This Authentic Life

In the spirit of springtime and new beginnings, we reached out to a half-dozen owls to tell us their stories of career and life reinvention. And we were delighted with the variety of responses. Individually, they may have little in common; collectively, they share a desire to seek and find a more authentic and satisfying life.

Spring 2017

MAKING MUSIC

After training as an architect at Rice, Mary Jane “MJ” Kwan ’10 joined a firm in Beijing, where she helped build large projects. Today, she’s still a builder, though on a much smaller scale, as a maker of violins.

Both jobs require a keen sense of design and space. The skills in digital representation and modeling that Kwan learned as an architect now help her document the exact shapes of rare instruments and visualize the geometry of violin bows.

Kwan has always liked to draw and to think in three dimensions. “When we were kids, one of my sisters and I would draw floor plans, trade them and imagine the spaces we created,” she said. Grand works of architecture always moved her. The study of architecture had seemed like a fit.

But working at a couple of different firms in Beijing was demanding and less creative than she’d hoped, Kwan said. Her work seemed disconnected from its results. “The culture of working from 9 a.m. to 8 p.m. did not encourage us to investigate how the people we were designing for actually lived,” she said.

However, living in China for the first time emboldened Kwan to be assertive enough to try new things. “You know the idea of America as the land of opportunity? When I was in China, when people had an opportunity, they really went for it. And so I learned to do that, too,” she said.

For example, there was a piano shop in the Beijing building where she worked. Kwan was a music lover with a classical piano and cello background who no longer had much time for music, but she did enjoy hanging out in the shop, playing the pianos and interacting with the owners and families passing through. “It was like a musical oasis,” she said — as well as a way to gain perspective about other people’s lives. She ended up joining an amateur orchestra in Beijing, where she performed a few piano concertos.

Those performances gave Kwan the final push to leave architecture and become a music teacher full time, teaching kids to play piano and cello. Teaching music lessons brought her back in touch with a pursuit she had dabbled in during her undergraduate days: lutherie, or the making of stringed instruments.

Teaching music lessons brought her back in touch with a pursuit she had dabbled in during her undergraduate days: lutherie, or the making of stringed instruments.

In one Rice class, she had learned to make musical instruments in order to understand what was involved in building a guitar factory. “That turned into a huge mandolin-making project,” Kwan said. Outside of class, she even made a bass guitar. “I didn’t find [lutherie] irrelevant to architecture at all. I like technical things, and I like design and I like working with my hands.”

She applied to the Chicago School of Violin Making, began studying there in 2013 and finished the three-year program last year. She anticipates soon landing work in violin-making or repair.

“I’m very grateful that I’ve been so scatterbrained — or that I’ve had so many interests and pursued so many things, because they do come together quite nicely,” Kwan said. Her craft lets her spend time on the analytical details she relished obsessing over as an architect; what’s more, “you can see what you’ve accomplished.”

A HIGHER CALLBACK

A Hollywood production lot may not have much in common with a synagogue, but Rabbi Oren Hayon ’94 saw each as a stage where stories come to life.

As an undergraduate at Rice, Hayon studied English for the same reason that he later went into the rabbinate. “I am drawn to, fascinated by, the alchemy of the written word,” he said. He focused on dramatic literature and the theater, working closely with Dennis Huston, now-emeritus professor of English, and directing, writing and performing with the Rice Players and BakerShake, the annual spring festival of student-acted and produced Shakespearean works. He also studied Renaissance drama and performance in England for a year.

Shortly after graduation, Hayon headed to Hollywood, to “get to the place where words became stories, and the place where stories transformed people and communities and lives.” There, he worked for a major entertainment production company, writing and doing production work as well as occasionally acting in and directing independent projects.

Over time, Hayon realized that “the people I shared my work with weren’t as enchanted by the process of crafting and delivering transformative stories [as I was],” he said. In fact, the people whose values most resonated with his own were outside the studios and in the faith community, where Hayon became more and more involved.

Eventually, the force pulling him to the faith community won out. He found himself looking forward to weekends, when he could work in the Jewish community and immerse himself in religious contemplation. “Once I realized that what I thought I always wanted was not what I wanted anymore, then the jump wasn’t painful at all,” he said. After five years in Los Angeles, he began rabbinical studies in Jerusalem.

“Once I realized that what I thought I always wanted was not what I wanted anymore, then the jump wasn’t painful at all,” he said. After five years in Los Angeles, he began rabbinical studies in Jerusalem.

His studies, first in Israel and then for four years back in the United States, renewed his love of academic inquiry and community service — “a combination of the head and the heart and the hands,” he said. He went on to serve in a synagogue in Dallas and then ran a Jewish student organization in Seattle. But he’s found his best match so far at Congregation Emanu El, the synagogue near Rice, where he’s been the senior rabbi for the past two years. “It’s really fulfilling to know that I’m coming to work just across the street from the place that meant so much to me when I was an undergrad.”

How does his background in entertainment influence his perspective as a rabbi? His time as a lover of literature has given him “comfort with audacious interpretation,” he said. “You feel a bit more liberated to be creative with the text, but at the same time you have a much deeper, more profound appreciation and love for it.”

Hayon sees parallels between his previous and current work. “Spending time analyzing, parsing, preaching about religious text becomes a devotional activity, just like an actor getting to know his script or a literary critic getting to know the manuscript,” he said. “That becomes a devotional activity that is an expression of your relationship with the divine.”

PORTS OF CALLING

Some people hit a bump in the road on the way to a goal. For Chris Blache ’97, a native of New Orleans, that bump was more of a sandbar, and the road a fabled river. For a time, he was stranded there, between his parents’ dreams for his future and his own longing for open waters.

At Rice, Blache lived in Sid Rich, studied psychology and played club rugby. He loved college life so much that he decided to pursue a graduate degree and become a professor. For a time, he settled in at the University of Northern Iowa to study and teach organizational psychology. “I was doing well; it was OK,” Blache said, “but I didn’t feel challenged in school or life.” What he knew for sure was that he wasn’t happy.

While Blache was in graduate school, his dad, Greg, was coaching the NFL’s Indianapolis Colts. His son would attend home games, driving over from Iowa when he could. It was at a game against the New Orleans Saints that Blache glimpsed a different future for himself. His uncle, C.J. Blache, a prominent attorney and lobbyist in Louisiana, had brought a group of Mississippi River pilots to the game.

The tight-knit and highly skilled pilots operating on the Mississippi River are recruited mostly from families who go back generations in the profession. At the time, only one of the approximately 200 licensed river pilots was African-American, and they were under pressure to diversify their ranks. Blache had visited with the pilots when he was still at Rice, and they knew his uncle well. They wondered if this young Rice grad had any interest in learning their trade. “I saw what my parents wanted me to do but realized I was at a point where I could make my own decisions,” Blache said. After finishing the semester, he drove home and signed on as a cadet officer on a Greek merchant vessel.

For room and board and little else, Blache spent 13 months traveling the world and learning about ships and navigation. Upon returning to New Orleans, he became an apprentice Mississippi River pilot. “I just loved being on the water,” he said.

For room and board and little else, Blache spent 13 months traveling the world and learning about ships and navigation. Upon returning to New Orleans, he became an apprentice Mississippi River pilot. “I just loved being on the water,” he said.

Blache is a “bar pilot,” guiding ships from the Gulf of Mexico to Pilottown, La. Crossing from the Gulf into the river is the trickiest part of a winding 30-mile stretch. “You don’t want to hit another vessel, and you don’t want to get stuck in the mud,” he said. The stakes are high. In terms of tonnage, south Louisiana is the busiest port in the nation. Every kind of ship goes up the Mississippi, from small cargo carriers to Navy vessels and cruise ships. They carry grain, coal, oil, chemicals, finished goods — and people, in the case of cruise ships.

The pilots board in all kinds of weather during their two-week shifts. The boarding routine — jumping from one moving boat to another at speeds of about 10 to 12 mph — requires finesse. “We climb on the top of our [pilot] boat and then time our jump across to the ship’s rope ladder,” said Blache. “Some days, it can get quite hairy.”

After 2012’s Hurricane Isaac, a cruise ship limped into port, its passengers desperate to get home. “A cruise ship has so much freeboard [ship sticking out of the water], it’s like a giant sailboat,” Blache said, remembering the high winds and waves in the Gulf that buffered the ship. Getting on board took an hour. Adrenaline flowing, Blache steered the ship to port.

After Hurricane Katrina, it was the port pilots in Houston who took them in, temporarily providing housing and an administrative home. “They helped us in so many ways. … It’s a very small fraternity. And they’re like family.” — LYNN GOSNELL

FOUND IN SPACE

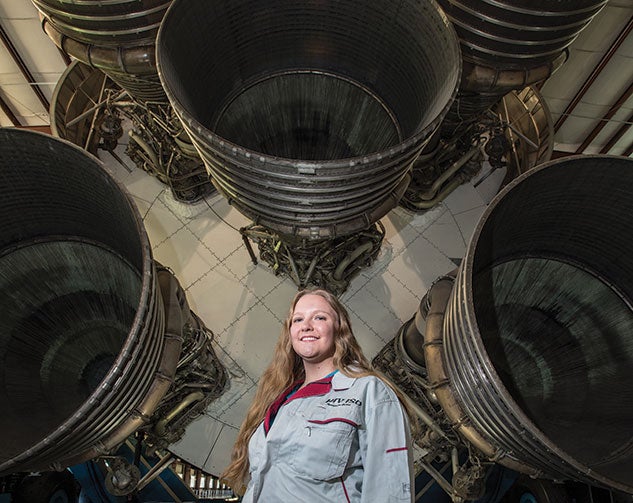

Lifelong Houstonian Amanda Humphrey ’07 spent some years teaching science to high schoolers. Now, the Rice chemistry major helps astronauts track down missing gadgets on a space station.

Humphrey finds chemical reactions fascinating, thanks to an engaging high school science teacher and a father who “used to do little chemistry experiments with me and my brother when we were young.” While teaching wasn’t her ultimate goal, she preferred the classroom to the laboratory. “I had worked in a lab before, and doing the same tests over and over probably wasn’t going to be my cup of tea,” she said. So she taught chemistry — and piloted a forensic science program — at Cypress Falls High School in northwest Houston.

Over the course of seven years, however, she realized that the nature of teaching didn’t suit her. “I wanted to be the person who was doing stuff, rather than teaching people how to do stuff.”

Her first foray into another career was something a little different: applying to become a special agent for the Federal Bureau of Investigation, an idea she’d had for some time. She got to the first phase of testing for the position but then had to quit because of a medical condition.

Her next move was pursuing a master's degree to follow another longtime interest, and Rice was again the place to do it via the professional science master's program in space science. “I’ve always been interested in the space industry and space in general,” she said, recalling trips to NASA’s Space Center Houston as a kid. “I don’t know how people don’t love space.”

Once she was the student and not the teacher, Humphrey enjoyed the all-space schedule and learning from people who had worked in the industry, like astronaut Leroy Chiao, who commanded the International Space Station on his last expedition in 2005. While interning at the Johnson Space Center, she worked on a system that would reclaim water from wastewater brine.

“I don’t know how people don’t love space.”

At last, she has her dream job, working in the human spaceflight program at the Johnson Space Center. Her title is flight controller, specifically an inventory and storage officer. Her team keeps the International Space Station organized throughout continual crew rotations with cargo shipments to and fro and a tendency for objects to float away.

There’s a special urgency to locating objects on a space station. “The problem is that the crew can’t do repair activities or science experiments or any activity if they can’t find the items they need,” Humphrey said. When something gets lost or misplaced, she helps create a “wanted poster” that includes a picture of the object and a list of possible locations.

Her different experiences have intersected in unexpected ways, she said. “I don’t naturally get up in front of people and start talking to them, but in teaching you have to do that every single day. And a lot of that comes into play in being a flight controller. You have to get up and talk to the flight director and say ‘Hey, I need the crew to do this.’”

“The other thing is not to freak out, to keep your game face when things go wrong,” she added. “In high school, you can’t let the students see you crack. And the same thing is true if you hit a bad situation in mission control. You have to keep your cool.”

SUMMIT OF SUCCESS

Ariana Myers ’92 spent more than a decade in finance, living in Europe and working as an investment banker. A period of reckoning and a journey up a mountain brought her from Moscow to Marin in California, where Myers has built a more human-oriented career in home care.

At Rice, Myers initially studied engineering, but then a linguistics class drew her interest. “I found it really fascinating, the cognitive elements of linguistics,” she said. She wound up majoring in linguistics, studying Russian and spending a semester in Moscow.

Although Myers didn’t have a business background — she edited technical manuals in her first job out of college — she ended up in the financial sector at Enron, working from the company’s London office.

After earning an MBA from Columbia in 2002, she returned to London and switched to commercial real estate finance. By 2007, the global financial crisis was looming. Feeling qualms about how her employer was handling the economic climate, she left to work in private equity with a client in Moscow. But she was already starting to feel the pull toward a new direction — something with more than a financial bottom line. “I was moving money in circles, and I couldn’t look at what I was doing and feel that there was real value to it. I also knew I needed to make a break to make a change.”

So in 2010, Myers quit her job and set out on a new, adventurous quest — to summit the world’s highest mountains. She chose Mount Kilimanjaro as her first summit and next climbed Mount Elbrus, the tallest mountain in Russian and in Europe. “The metaphor is obvious,” she said, “aiming for something higher, going where the air is clear.”

Her next challenge was Mount Aconcagua in Argentina. During the climb she struck up a friendship with a fellow climber, Chuck Nuzum, who was from the Bay Area. “Our first date was summiting the tallest mountain in the Western Hemisphere.” Myers soon moved to the Bay Area to join Nuzum, and the two were married in 2012.

In California, the couple started a business helping seniors and people with disabilities keep living in their own homes. A year later, their Right at Home franchise was thriving. It’s work that Myers finds deeply meaningful. “Every day I know I’m helping people — our clients, our caregivers and our office team — and this is the value I was searching for.”

Her newfound success and fulfillment represent a summit moment for her, culminating in the birth of their daughter in 2016. The metaphor has held up as she looks back on the tough moments in climbing. “You think, can’t do it, can’t do it, can’t go any further, and then you just go, you just do it anyway, you take another step,” she said. “You feel like you can’t go on, and then you just keep going, and then you get there, and it’s amazing.”

REINVENTING LIFE

To be a good police officer,you have to be very aware of details, like the color of a bruise. You have to be highly attuned, intuitively, to body language, to everything from how they use their eyes to the dirt under their fingernails. Each and every detail could help you solve a crime or save your life.” That’s how you describe working in law enforcement when you’re also a poet.

Sarah Cortez’s circuitous career path began in the realm of the humanities, with a double major in psychology and religion at Rice in 1972, followed by a master’s in classical studies at the University of Houston, which let her ponder ancient beginnings and study old languages. With that background, she began teaching high school Latin.

But Cortez found it difficult to support herself in that job and decided to switch to a business career. She earned a master’s in accounting and worked in corporate finance for more than a decade. At the same time, she diligently nurtured her love of language. “All those experiences and knowledge from my psychology degree and my classics degree were going right along with me. It was in my heart, my mind,” she said.

“All those experiences and knowledge from my psychology degree and my classics degree were going right along with me. It was in my heart, my mind,” she said.

In her spare time, she volunteered for a civic group trying to fight crime in Houston’s Montrose neighborhood. As a leader in the Neartown Association in the 1980s, she got to know and respect a number of police officers. “I started meeting more police officers and doing ride-alongs,” she said. “And I just fell in love with the idea of becoming a police officer.” So she quit her corporate job and became one.

Police work coincided with a blooming literary career. Her years as a police officer fueled writerly contemplations about the messiness of life. “There’s a lot of sadness, and there’s a lot of dirt [in police life],” Cortez said. “I mean physical dirt. People with lice, people with tuberculosis, people who may only bathe once a month. People who may be physically clean, but man their lives are a mess. ... There’s just a lot of things that for whatever reason have spun out of control in somebody’s universe, and that tends to be when police officers are called.”

Her writing drew accolades, and in 2000 she accepted a position as a visiting scholar in the University of Houston’s Center for Mexican American Studies, teaching creative writing. She now works as a memoirist, fiction writer, poet and editor as well as a teacher, offering intensive writing classes out of her home. She remains a reserve police officer.

Cortez describes her path of constant reinvention as a long process of gaining self-knowledge. “I had to know myself extremely well to be able to know that I could be a police officer, that I could save a life and lose my own, or that I could take a life and save someone else,” she said. For Cortez, the hard work of knowing oneself “takes your whole lifetime.”