We Don’t Know: How to Break Down “Forever Chemicals”

Chemical engineer Michael S. Wong searches for ways to remove PFAS pollutants from water.

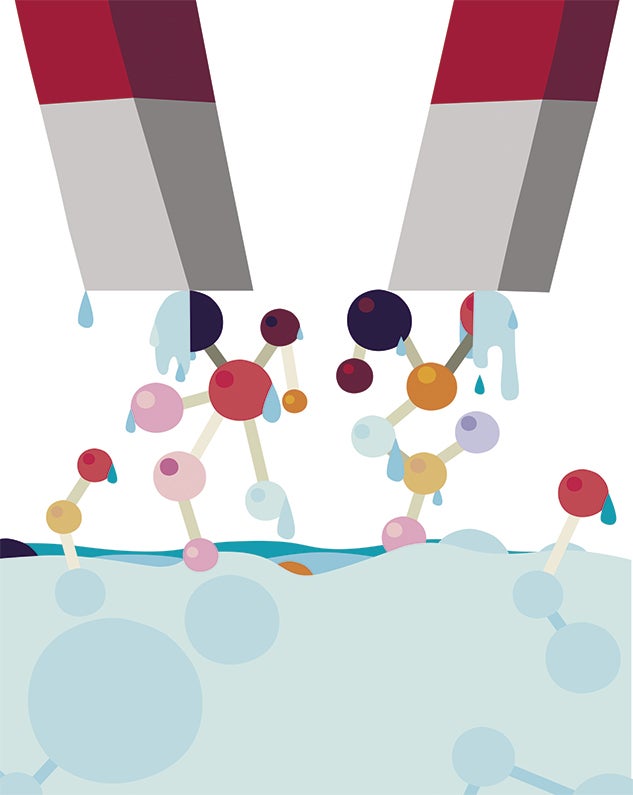

I’m a chemical engineer and chemist by training, and I use those skills to find new ways to clean contaminated water. You can physically remove some pollutants with filters or reverse osmosis, but others are far more persistent, and the only way to get rid of them is to destroy them through a controlled chemical reaction. I design nanoscale structures, called “catalysts,” that help kick-start that process.

One of the big questions I’m trying to answer is how to break down a class of molecules called per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS. Because the molecules they’re made of are nearly indestructible, they resist grease, oil, water and heat. After they were invented, large companies like DuPont, Dow and 3M started making them for household products like nonstick pots and pans, which people loved. Today, there are at least 4,000 different PFAS compounds used widely in fabrics, cookware, food packaging and firefighting foams.

About 20 years ago, government regulators and scientists realized that some of those molecules could be harmful for human health. They can leach out of landfills and factory sites and accumulate gradually in aquifers. Long-term exposure to them can cause cancer, slow down the body’s immune system and damage entire ecosystems — and since they last for hundreds of years in nature, there’s no real way to get rid of them.

I want to figure out how to create a substance that removes PFAS from water easily.

My lab recently developed a way to do that for a single PFAS compound called perfluorooctanoic acid, or PFOA, but there are still 3,999 other PFAS pollutants to deal with. How can we break down all of those different PFAS chemicals in water safely and easily? How can we seek out those molecules underground or in an aquifer and destroy them effectively? How can we make nanotechnology and materials work for us? That’s what gets me up in the morning. — As told to David Levin

Michael S. Wong is the Tina and Sunit Patel Professor in Molecular Nanotechnology.