The Deadball Files: Author Q&A

A mystery series takes a swing at baseball scandals, real and imagined.

Fall 2024

Interview by Jennifer Latson

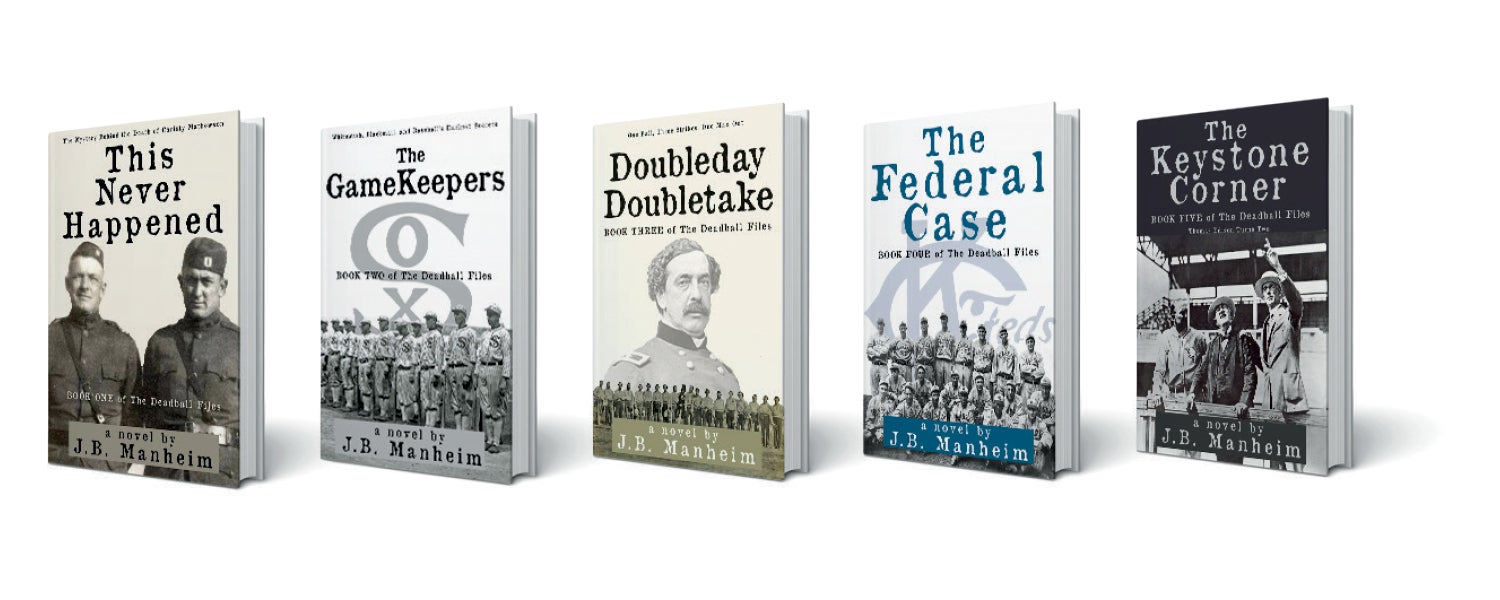

The so-called deadball era in baseball, from 1900 to 1920, marked a turning point for the game as it evolved from low-scoring contests with few home runs to the livelier, higher-scoring games of modern baseball. In “The Deadball Files,” a series of novels by Jerry “J.B.” Manheim ’68, the era is a backdrop to fictional mysteries interwoven with real historical moments. Manheim, a professor emeritus at George Washington University, where he taught political communication and spent much of his career studying propaganda and cover-ups, uses those themes as the plots of his novels. We spoke to Manheim about the series and his inspiration.

What inspired you to write this series?

In 2018, I was watching “Antiques Roadshow,” and there was a military history collector in Georgia who had picked up a box of papers from a World War I training camp near Augusta: Camp Hancock. He had found a daybook for a training unit there that had seven or eight future Hall of Fame baseball players — including Christy Mathewson and Ty Cobb. According to historical accounts, that duo had joined the newly formed chemical warfare service at the end of the 1918 season and shipped over to France, where there was a training accident. Mathewson was exposed to poison gas and died a few years later as an indirect result.

The 'deadball era' was a hotbed of firsts: the first manned flight, the first world war, the emergence of the modern presidency, the first pandemic of the modern era. But in baseball, there was a lot going on, too.

But none of the baseball histories or player biographies made any reference to what was obviously a propaganda unit — formed to encourage more men to enlist — months earlier. The interesting thing is that this daybook showed that, while they were at Camp Hancock, Mathewson and others spent considerable time in the base hospital. There were a lot of strange activities going on in the training unit, and then it disappeared: a propaganda unit that generated no propaganda. So that got me thinking about what else might have happened, and what the military might have wanted to cover up, which formed the premise for the first book in the series, “This Never Happened.”

What drew you to the deadball era in particular?

The era was a hotbed of firsts: the first manned flight, the first world war, the emergence of the modern presidency, the first pandemic of the modern era. But in baseball, there was a lot going on, too. In 1903, the National Baseball Commission was established to govern the major leagues. You had the start of the World Series, the redesign of the baseballs used in the sport, and litigation that led to the antitrust exemption for baseball that forms the core of their business model. You had larger-than-life personalities in players like Mathewson and Cobb, and at the end of the era, Babe Ruth. So, you have these concurrent dynamic periods interacting with each other.

How does your scholarly work in political communication inform these novels?

My research focused on the communication strategies and tactics that governments, companies, policy advocates, political movements, insurgent groups and others use to achieve their goals. That led me into studying persuasion and propaganda, cover-ups, that sort of thing. If there’s political messaging that looks like it might have been artificially created, I’m always interested in how that happened. That’s an underlying theme in the books, too.

The books end up with some true, researched, annotated baseball history and general history, but I don’t feel bound by the facts. I like to play with the line between what’s real and what’s not, and the question of how we know what we know — whether what we think we know about history is really true.

You mentioned that you don’t like the label “historical fiction” for this series. Why not?

I think of the books as multiperiod fiction. Every book is grounded in baseball history and more general American history, but the main part of every plot takes place in the present day. They’re multilinear, and the lines tend to converge toward the conclusion of the book, so that something that happened 100 years ago somehow explains something that happened in the present era, and maybe a contemporary event answers a question about something that happened in another era. So, it’s a little limiting to call it historical fiction.

What’s next?

I just sent off the sixth and, I think, last book in the series. It’s called “Field of Schemes.” The villain in this series emerges in the second book: the commissioner of baseball, a former professional poker player who ran for Congress and then used his Senate standing to blackmail his way into controlling the game of baseball. In the sixth book, there’s a lot more background on him, and a lot of the story revolves around Congress. I used historical parallels between things going on in Congress in 1909 surrounding the very first congressional baseball game, as well as the commissioner’s experience rising to power in Congress, with a contemporary theme that has to do with the reintroduction of professional gambling in baseball today — and I have a twist on that.