Paging Through History

“Doc Talks,” a series of live webinars and companion podcasts, invites audiences to listen in on conversations about Rice’s history that are reshaping how we think about our past, connect to the present and plan for the university’s future.

By Lynn Gosnell

An astonishing variety of documents — handwritten mortgage deeds and business records from the 19th century, formal correspondence and scribbled notes, Rice Thresher articles and photographs from the “Campanile,” and campus blueprints and maps — fueled the conversations hosted weekly by Rice historians Alexander X. Byrd ’90 and Caleb McDaniel during the 2020–2021 academic year. Each of these documents, which also included clips from homemade videos, musical recordings and professional documentaries, reveals new information about Rice’s history, and more often than not, they raised new questions for Byrd and McDaniel to ponder.

As part of their work as co-chairs of the Task Force on Slavery, Segregation and Racial Injustice, the historians met each Friday at noon via Zoom for the talks, bringing the real-time detective work of primary research into view, as well as answering the audience’s questions. In addition to bringing their own decades of distinguished scholarship to bear on this research — Byrd, an associate professor of history whose expertise is in Black life in the Atlantic world and the Jim Crow South, and McDaniel, a professor of history who studies slavery, antislavery, emancipation and the Civil War era — the two are engaging hosts. The punny name of the series refers both to the professors and the objects at hand.

Each webinar typically opens with a friendly greeting: “Good afternoon, Dr. Byrd,” says McDaniel, with a smile, broadcasting from his office in the Humanities Building. “Hello, Dr. McDaniel,” responds Byrd, “It’s Friday” — a statement that often leads into some empathetic reflection on the previous week during an academic year defined by crisis and tragedy. Zooming in from home, Byrd appears framed by a wall of book-lined shelves. Soon, one of the two asks, “Do you have a document to share today?” The documents, shown on screen, typically span centuries, reflecting the expertise of the hosts or that week’s special guests, which include students, alumni or Rice faculty who are part of the multilayered task force research project. What follows is a virtual tutorial into an unfolding search for answers.

For the audience, following along is a lot like being in a small seminar with the coolest college professors. Yet despite the congenial banter of the hosts, the content under discussion could not be more serious nor more consequential. “The research that the task force has been charged with doing is to investigate the ways that Rice University’s history is entangled with and implicated in the history of slavery, segregation and racial injustice,” says McDaniel.

Rice students and recent graduates are integral to the “Doc Talks” investigations — their research is featured in three different webinars. The project also highlights the Racial Geography Project, a research collective of students and faculty that maps histories of racism on campus. Faculty guests share their expertise, and in one episode, the staff of the award-winning Woodson Research Center give an informative tour of the archives.

This fall, the “Doc Talks” live webinars are back every Friday at noon via Zoom. The “Doc Talks” podcasts, produced by Kate Coley ’11 and student media fellows, are also returning. Here are a few examples of the documents fueling these vital conversations.

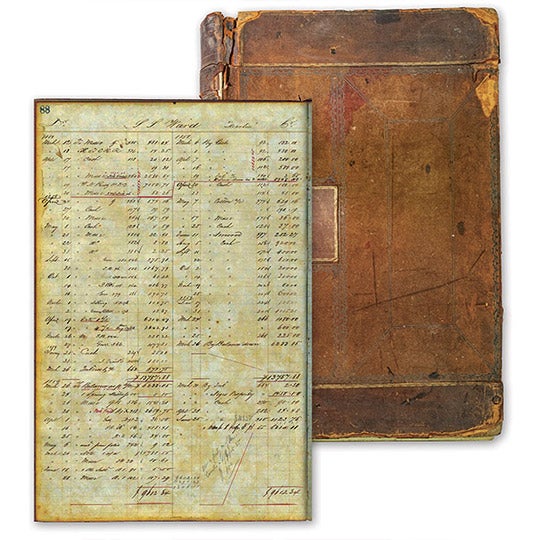

1. Business Ledger, 1858–1859

On Sept. 18, 2020, McDaniel and Byrd welcomed four current and former student researchers — Edna Otuomagie ’17, Andrew Maust ’18, Indya Porter ’22 and George Huang ’22 — to “Doc Talks.” The document pictured here — one page of a 787-page leather-bound business ledger belonging to William Marsh Rice — was shared by Maust. Inspired by a class with McDaniel, Maust started digging into the Woodson archives to learn more about William Marsh Rice’s connections to slavery before, during and after the Civil War.

On Page 88, in meticulously recorded debits and credits with one business associate, Maust saw an entry for “Negro property” in the amount of $1,450. “To actually see this transaction listed, that’s what drew me to this document,” he says. To further contextualize the entry, Maust shared some additional research he had published in the Rice Historical Review. At this time, Texas lacked a cohesive banking system, and wealthy merchants like Rice often functioned as bankers who supplied cash and collected debt — in this economy, enslaved people were property, eligible for debt collection. The document raises more questions than it answers, the historians note. Little is known about the nature of this particular debt or the identities and fates of the person or persons listed here.

2. An Iconic Photo, 1965

The first episode of “Doc Talks,” held Sept. 11, 2020, established the project’s scope and expertise by highlighting documents from both the lifetime of William Marsh Rice and the life of the university with respect to the history of Black life on campus. To begin, Byrd turns a critical eye toward an “iconic photo” of Jacqueline McCauley ’70 (1947–2020), the first Black National Merit Scholar in Texas and one of the first two Black undergraduates admitted to Rice. The photo, illustrating a 1965 Houston Chronicle feature, shows McCauley outside Fondren Library, alone, with an expansive view of the Academic Quad in a blue-sky distance. “This photograph sets her at a key point in her life and alludes to the place of the university, the opening up … of that life straight out through the Academic Quad, through the Sallyport and into Houston,” says Byrd. Other photos in the story depict family and social life — a “Black world that helps produce McCauley and sends her to Rice,” notes Byrd. The fact that McCauley went to Kashmere High School in Houston raises questions for the historians. “If I’m at a school and know that six or seven students are going to be at Rice, what does that mean for the relationship between Rice and my school?” Byrd wonders aloud. About Kashmere and other Black high schools in Texas whose students were so long denied the kinds of opportunities available at Rice, he asks, “Is the constant drawing of students from a school a kind of investment and development that matters?”

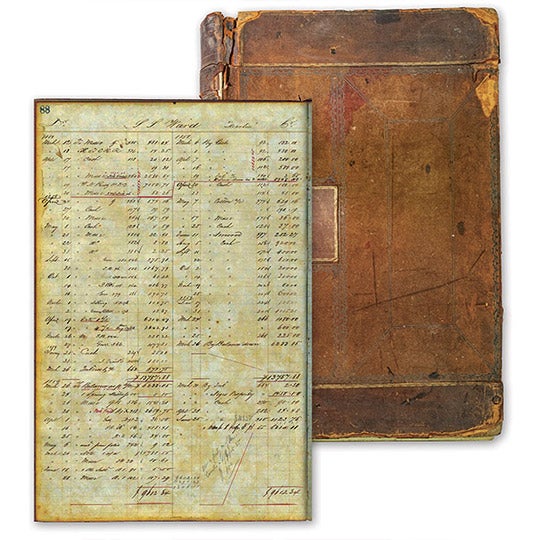

3. Financing a Sugar House, 1849

Also in the inaugural “Doc Talks” webinar, McDaniel highlights a legal document from the 1840s that sheds light on some of the entanglements of William Marsh Rice with enslavement from his earliest days in Houston. The neatly handwritten deed from the Brazoria County deed records details a loan from Rice and business partner Charles W. Adams to James Love for the purpose of building a sugar house. Starting a sugar plantation in 1840s Brazoria County required a lot of upfront capital, McDaniel notes, and Rice, as a wealthy merchant, was in a position to make such loans. What this document reveals is that enslaved people were used as collateral that secured the loan for the sugar house. “The collateral makes all of this possible,” Byrd says. In the document, all the enslaved people living on Love’s Brazoria plantation — men, women and children — were named in the deed. What happened to Harry, Bancola, Bob, Ada, Ellick, George and all the others? “We know that in the 1850s, James Love failed to pay his debt,” McDaniel says, triggering lawsuits, but more research is needed to know how or if William Marsh Rice ultimately got paid and whether enslaved people became a part of this settlement.

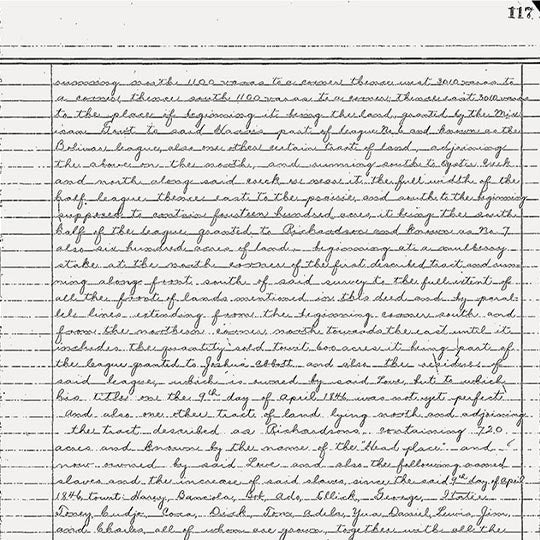

4. Dear President Pitzer, 1965

Rice University’s long and convoluted legal road to desegregation is addressed in a panel discussion produced by the task force; a special conversation recorded with Raymond L. Johnson ’69, the first Black graduate student to enroll at Rice; and via “Doc Talks.” On Sept. 25, 2020, Byrd shared a type-written letter addressed to President Kenneth Pitzer from Johnson, whose graduate studies had been interrupted for a year by a lawsuit from alumni challenging Rice’s desegregation. In this remarkable letter, which was jointly authored by Johnson’s late wife, Claudette Willa Smith, Johnson raises questions about the conflicting messaging he received from administrators concerning policies and publicity surrounding “all matters concerning integration.” After listing many activities that Rice students were asked not to engage in while the alumni lawsuit was litigated, he asks, “Is caution still required in the interest of the suit?”

In the same letter, Johnson advocates for the coming enrollment of Black students. “There is a need for information about the tuition scholarships that will be available.” For Byrd and McDaniel, this letter raises questions about the difference between removing barriers and creating a welcoming climate, of the difference between “desegregation and integration,” for example. “Does Dr. Johnson’s letter represent a community sentiment?” asks Byrd.McDaniel wonders what extra responsibilities Johnson, as a graduate student, carries with him — a concern that resonates 55 years later.

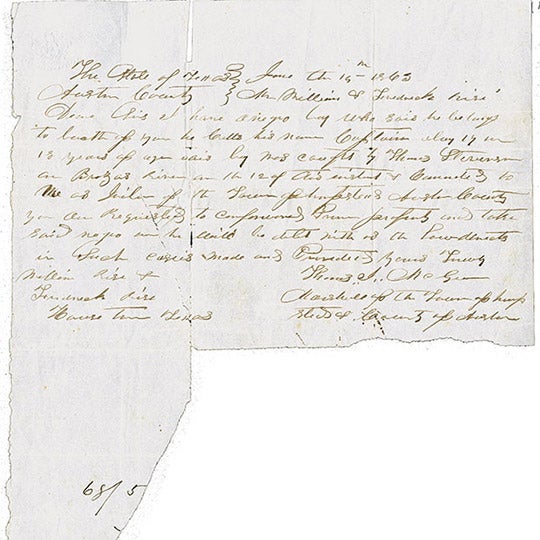

5. A Thwarted Escape, 1863

The document shared Feb. 12, 2021, is a handwritten note dated June 15, 1863, addressed to “Mr. William and Frederick Rice” from a jailer in Hempstead, Texas. (Frederick A. Rice was the brother and business partner of William Marsh Rice.) The note details in brief the capture of a 17- or 18-year-old “Negro boy” named Captain, “who says he belongs to both of you.” The note requests the brothers to “come forward, prove property” and take possession or he “would be dealt with as the law directs in such cases.” Some of the questions the historians had about Captain was how he came to be on the Brazos River and how he understands the ways in which he is possessed by two people. This record is particularly poignant and notable because it occurred after Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation. What did Captain know about the war? How did he escape? There is no record — yet — of whether or not the Rice brothers traveled to the jail to “claim” Captain. This document is from a rare collection housed in the Harris County Heritage Society at Sam Houston Park and is currently being digitized by the Woodson staff.

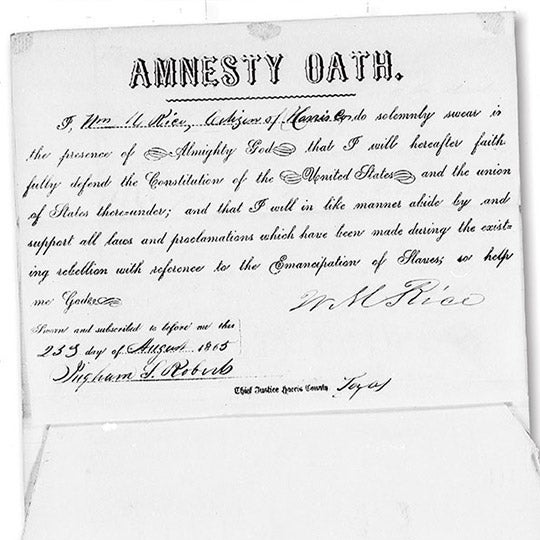

6. An Oath of Amnesty, 1865

A topic that comes up in several episodes of “Doc Talks” concerns the loyalties of William Marsh Rice in the run-up to and during the Civil War years. After all, historian Andrew Forest Muir ’38 wrote in the “Handbook of Texas History” that Rice was a Unionist. On Sept. 25, 2020, McDaniel and Byrd considered this question from the perspective of a remarkable and previously unknown document — the signed Amnesty Oath of William Marsh Rice, stating Rice’s intention to “faithfully defend the Constitution of the United States.”

Attached is a handwritten letter from Rice to President Andrew Johnson. The president had extended a general amnesty to many people associated with the rebellion — with exceptions, McDaniel notes. One of those exceptions was for men in the Secessionist states who owned taxable property in excess of $20,000. In the letter, Rice explains that, before the war, he had acquired “considerable property consisting of real estate, merchandise, bills received, lands, slaves, in an amount far exceeding $20,000.” This document is significant, McDaniel states, because of Rice’s commenting on his views of slavery. Byrd wonders if Rice’s letter follows a kind of template for pardon application, especially among the wealthy. The historians draw out more complexities — layering more economic, political and moral contexts into the conversation.

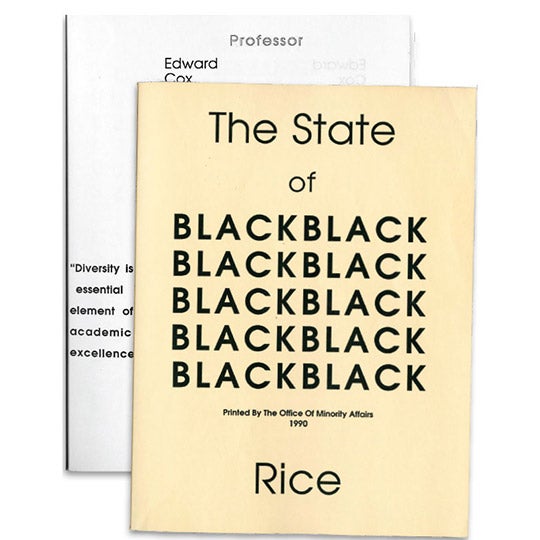

7. From Desegregation to Full Integration, 1990

Sometimes the documents explored by Byrd and McDaniel are more recent in origin — they may even be produced on a computer. Such documents carry familiar names and show with clarity the decades-long persistence of efforts to improve the Black experience at Rice University. “The State of Black Rice” is a collection of essays by faculty, staff and students published by the Office of Minority Affairs in 1990. Byrd focuses on one essay in particular by Edward Cox, now an associate professor emeritus of history. “Professor Cox raises larger questions about what a task force like ours should be about,” Byrd notes. In the essay, Cox asks a series of simple, direct questions: “What are the numbers of African American students at Rice? What percentage of African American students are athletes? How many African Americans are in the tenure-eligible ranks of faculty? Where are the African American administrators? How does the percentage of African American support staff compare with the percentage in the professional staff category?” Both Byrd and McDaniel note that some of these questions fall under the current purview of the task force. And indeed, Cox lights the way: “There needs to be an examination of what has been done since 1965 to promote desegregation and integration at Rice. … A useful mechanism for conducting this self-analysis might be the appointment of a broad-based presidential commission whose task it will be to conduct this study and make recommendations for action.” Thirty years later, Cox serves on the Steering Committee of today’s Task Force on Slavery, Segregation and Racial Injustice.

Would You Like To Be a Citizen Historian?

Readers who are interested in transcribing digitized historical documents like the ones cited here are needed. Go to FromThePage at the Woodson Research Center to learn more.

Citations

- Rice, William Marsh, 1816–1900. “William Marsh Rice Ledger — Old Business.” (1859) Rice University

- Houston Chronicle Sunday Magazine, Sept. 12, 1965, Pages 4–7.

- Rice, William Marsh, 1816–1900. Mortgage Deed, 1849, Brazoria County Deed Records.

- Rice University President’s Office Records: Kenneth Pitzer, UA 083, Box 9, Folder 6, Woodson Research Center, Fondren Library, Rice University.

- State of Texas document to Mr. William and Frederick Rice regarding “a Negro boy who says he belongs to both of you.” June 3, 1863. Rice family papers, Box 1, Folder 4, Heritage Society, Houston, Texas.

- William Marsh Rice Application for Special Pardon, Aug. 29, 1865, Case Files of Applications from Former Confederates for Presidential Pardons, RG 94: Records of the Adjutant General’s Office, 1762–1984, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C., also available on fold3.com.

- Byrd, Alexander X. “The State of Black Rice.” (1990) Chandler Davidson Academic Papers, UA 189, Rice University.