that’s where his creativity is most exposed — and we can all hear it.”

The radical notion of this theory is that the same elements available to Beethoven are available to everyone. Creativity can be taught and learned — or at least practiced. This has become a core tenet of Brandt’s teaching, especially in courses like MUSI 379: Creativity Up Close, which he taught this spring in both the Glasscock School and for Rice undergraduates. To help Brandt explore creativity as a “universal feature of human cognition,” guest lecturers from engineering, history, business, psychology and the arts brought their own examples of imagination at work to the classrooms.

Back to music, and Brandt’s home turf. “We all have a bit of Beethoven in us. In our daily lives, we bend, break and blend what we say and do, to engage each other and keep ourselves alert,” Brandt reminded the audience. “Beethoven’s music is a distilled version of all that. That’s one of the reasons why we feel we get wisdom or insight from listening to it. It helps us understand ourselves and how we relate to the world.”

HEAR IT

“Beethoven’s inventiveness is amplified by the need to hold our attention. He’ll deploy strategies we’ve just heard and many others to keep us involved. And from one work to the next, he’ll constantly switch up how he applies these strategies, because of course if his means of holding our attention become too predictable … that defeats the whole point,” Brandt said.

“Let’s listen to the first movement of Beethoven’s String Quartet Opus 59, No. 1. He’ll spend the first part of the movement introducing a series of themes, which he’ll then remodel in front of our ears. ”

Listen here.

Special thanks to Shepherd School of Music students Samuel Park and Jacqueline Audas, violin; Sergin Yap, viola; Katherine Audas, cello.

That's Genius

What do geniuses have in common? Is the mind of an artistic genius the same as a scientific genius? Can you (or I) learn to be a genius?

These are some of the questions that drive the decadeslong research of Dean Keith Simonton.

A distinguished professor emeritus of psychology at University of California, Davis, Simonton has written extensively on the subject of identifying creative genius, sifting through theories, data and lore to pinpoint the common features of the gifted mind. His work seeks to explain how the creative genius produces a seminal work, and he argues that “while such breakthroughs often seem to appear in a flash, the underlying mechanisms are likely to be much more orderly.”

In April, Simonton came to the Moody Center to talk about his research. Building upon the work of psychologist Donald Campbell, Simonton developed a theory that explains the process of highly creative thought.

It was Campbell who named the theory blind variation and selective retention (BVSR), but Simonton spent 25 years testing and expanding the central premise — that the creator repeatedly engages in a trial-and-error

process before the breakthrough moment.

The theory highlights two specific ways of thinking: superfluity and backtracking. Superfluity simply means generating a variety of ideas without concern about their eventual usefulness. Backtracking, then, refers to the process of returning to an earlier idea or approach after an unsuccessful creative attempt.

According to Simonton, the significance of BVSR is the ability to attribute specific personality traits, modes of thinking and developmental experiences to the creative genius. His research suggests that an openness to new ideas and participation in a range of interests is necessary to produce the variety of ideas required for superfluity. Looking forward, Simonton’s research asks if these characteristics can be cultivated or translated into predictive models of genius.

Mixing it Up

What makes a painting by 17th-century Dutch painter Johannes Vermeer distinctly recognizable? The intimate settings? The natural light and shadows? The exquisite details?

Most people would probably not answer, “the painter’s use of technology.” But art historians surmise that Vermeer employed an early version of the camera — called the camera obscura — to achieve some of these thrilling effects.

Alison Weaver, the Suzanne Deal Booth Executive Director of the Moody Center, recently shared stories about Vermeer’s use of the pinhole camera, Leonardo da Vinci’s engineering drawings and Edgar Degas’ groundbreaking compositions to illuminate the catalytic nature of the arts. As one of the guest speakers in the 2018–2019 Scientia Lecture Series, Weaver brought her expertise as an art historian, administrator and advocate for cross-disciplinary exploration to the topic of creativity.

At the Moody Center, Weaver is leading a robust program that fosters creative conversations and experiences that step across the lines of traditional academic boundaries. “We’re actively engaged in such questions as, How do art, science and technology relate to each other? ”

Now entering its third year, the Moody Center’s programming is leaning hard into that intersection. Through exhibitions, university classes, artists-in-residence programs, theater and dance performances, student workshops and other experiments, Weaver and her staff are creating opportunities for different fields to come together and be inspired to think differently.

For example, in their inaugural season, the center hosted German photographer Thomas Struth. His large-scale images of particle colliders, chemistry labs and NASA’s Johnson Space Center are both familiar and inscrutable. Struth’s image of the “Z-Pinch Plasma Lab,” a device that generates magnetic fields by producing fusion power through compressing plasma, is dazzling in its complexity, with elements of the familiar. “This is an example of how an artist’s vision of our technological university is feeding back into the cultural conversation about the dialogue between the man-made and the natural world,” Weaver added.

While heady topics such as plasma physics, space science and ecology are right at home on Rice’s campus, this robust connectivity with the world of art and humanities is something new. “We want to be a lab for creativity,” Weaver said. Like the groundbreaking artists of the past, these connections help us see the world more clearly — and with thrilling effects.

Failing Better

What do a giraffe feeder, an IV drip and a robotic arm have in common? They’re all recent Rice engineering design projects that were tested and refined using a process of rapid or low-fidelity prototyping.

In Rice’s bustling 20,000-square-foot Oshman Engineering Design Kitchen (OEDK), students work in teams to find solutions to a wide range of client-sponsored engineering challenges.

“The definition of prototyping is solving problems by creating physical or digital artifacts,” said Matthew Wettergreen ’08, who teaches ENGI 120: Introduction to Engineering Design. Last year more than 140 teams and clubs used the OEDK’s resources. “Rapid or low-fidelity prototyping is the best place to start when you have a physical idea you need to realize, because it’s low cost, the materials are readily available and it simulates the conditions that exist in places outside the U.S. where resources may not be as abundant.”

Wettergreen sees the seeds of innovation in materials commonly found in a kindergarten classroom — cardboard, tape, scissors and Play-Doh. “You can combine them in fascinating ways to represent objects, tell stories or even achieve function,” Wettergreen said. For the new engineering student who may not be proficient with a lathe or laser cutter, such materials present a low barrier for design.

“One of the things you need to bring to prototyping is that there are no wrong answers,” Wettergreen said. “Everything you build is a stepping stone to the next idea. Discarded solutions help you to arrive at the selected solution.”

This year, for example, a freshman team was working on a way to identify when hearing protection is recommended around the OEDK machines. They developed a series of prototypes that would alert users with colors and lights when a machine was too loud. They went through four or five different versions of these prototypes before settling on a simple geometric design for the case and a series of flashing lights to alert the user to use ear protection.

“The reason that prototyping is an effective strategy to solve problems in a team is that it brings the ideas that people have in their heads into a physical space, allowing them to be discussed, compared and explored,” Wettergreen said. In team projects, getting on the same page is crucial to success. The proof is in the prototype.

Crawl, Walk, Run

Comics belong in college, artist Christopher Sperandio contends. They’re educational, artful and powerful vehicles of cultural criticism — not to mention entertaining.

An associate professor in the Department of Visual and Dramatic Arts, Sperandio embraces comics both as mass culture consumable and as works of artistic integrity.

In his popular course, ARTS 230: Comics and Sequential Art, Rice students learn the history of comic books — “one of the few truly American art forms” — while also producing their own sequential stories. The students who are drawn to the course are generally familiar with superhero-themed comic books from the DC and Marvel universes, popular graphic novels like “Maus: A Survivor’s Tale” and Japanese manga — but few have tried their hand at creating their own.

Over the course of the semester, students explore narrative topics in gradually more complex formats: from simple three-panel forms to three pages and then to a final project — a 16-page original comic. This “crawl, walk, run” approach helps develop the creative process, especially for students who’ve been told they are not creative, Sperandio said. Some work in digital software, but most are inclined to pick up a pencil and pen to draw their creations.

Freshman Catherine Hettler explored social justice advocacy in her first hand-drawn panel comic, which she described as sort of a PSA about the Women’s March. “It encourages people to look into the march and take a stand.” This class was one of her favorite first-year experiences at Rice. “Because we had so much freedom in what we could write about in our comics, it was open to whatever your interests are outside of art. I definitely learned a lot about art and composition, but also storytelling,” Hettler said.

A key teaching resource for the class, Sperandio said, is the Comic Art Teaching and Study Workshop, a repository of comics, original comic art and books on comics located in a former conference room in Sewall Hall.

“Having this comics resource at hand is crucial in teaching as it opens the subject to the students. In closely analyzing the original art, students can unlock how the things were made,” he said. “I try and get them to think about how do we do this.”

Improv & Tradition

As in daily life, improvisation in jazz means the spontaneous invention of something new. To the audience, this think-on-your-feet creativity may sound effortless — a talent channeled from some mysterious source. Think of the dazzling solos of jazz giants like alto saxophonist Charlie Parker, tenor saxophonist John Coltrane, singer Ella Fitzgerald or pianist Thelonious Monk, to name just a few.

At Rice, students learn and practice the art of improvisation as well as arranging and composing from jazz instructor and saxophonist Danny Kamins. A Houston native and graduate of the Houston School for the Performing and Visual Arts, Kamins directs the Rice Jazz Ensemble and Jazz Combo (sometimes called Jazz Lab).

Students of any major can sign up for these band classes. “Just about my whole saxophone section is engineering, computer science and poli-sci majors,” Kamins said, noting one exception. “One of the saxophonists is a Shepherd School of Music pianist.” Like the MOB, the Rice jazz bands are open to Rice alumni and to community members as well.

Improvisation, while wholly original, takes place within a musical context — no matter the musical instrument, the notes build on existing themes and structures. The students steep themselves in jazz tradition by listening to classics, and Kamins introduces them to artists who play the same instrument they do.

“Larry Slezak did that for me,” recalled Kamins, who spent his freshman year at Rice before transferring to Oberlin College. Slezak was an instructor in jazz studies at Rice from 1980 to 2016 and a widely respected musician and teacher.

“I was a baritone sax player, and I knew nothing about bari sax players. He had me listen to Gerry Mulligan, Pepper Adams and Harry Carney. It educated me and gave me a historical context on how the instrument worked,” said Kamins, who works to pass along the lesson. To develop students’ confidence and skill in improvisation requires practice and practice — playing with the bands, with Kamins or with the help of accompaniment software.

In the combo band, “everybody has to solo,” he said. Kamins works to create an atmosphere that is a change of pace from their main academic work.

Border Lines

“My creative process always starts with research,” said Veronica Gomez ’19, a recent Rice architecture graduate. While designing her master’s thesis, she studied the history, people, natural terrain, and political and social issues of the Mexico-United States border.

She then funneled her findings into a series of designs that reflect the complex dynamic along the border. Her starting point was a piece titled

“Claiming the Line,” a foldout, 14-foot-long stitched canvas map that details border infrastructure, historical changes, ongoing transactions and even the interactions necessitated by daily living along the divide.

“I am from Mexico, so this topic naturally interests me,” Gomez explained. Like her adviser, Dawn Finley, a Rice associate professor and director of graduate studies, Gomez is particularly interested in fabrics. One striking feature of the canvas map is its ability to compress and expand. When opened, the viewer sees the border as a whole, but the compressed map zooms into specific instances of border life.

Gomez came to see the border “as a region rather than two countries divided,” and in response she designed a second piece, a building that would “embody the dual character of the border.”

Adorned with different facades facing each country, the building would be a space for humane communication between individuals living on either side and a repository for oral histories of border life.

While Gomez’s designs begin with a thorough examination of her subject, creative progress comes through translating her knowledge into a series of diagrams — often lines and circles that are comprehensible only to Gomez herself. “I identified specific spots along the border and created diagrams that captured the minimal essence or idea of these spaces,” Gomez explained. “This process helps me to understand how things work. From the diagrams, I can then reshape or extrapolate new designs.”

A Family Story

How do you distill and communicate the essence of a person? As a guest lecturer in Anthony Brandt’s Creativity Up Close class, Anne Chao ’05 challenges students to inject creativity into the work of oral history.

Chao, co-founder of the Houston Asian American Archive, is engaged in the work of collecting oral histories that detail the contribution Asian-Americans have made to the Greater Houston area. So far, the archive has amassed more than 200 stories. The assignment for Brandt’s students was to choose a subject, conduct a five- to six- minute interview, and make a presentation that succinctly and creatively conveys the substance of the individual. “We were pushing the students to think outside of the box while staying true to the idea and purpose of oral history,” Chao explained.

Chao’s favorite project depicted an interview with Christine Hà, a best-selling author and blind chef who took home top honors in season three of the MasterChef competition. “The team dimmed the lights in the classroom to simulate blindness,” Chao remembered.

“Then they gave us three food samples that corresponded with important moments in her journey.” The sample foods were a peanut butter and jelly sandwich — one of the first “meals” she made after losing her sight; an apple pie — a symbol of a pivotal moment on MasterChef; and a cup of Vietnamese coffee — which represented her heritage. “In just a few minutes,” said Chao, “they communicated the story and spirit of Christine.”

Chao’s own work at Rice often focuses on amassing the historical creative output of individuals or groups. She oversees students who are collecting recipes alongside geographic and familial details from oral history subjects. Chao is also interested in tracing the growth of the civic organizations of immigrant communities, identifying ways these populations banded together to ensure mutual success. “Pulling together different elements of history into functional forms,” Chao said, “is in itself a creative endeavor.”

Plié and Lead

In the downtown studios of the Houston Ballet, young dancers spend their days leaping and stretching, bending and spinning. In the ballet’s professional training program, they learn to discipline their bodies to speak the graceful language of dance. Soon the dancers, ages 14–19, will have another muscle to train: They’ll receive lessons in leadership in collaboration with the Doerr Institute for New Leaders at Rice.

But what does leadership have to do with the elegant agility of dance? Everything, if you ask Tom Kolditz, the institute’s founding director. “The arts, to me, are really in need of enhanced leadership,” he said, and that’s because creativity and leadership are often put in separate silos.

Jim Nelson, executive director of the Houston Ballet, met with Kolditz last year and learned about the Doerr Institute. “It got me thinking: How fantastic would that be, if we at Houston Ballet could expose our younger dancers in the professional track of our school to leadership training, so we are also playing a role in developing the dance leaders of the next generation?”

The dancers will likely receive training much like what’s provided for Rice students: one-on-one or group coaching to help the dancers improve their personal effectiveness, from resolving conflicts to inspiring others.

“Most people in leadership roles in the arts got there by being good artists, not good leaders,” Kolditz said. Society encourages people who excel in creative fields — dance, music, writing, the visual arts — to be independent and somewhat solitary. When they’re faced with leading a group or an organization, they often don’t have the background they need.

While it’s important for artists to have leadership skills, it’s just as important for leaders to have expressive, artistic skills, Kolditz said. Good leaders can see beyond the day to day and develop a vision for the future.

“Creating a vision is an important leader ability, and it’s very artistic,” he said. Like those young dancers in Houston, leaders have discipline, flexibility and a sense of the extraordinary — and they can inspire others to help them make it come alive.

Creativity Killers

The internet is packed with artful pictures superimposed with concise, insightful quotes about creativity from Teresa Amabile, a creativity scholar at Harvard Business School. One of the best — “One day’s happiness often predicts the next day’s creativity” — seems like foolproof advice for both managers and creatives.

Amabile, a guest lecturer in the “Creativity Up Close” lecture series this spring, has dissected workplace creativity and constructed a model for ideal creative conditions. Her theory of creativity includes three components internal to the individual that are necessary for creative work.

The first two, expertise and creative thinking skills, encompass the knowledge, experience, talent and perspective necessary to generate new ideas, theories or products.

But it’s Amabile’s third component — motivation — that is her biggest contribution to creativity theory. “What I’ve discovered in my research,” Amabile explained, “is that intrinsic motivation is essential for high levels of creativity.” Intrinsic motivation is the drive to do something because of interest, enjoyment or a personal sense of challenge. The opposite form of motivation is extrinsic, which denotes taking action because you have to, you are being forced or because you are working for a reward.

Focusing on workplace culture and team dynamics, Amabile also identified a list of “creativity killers.” These include expected evaluations, feelings of being watched, working only for a reward, competition, tight restrictions on how work can be performed and an undue focus on extrinsic motivators.

“What I’ve tried to do in my research is look at what business organizations and managers can do to relieve the work environment of these extrinsic constraints to allow people’s intrinsic motivation and creativity to blossom.”

Everyday Creativity

A playwright, lyricist and psychologist, James C. Kaufman’s professional and creative work explains why creativity matters — particularly why we should care about it, measure it and nurture it. For Kaufman, the practice and presence of creativity make life immeasurably sweeter.

Kaufman, a professor of educational psychology at the Neag School of Education at the University of Connecticut, theorizes that creativity is both a widespread phenomenon and critical to human development.

Rather than reserving the term “creative” for the favored few who produce globally acclaimed works of art or world-changing discoveries, he said, creativity is a label just as easily applied to the prosaic activities of everyday life — learning, problem-solving or making a junior high art project. In February, Kaufman kicked off the “Creativity Up Close” lecture series.

Kaufman’s “Four C Model of Creativity,” which he developed with colleague Ronald Beghetto, theorizes creativity as a trajectory. In doing so, his work effectively subdivides creativity into levels, intensities and magnitudes, and offers researchers a defined framework for situating creativity studies. The Four C’s range from mini-c, moments of meaningful insight, to little-c, which includes everyday creativity.

At the higher end, pro-c creativity designates work at an expert level, like publishing a paper or developing a scientific theory, and big-c is reserved for individuals who have changed the field in which they work, whose creation stands the test of time and who can legitimately be called creative geniuses.

In his lecture at Rice, Kaufman spoke to students about the role of creativity in the process of making meaning — emphasizing that all four C’s can make significant contributions. Modern theories of meaning tend to revolve around concepts of coherence, significance and purpose, and Kaufman contends that “creativity can lead you on a path to all three.”

Engaging in expressive writing, losing oneself in a creative task or leaving a creative artifact as a legacy all facilitate the formation of a comprehensible and meaningful self.

Creativity Myths

Creativity is Jing Zhou’s business. As the Mary Gibbs Jones Professor of Management at Rice’s Jones Graduate School of Business, Zhou studies the ways managers can foster creativity and innovation among employees. But the factors that promote — and inhibit — creativity are often the opposite of what you’d expect.

A. Conscientious employees need permission to be creative. Managers value conscientious workers, and rightly so: they’re determined, driven and high-achieving. But they aren’t always creative, especially in workplaces where conformity and self-control are prized and risk-taking is frowned upon. “Conscientious people are responsible, organized and they try hard, but we [Jennifer George, fellow Rice business professor, now retired] demonstrate that under certain conditions, those traits can be bad for creativity,” Zhou said. To liberate the creative impulses of highly conscientious employees, managers need to actively encourage flexibility and free thinking and to support them when they try something new.

B. Diverse teams aren’t always more creative. While diverse teams have the potential to be more creative than homogenous groups, they depend on inspiring, motivating and unifying managers — what researchers call “transformational” leaders — to actually unlock that potential. “Team diversity itself does not result in team creativity,” Zhou said. “Rather, the leader needs to exhibit transformational leadership behaviors.”

C. Embrace bad moods and dissatisfied employees. Don’t overlook disgruntled workers, Zhou warned: They can be the source of a company’s most groundbreaking innovations. In a 2002 study, Zhou and George found that bad moods often produced good ideas — and vice versa. The reasoning? “Positive feelings serve as a signal that everything is going well,” they wrote. “Negative moods signal that the status quo is problematic and that additional effort needs to be exerted to come up with new and useful ideas.”

D. A little underemployment can be a good thing. When employees work beneath their capacity, they can get bored — but they can also get creative. Moderate underemployment can drive workers to redesign their jobs to better suit their skills, which can help both the worker and the company. (Large discrepancies between a worker’s ability and the work itself are bad for everyone, however.)

E. An ounce of prevention can be the death of creativity. As Zhou’s research shows, managers can stifle employees’ creative impulses if they focus too much on preventing harm and not enough on promoting innovation. Prevention- focused managers tend to be cautious toward new ideas, which they associate with danger. Managers are more likely to spot game-changing ideas if they have what Zhou calls “promotion focus”: a level of comfort with new experiences, which they approach with a sense of

adventure.

Homework: Variations On a Theme

Go back to school by completing this creativity exercise.

Classical musicians have mined the form of themes and variations to create enduring works of imagination. As a listener, think of Beethoven’s 33 Variations on a Waltz by Anton Diabelli, Op. 120 or Rachmaninoff’s Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini.

But riffing on a theme holds meaning for many musical styles as well as for the performing arts, literature, scientific research and daily life (as in recipes). Anthony Brandt has found that students respond to the idea of variations on a theme as a creative exercise. By using poems (instead of musical notes) as the source material, Brandt opens up the exercise to students of any major.

We invite our readers to be students again by participating in the “Variations on a Theme” exercise.

Here’s how it works.

Begin with a poem. We’ve reprinted “The Soul selects her own Society” by Emily Dickinson. Use this poem (or another of your choosing) as the source. Create four variations on the poem, with each one getting further and further way from the source.

Variation I. Employ your creative license to vary the language and meaning of the poem.

Variation II. Make your changes vary even more from the original.

Variation III. This variation may barely resemble the original.

Variation IV. This variation should break the mold of the original poem in some way.

Your variations are not limited to words, but can involve multimedia such as images and video.

The Soul selects her own Society (303)

by Emily Dickinson, 1830–1886

The Soul selects her own Society —

Then — shuts the Door —

To her divine Majority —

Present no more —

Unmoved — she notes the Chariots — pausing —

At her low Gate —

Unmoved — an Emperor be kneeling

Upon her Mat —

I’ve known her — from an ample nation —

Choose One —

Then — close the Valves of her attention —

Like Stone —

c. 1862

Looking for inspiration? Here’s what a few students in “Creativity Up Close” came up with for this assignment.

IS THERE ANYBODY OUT THERE

Senior Allison Rozich took as her subject a popular Tumblr meme and turned it into a spoken word poem. First, she recorded a lively reading of the original text.

“Gosh, but like we spent hundreds of years looking up at the stars and wondering ‘Is there anybody out there?’ and hoping and guessing and imagining … .”

Because her text was long, each of her variations was dedicated to a segment of the original. The addition of archival imagery and sound effects helped to move each variation further and further from the original. Her fifth and final variation breaks the mold with a transcription of the piece’s final 20 words in atomic notation.

Watch the video here.

HOUSE DRESS

Connie Do ’17 chose a one-sentence poem by Joseph Legaspi called “Your Mother Wears a House Dress” as her original text. It begins in a whimsical way:

If your house

is a dress

it’ll fit like

Los Angeles

Do created a video with hand-made drawings of a house followed by increasingly distorted voice and computer-generated images. Finally, there is just code for drawing a house and the word.

Watch the video here.

OCEANS, FORESTS, WORDS, EMOJIS

In our final example, Michael Galko, a student at the Glasscock School for Continuing Studies, uses a poem by Lawrence Durrell (1912–1990) as the base for variations on a theme. Here’s the original.

There is a great heart-break in an evening sea;

Remoteness in the sudden naked shafts

Of light that die, tremulous, quivering

Into cool ripples of blue and silver …

So it is with these songs:

the ink has dried,

And found its own perpetual circuit here,

Cast its own net

Of little, formless mimicry around itself.

And you must turn away, smile….

and forget.

Variation 1 transposes the poem from the ocean to a forest.

I. Fun (g) us

There is a great white cap on an evening forest Floor;

some regret in the sudden waning shafts

Of sun light that shine, tree-piercing,

Into pools rippling with moss and fern…

So it is with that birdsong:

the notes have died,

And found their own palatial surfeit here,

Cast their own spell,

A little, formless wizardry around hyphae.

And you must fold into yourself, shroom….

and sleep.

Variation 2 rearranges the words to deliver the same message.

Flat (ter) is

Forget the dried ink here.

An evening heart-break, silver shafts…

Cool blue songs, tremulous naked light

that has a sudden remoteness,

these ripples of great formless sea;

so it is in perpetual mimicry:

Found there is its own circuit, quivering

into and with it’s own little net

cast around and in the die of

of itself.

And smile you must,

and turn away…

Variation 3 rearranges the letters of each line to create a different poem.

Ferrous: A miner’s drunk evening

Hearth breaks even- eeeasing in a Terra giant

light that dies, quiver fool mute ruing,

slivers into bland ice fool ore pulp…

this white soot singes:

thee drink is had,

down its circuit perpetual an found here,

static’s went on,

self around it of little formless mi mi cry,

and you a musty, smite ur lawn….

forge an dts.

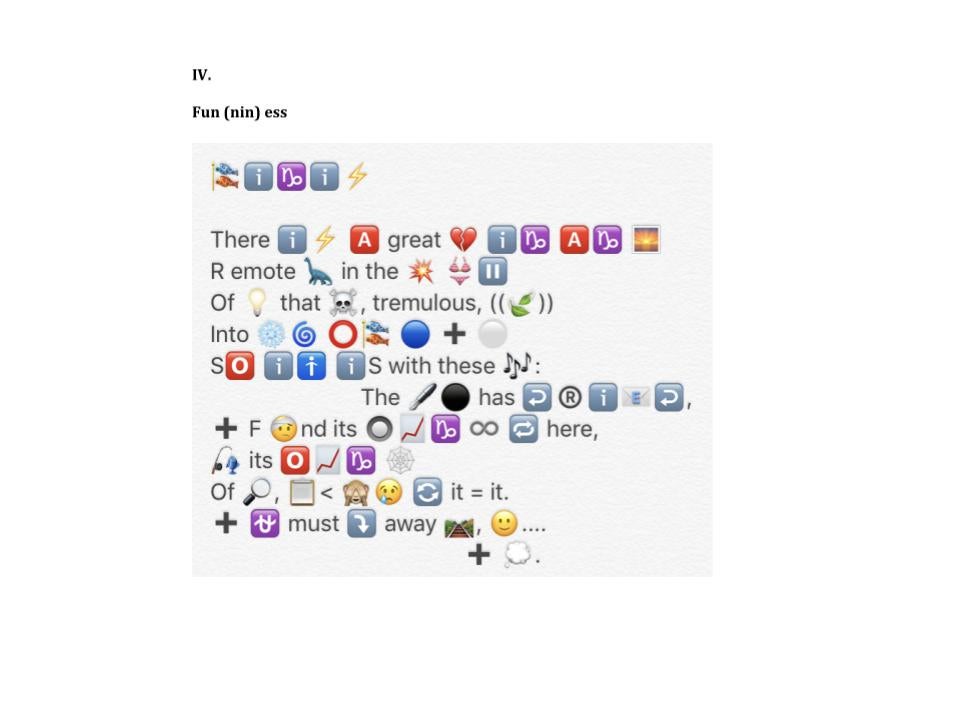

Variation 4 translates the poem into emojis.