Walkabout

Dive into the lifelong journey of discovery of Shepherd School alumna Gabriela Lena Frank.

Winter 2024 | By Steven Boyd Saum

On a stunning September day in the hills of California’s Mendocino County, just above Anderson Valley and the little town of Boonville, where the redwoods meet the vineyards, composer and pianist Gabriela Lena Frank ’94, ’96 pauses to reflect on where recent months have taken her. She is at home with her husband, cat and three dogs, sitting on their terraced deck within sight of the school where she nurtures a music program. The past year has brought Frank an arrival: the premiere of her first opera, “El último sueño de Frida y Diego” (“The Last Dream of Frida and Diego”), building on three decades of work as a composer.

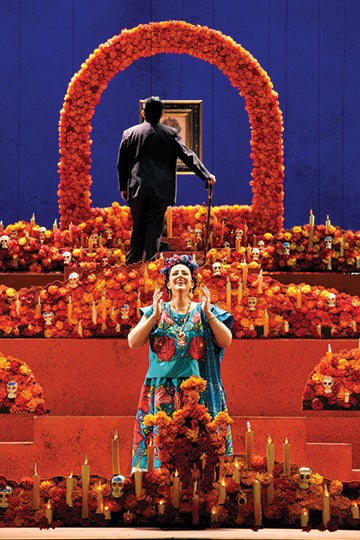

Sung in Spanish, “Frida y Diego” is the tale of a journey between the land of the living and the dead. Frank co-wrote the opera with Pulitzer-winning playwright Nilo Cruz, a frequent collaborator over the past decade and a half. For this epic project, they set out to tell the story of the titular Mexican artists, Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera — not to craft an operatic biopic, but as a folkloric tale where Kahlo is called to escort the dying Rivera to the underworld where she already resides, Orpheus in reverse.

“Frida y Diego” premiered with the San Diego Opera in fall 2022. The San Francisco Opera staged it as part of its centennial season in summer 2023. The Los Angeles Opera would stage it that fall.

It has brought a new scale of media attention — although Frank, the recipient of a Latin Grammy and a Guggenheim Fellowship, is no stranger to accolades. Her work as a composer-in-residence with numerous institutions has taken her from Houston to Philadelphia, Detroit to Seattle. In 2017, the Washington Post included her in a list of the most significant women composers in history.

Sometimes she will tell audiences that when they hear that word — “composer” — she knows she’s not who they picture: a disabled, middle-aged, multiracial woman. She has dark, curly hair and has worn hearing aids since she was a child — a necessity for the high moderate/near-profound hearing loss she was born with.

As for how she’s found herself at this point in her journey, here’s part of the answer: “If I look at the projects that I have now — 30 years later — for many of them, you could trace a lineage back to Rice.” Her work as a composer is deeply reliant on personal relationships. “I don’t even mean powerful people, just colleagues. I talk with somebody from my school days at Rice every week.”

Finding joy in music

Frank’s mother was born in Peru, of mixed Indigenous and Chinese descent, and worked for years as a glass artist. Her father is Lithuanian Jewish and had a career as a Mark Twain scholar at the University of California, Berkeley. The couple met when he served as a Peace Corps volunteer in Peru. Gabriela was born in 1972, their second child. While she was still a toddler, her parents noticed that she spoke differently from other children, though they weren’t sure why. They did recognize, however, that she had a gift for music. The family acquired a castoff spinet piano, and Frank recalls sitting with her grandmother as she played and sang Depression-era tunes.

“Then I would just add some notes,” Frank says. “There was this special bond we had. There’s a musical gene in the Frank family on the Jewish side, like a physical trait you could trace through the family.” That trait skipped her father and brother. “Then I came along. ‘She has it!’ they said. I loved the piano, because I could hear it just enough, and I could feel it.”

It was Frank’s kindergarten teacher who identified signs of hearing loss; the teacher had previously worked with children in the Deaf community. Frank was fitted for hearing aids. She also began piano lessons with Babette Salamon, a refugee from South Africa who had studied at the Royal College in London. Salamon taught her traditional classical music with the patience necessary to work with a pupil with perfect pitch; Frank could hear something once and play it, lessening her motivation to learn to read music.

I loved the piano, because I could hear it just enough, and I could feel it.

As a high school student, Frank was transfixed by the geopolitical story unfolding behind the Iron Curtain — glasnost, perestroika, the fall of the Berlin Wall — as well as the democratic uprising crushed at Tiananmen Square. “What a time to have your adolescent political awakening,” she says. A future in Slavic studies might have been in the cards, were it not for a summer composition program at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music. She put her first piece on paper and heard it played by her peers. “I was hooked, instantly.”

Scholarship support from Rice brought her to the Shepherd School of Music. “It was just so brilliant and vibrant. This whole world of classical music exploded to me.” Frank studied composition with the school’s founding dean, Sam Jones. New faculty and studios arrived, feeding a joy of new music in young composers and performers. Frank wanted to write music more complex than she could improvise, so she buckled down and began to truly read music. She also came to recognize the value of understanding music from a performer’s perspective.

“I took piano lessons as if I were a piano major,” she says. She played for the percussion ensemble under Richard Brown, accompanied performers in the vocal studios and performed chamber music. In fact, she says, “I learned more from composing because I was at a performance school than I did from the composition department.”

Jeanne Kierman Fischer, a member of the piano faculty, introduced Frank to the music of Alberto Ginastera — the first Latin American composer Frank had encountered. “His work blew my mind, because the music seemed so familiar to me.” Traditional Latin American music was part of Frank’s upbringing, as was the folk scene in Berkeley. “Here’s this guy with a different life story, putting it into classical music. I credit Jeanne for giving me kind of the right cultural witness at the time I needed it. I started seeing music as more than just acrobatics or something that’s fun to do or as kind of a vague mission of upholding the past. Now, it seemed something very specific to me.”

After completing her bachelor’s and master’s degrees at Rice, Frank enrolled in a doctoral program at the University of Michigan. She studied with William Bolcom, known for incorporating popular culture into his music. “Why aren’t you in Latin America?” she recalls him asking. “You have a lot to say, but you need to find it, and to find it you need to travel.” She began a series of mostly self-funded trips to Latin America with her mother. “I had the most intimate kind of guide that you could have. The person who gave me Peru was the one showing it to me.”

At first, Frank thought she needed to be deliberate about hearing a lot of music. But as she spent time there, she realized how important it was to absorb the culture and see the people all around her. “Things that are ordinary for them are pretty miraculous for me. My music changed a lot as a result. I became more like a storyteller.”

I started seeing music as more than just acrobatics or something that’s fun to do or as kind of a vague mission of upholding the past. Now, it seemed something very specific to me.

Over tea, she talked with an instrument maker, Señor Huamanga, who told the history of each instrument, which he tailored to his clients’ needs. “He felt it was so important to make beautiful instruments that could last, to keep telling the story of Peru.” She met Familia Pillco, three generations of musicians who play traditional Inca tunes, bending the vibrato on their violins the way that quena players do on traditional Andean flutes. “Because the violin can do other things that quenas can’t, they add in other things. This is the role of culture: We take it, we eat everything, and then we make new food and new recipes.”

In this case, Frank isn’t just speaking in metaphor: The grandfather insisted they hop in his truck and head to the spot in Cusco with the best “picarones” — doughnutlike creations drenched in syrup. “When I went back to composing my music, the delivery went past the page,” Frank says. “I had to think about bringing senses like that to life, connecting to my musicians as if we were eating picarones across the music stands. But I didn’t want to do a literal translation. What helps me is to remember that I have a violin, and I have quena flute, and just go fanciful. What if they had a baby? What kind of music would it make? That’s your job as an artist: You’re kind of a journalist, kind of an ethnomusicologist. But you’re trying to use your imagination to push it forward. It’s really ingenious when you do it in a way that’s revelatory but authentic, too.”

A gatherer of stories

Aspiring to tell stories of human movement, culture and development, Frank wrote “Sonata Andina” (“Andean Sonata”), for piano, dedicated to her maternal grandmother, Griselda Cam. It weds traditional piano with sounds inspired by Andean folk instruments — drums, flutes, panpipes, guitars and marimba.

“It draws inspiration from the idea of mestizaje, as envisioned by the Peruvian writer José María Arguedas,” Frank writes in the program notes, “whereby cultures can coexist without the subjugation of one by the other.”

Over the past quarter century, Frank has completed more than 100 works for orchestra, string quartet, voice, solo instruments and more. Her “Walkabout: Concerto for Orchestra” was completed in 2016 and draws on her travels with her mother in Peru. The concerto was commissioned by the Detroit Symphony Orchestra and premiered by assistant conductor Michelle Merrill.

While serving a residency with the Houston Symphony under Andrés Orozco-Estrada, she composed the epic “Conquest Requiem,” a work for orchestra and chorus sung in Spanish, Latin and Nahuatl, the language of the Aztecs. Call it a reclaiming of history on behalf of a woman who left no historical record in her own words: “Malinche, who was Cortés’ — they call her ‘concubine’ — really, captive,” Frank says.

“Cortés seized her, they had a child, Martin Cortés — one of the first mestizos.” Frank wove in elements of the Latin Mass for the Dead along with new text written by Nilo Cruz; she worked with an expert on Mesoamerican languages for the sections in Nahuatl.

Beyond the concert hall

Despite her historically inspired works, Frank says, “I’m a living person. And I don’t want to do a literal translation of a native culture that people will keep in the museum. Where do mixed-race cultures come in? Where does modernity, as well as tradition, come in?”

In 2017, Frank and her husband, Jeremy Lyon, founded the Gabriela Lena Frank Creative Academy of Music. Its goal: to support a talented and diverse crew of emerging to composers, bringing them to Boonville for residencies, forming yearslong relationships, and “creating an experience that would give them a strong professional/artistic boost; and to encourage composers to think of the arts as indispensable to communities beyond the concert hall.” Dozens of composers have already benefited from the academy. It’s Frank’s way of enlisting others on the journey and helping them steer their own self-determined artistic lives.

I don’t want to do a literal translation of a native culture that people will keep in the museum. Where do mixed-race cultures come in? Where does modernity, as well as tradition, come in?

Boonville lies two hours north of the San Francisco Bay Area. “It’s one of these rural areas where you don’t have to go very far to be connected to big city life and art,” Frank says. “I also feel that, as an arts citizen, I’m needed more here. My composers see that.”

Comprising a population of around 1,000 are longtime rural families, vestiges of the hippie generation, newcomers — perhaps with a second home — and the Central American community, many of them vineyard workers. Within walking distance of Frank’s home is Anderson Valley Junior-Senior High School, where Frank and the academy have forged a teaching program. The students have taught Frank lessons as well — including how quickly they could take to the arts.

A few years ago, the Chiara String Quartet and the Del Sol String Quartet, which both included graduates of Rice’s Shepherd School of Music, were visiting the academy; Frank had them play for the kids. She had students — mostly boys, mostly Latino — write music with help of computer software. “Now, these 16- to 17-year-old boys are really hard to reach — too cool for school. They’ve only heard their little bit of music played back on the computer. One kid is like this” — she crosses her arms, tilts her head back. “You know, real skeptical. The quartet plays it. Of course, it sounds amazing. I see the kid nod with approval but try not to show it. I say, ‘OK? You want it louder or softer?’ ‘Louder.’ So, they play it really big. ‘And now?’ ‘Faster,’ he says, ‘really fast.’”

Then, Frank told him, “‘I’m going to have them do it pizzicato, check this out.’” That was a breakthrough moment. “Some of the boys went, ‘That was tight!’” Chins up, fist bumps all around.

“We did a concert in the cafeteria: 17 world premieres. They wrote program notes. Parents came — it was the most blended audience I’ve ever seen. People were weeping — because their kids were poets.”

Arts and service

Not coincidentally, Frank’s vision for American classical music starts with education. “First, I would enrich all the public schools with thriving arts programs.” The focus would be on schools in underrepresented communities, and she would not solely emphasize performance; rather, she would advocate for children writing their own stories and music and others performing it.

It’s also important to destigmatize community work, Frank says, so artists don’t worry that they will not be taken seriously if they want to teach in local public schools. “Part of the power of my academy has been that my composers come and have the life that they want. They see me live quietly, how much energy I put into this little school,” she says. “I think about what they need, as a matchmaker for great performers. And I say, ‘Now you guys go out, because you’re supposed to go farther than me. Not just because you’re younger, you’re next, but there’s only one of me. We can’t do this alone.’”

Looking ahead through spring 2024, there are scores of performances of her compositions by orchestras and opera companies from Austin to Edinburgh, Montreal to San Jose. In March, the Shepherd School Chamber Orchestra will perform “Elegía Andina” at Rice. Recordings are in the works, including the concerto “Walkabout” by the Nashville Symphony, a Grammy-winning orchestra, for the Naxos label.

“Creatively, I’ve got some wonderful projects coming up,” Frank says. “I have my swan song at Philadelphia Orchestra,” where she has been composer-in-residence. “It’s a big 45-minute orchestral work that we’re thinking of like a Latin American ‘Rite of Spring.’”

Frank and longtime collaborator Cruz have a significant list of projects they would like to undertake. “Anna in the Tropics,” the play for which Cruz won the Pulitzer, is a natural candidate. For the Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra, Frank is working with writer Drew Lanham — a Black American ornithologist, poet and 2022 recipient of a MacArthur “genius grant” — writing orchestral songs based on Lanham’s essay, “What Do We Do About John James Audubon?” She is also undertaking some chamber works with friends.

“I’m now in my 50s. I want to slow down,” Frank says, “tell big stories, but just a few of them — you know, fragment less.”