Syllabus: Monster Mashup

It’s the Jekyll and Hyde of the Rice course catalog: one class that embodies two seemingly opposite characters. Monster, co-taught by professors Deborah Harter and Michael Gustin, combines biosciences and the humanities in the first Rice course ever cross-listed in both disciplines.

BIOC/HUMA 368

BIOC/HUMA 368

Monster: Conceiving and Misconceiving the Monstrous in Fiction and Art, in Medicine and the Biosciences

(Spring 2016)

DEPARTMENT

BioSciences and Humanities

DESCRIPTION

Monsters are products not just of nature but also of human conception. They wander forth out of evolution, out of language, out of brain physiology and social disjunction. It is this variety of the monstrous — and its traces in the domains of art and bioscience, fiction and medicine — that we endeavor to capture this semester.

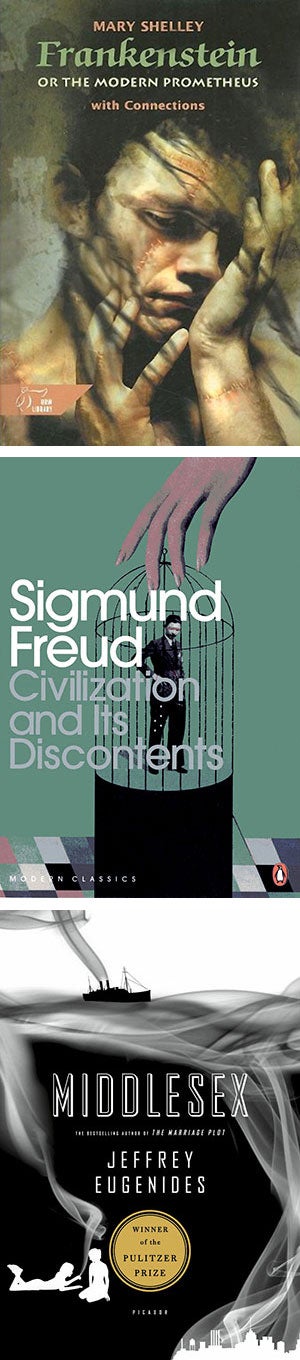

It’s the Jekyll and Hyde of the Rice course catalog: one class that embodies two seemingly opposite characters. Monster, co-taught by professors Deborah Harter and Michael Gustin, combines biosciences and the humanities in the first Rice course ever cross-listed in both disciplines. The professors alternate lesson plans on cultural archetypes of monstrosity, touching on topics like genetic mutations, disorders of the brain and body, disability and artificial intelligence. Gustin teaches the science (for example, the neuroanatomy of psychopaths) while Harter teaches corresponding fiction and films (for psychopathy, “The Silence of the Lambs”).

COURSE HIGHLIGHTS

Most provocative insight

In one lecture, Gustin told students they all had “a little psychopath inside,” according to Selina Chen, a sophomore studying math and science. “He said we may need a little of that to survive and compete,” she explained. That point, coupled with a close reading of Jekyll and Hyde, inspired one of Chen’s essays:

“Dr. Jekyll can’t accept that Mr. Hyde is a part of himself. I compared that to the inner conflict we all face, and how, whenever there’s something I’ve done that I’m not proud of, I try to externalize it.”

Toughest challenge

Teaching such a diverse group of students has posed a challenge for the professors. They’ve had to adjust to each other as well, and often butt heads, albeit respectfully. “We’ve both evolved as teachers,” Gustin said. “I’ve had to become familiar with a literature that I was aware of but maybe not well versed in.”

“In my mind,” Harter said, “our students couldn’t possibly understand interdisciplinarity better than they do as they watch the two of us both support and question each other in regular battles of warm intellectual exchange.”

Most monstrous monsters

After studying the social response to lepers, Giancarlo Latta was struck by the way people tended to conflate physical illness with moral contamination, jumbling their fear of leprosy with a fear of the people afflicted by it. Latta, a junior majoring in violin performance, noted a parallel with the way gay men were treated in the early days of the AIDS epidemic. Discussing Latta’s paper, Gustin said that history reveals a universal impulse to identify people who are different and to “out” them, segregating them from the mainstream. The stigmatized groups have varied through the ages, but the outing has remained a constant — and its effects have proved more dangerous than any epidemic.

Biggest takeaway

While the class offers an introduction to some of nature’s strangest aberrations — the genetic mutation, for example, that turns the ordinary whippet into a hypermuscular monster dog — it’s less a lineup of hideous creatures than an examination of the way people from different cultures and historical eras have labeled others as fearful and sought to marginalize them. As Harter explained, it’s a way to learn more about who we are by what we’re afraid of.

— Jennifer Latson

This story was published in the Spring 2016 issue of Rice Magazine