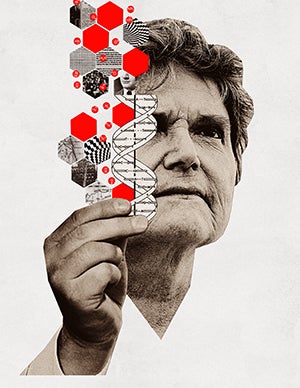

The DNA Detective

A lifelong love of science and fascination with family roots have served Colleen Fitzpatrick well as she works to unlock the mysteries of criminal cold cases.

By Dick Anderson

Colleen Fitzpatrick ’76 grew up surrounded by living history. “I was very close to all of my grandparents,” the New Orleans native says. “I knew some of their brothers and sisters and aunts and uncles quite well, and my grandparents often spoke to me about the ones who had already passed. As I got older, I was more formally researching, asking questions on my own and getting motivated to interview people in the family.” That precocious interest in family roots, combined with an inborn knack for scientific inquiry, developed into a career in forensic genealogy — or “CSI Meets Roots,” to borrow the name of her popular talk. Using every resource at her disposal, from photographs and databases to DNA registries, Fitzpatrick made a name for herself working on some of the biggest genealogical mysteries in American history, from Abraham Lincoln’s DNA to Amelia Earhart’s whereabouts.

But it’s a different kind of mystery — of the John and Jane Doe variety — that has galvanized the efforts of scores of genealogical sleuths scattered across the landscape. Fitzpatrick is the co-founder, along with fellow genealogist Margaret Press, of the DNA Doe Project, a nonprofit humanitarian initiative that aims to identify deceased persons whose fate is lost to their loved ones. It’s a team effort led by dedicated volunteers, all connected through the internet and social media and riding the wave of interest in genealogy made affordable by the likes of 23andMe and Ancestry.

Over the last 2 1/2 years, the project has solved 14 Doe cases — 10 Janes and four Johns — through the collective efforts of more than 80 volunteers using advances in DNA technology and an ever-expanding online DNA database to solve previously unsolvable mysteries, many of which date back decades.

Working out of her home in Fountain Valley, California, Fitzpatrick spends her days tracking cases, sending DNA off for lab work, shepherding cases through the system, talking to the media and even doing a bit of genealogy herself. Since 2010, her for-profit enterprise, Identifinders International, has worked roughly 120 cold cases, helping to solve “about a dozen,” she says. “I hand leads to the detectives working the case, and they have to run with those leads.”

At any moment the phone might ring, adding to her caseload. “Somebody might call and say, ‘We found another woman in the ditch who has been strangled. We only have her hands and her torso. Can you do anything?’”

Upon reflection, she adds, “I may not bring that up at the next cocktail party.”

A Budding Scientist

“I came from hardworking, smart people, but I really came from nowhere,” says Fitzpatrick, a descendant of Irish immigrants. “My dad was a florist; my mom was president of the mothers’ club, and they had three kids to raise besides me. My parents wanted their kids to succeed but didn’t know what to do about me.”

Going to an all-girls Catholic school “where science was not emphasized,” Fitzpatrick nurtured her hunger for archaeology, astronomy and other sciences through different channels, including a National Science Foundation-sponsored summer program in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. She won countless science awards growing up and was handed a box of trophies at her senior awards ceremony: “When they announced the science award, I stood up before they said my name.”

It was another science award that made her Rice education possible. “I had been accepted by Rice, and my dad went there to see if he could get a scholarship for me because we were just really more than broke — my grandmother was ill and we had medical bills to pay. And they told him no.”

Then a telegram arrived, addressed to Fitzpatrick, that would change her life. “It said, ‘Congratulations, you won one of 10 top national prizes in the Tomorrow Scientists and Engineers Competition sponsored by Humble Oil. And your prize is a scholarship to the college of your choice,’” she recalls. The $6,000 prize “would not even pay for books these days, but that covered Rice tuition for four years.”

Physics to Forensic Genealogy

After graduating from Rice with a B.A. in physics, Fitzpatrick went on to earn a master’s degree and Ph.D. in nuclear physics from Duke University. In 1989, she founded Rice Systems (named for her mother, the former Marilyn Rose Rice) in her garage. It was an optics company that specialized in high-resolution laser measurement techniques for the National Science Foundation, NASA and the Department of Defense. Her company moved to an office complex in Irvine, California, and employed a host of scientists and contractors before closing in 2005. “As a small, woman-owned business,” she says, “it was hard to survive in the business and political environment at that time.”

As her company was winding down, Fitzpatrick found a welcome distraction in writing a book that combined her love for genealogical research with her background in the sciences. Together with her co-author and domestic partner, engineering and business management consultant Andrew Yeiser, Fitzpatrick opened a publishing company and released “Forensic Genealogy” in 2005 with an initial run of 500 copies. The weekend that her business was liquidating its office furniture, she attended her first genealogy conference in Portland, Maine, with her book in tow. “I shared a table with a DNA company we were working with, and I couldn’t stop selling books,” she says. “This was the start of a whole new career.” Over the next few years, “Forensic Genealogy” sold 20,000 copies.

In 2006, “Forensic Genealogy” attracted the attention of an investor working in unclaimed real estate. He was trying to locate a married couple in Taiwan to buy a house that had gone into escrow with the state of Florida because the owners had not paid their back taxes. Using her online research prowess, she quickly located the property’s former owners — in Taipei.

But in the interest of getting a bigger return on her effort, she told the investor, “‘Since Taiwan is so hard to research, I want to charge you an arm and a leg for this, but I will make you a sporting deal. Give me four days to find these people, and I want the arm up front. If I can’t find them in four days, I’ll give you the arm back. But if I do find them, I want the leg to go with it.’ The hard part was waiting 3 1/2 days to tell him I had success,” Fitzpatrick says.

That work was the beginning of Identifinders International, the business she co-founded with Yeiser. Over the last 14 years, Identifinders has tackled a wide scope of cases, from Baby Does and Holocaust survivors to murder suspects and military IDs. In 2008, working with the Armed Forces DNA Identification Laboratory, Fitzpatrick was a member of the team that identified the remains of the “Unknown Child on the Titanic” as Sidney Leslie Goodwin, a 19-month-old English boy. Though Yeiser passed away in 2016, Fitzpatrick’s work with Identifinders still occupies about half of her research time.

A New Career

It was only after she met Margaret Press, a retired software developer and published mystery writer living in Sebastopol, California, that the DNA Doe Project came to be. Press took an interest in genealogy from her grandmother, a founding member of the Southern California Genealogical Society. “She lived in Long Beach, and she was always doing genealogy when I would go down and visit her,” says Press, who grew up in Los Angeles.

“Like a lot of people, I started out helping others who didn’t know who their parents were,” she says. “My family tree was very compelling, but not nearly as significant as helping a friend find out who their parents were.”

In 2017, about a year into her retirement, Press read “Q Is for Quarry,” Sue Grafton’s 2002 novel based on the real-life unsolved murder of a Jane Doe found near a quarry off California’s Highway 1 in 1969. Unable to shake her own interest in the case that inspired Grafton’s novel, Press reached out to Fitzpatrick, having stumbled onto her public Forensic Genealogy Facebook group some months earlier. As Fitzpatrick tells the story, “I had already worked about 100 cold cases when Margaret approached me, because there was a big discussion in the genealogy world about using ancestry.com in cold case work to identify John and Jane Does.”

Soon after their initial conversation, they learned of a genealogist who had been eager to test his late father’s DNA. After he recovered a tissue biopsy belonging to his father, he sent that tissue to an independent lab for a process called whole genome sequencing at a cost of roughly $1,500. Using the results, he was able to use bioinformatics software to replicate ancestry-like data that he uploaded to GEDmatch, an open data genomics database and genealogy website that Fitzpatrick calls a “watering hole” for genealogists.

“He had compared himself and his cousins and his brothers against his dead father’s manufactured, synthetic data” — the product of whole genome sequencing — “and it worked like a charm — like the guy was alive,” Fitzpatrick notes. “If we could do the same thing for the DNA from John and Jane Does, couldn’t we use the same techniques to identify them?” And the DNA Doe Project was born.

Testing the Theory

Now they only needed some John Does to test their theory. Using her law

enforcement contacts, Fitzpatrick secured DNA samples from a couple of test cases that had long gone cold. One was “Joseph Newton Chandler III.” Chandler’s suicide in 2002 led authorities in Eastlake, Ohio, to discover that he had stolen the identity of a dead child 24 years earlier. The real Chandler perished in a car crash in Texas in 1945.

“Ninety percent of Chandler’s DNA had been degraded,” Fitzpatrick says. But genetic genealogy tools were created for use with data generated from “fresh” DNA. So to test whether the tools worked with compromised DNA, Fitzpatrick degraded her own 23andMe results along with that of her late partner using software she created.

“I checked the list of matches I had for the data generated before and after I degraded our DNA results, and the two lists were almost the same.” The result told her that the tools could work with compromised DNA. Late one night, after six months and roughly 3,000 hours of work, a volunteer identified Chandler as Robert Ivan Nichols, originally from New Albany, Indiana. It was March 6, 2018 — one year after U.S. Marshal Peter J. Elliott shared Chandler’s DNA sample with Fitzpatrick and Press. As Forensic Genealogy’s Facebook group lit up with the news, Fitzpatrick awoke Press with a voicemail. “I still have the voice message from Colleen,” Press says.

The next morning, Press and Fitzpatrick called Elliott with the news and filled him in on all the records they had found — where Nichols had lived and the names of his wife, sons and parents. “The marshal was completely floored at how much information we had about somebody he thought would absolutely never be identified,” Fitzpatrick adds.

It would be nearly 10 weeks before Elliott went public with the news. “We couldn’t say anything about it right away,” Fitzpatrick says. There was some suspicion that Nichols was the “Zodiac Killer,” the serial murderer who terrorized the San Francisco Bay Area in the late 1960s. In the interim, the DNA Doe Project cracked its second case: that of Marcia King, aka “Buckskin Girl,” a 21-year-old murder victim wearing a buckskin leather jacket when she was discovered in a ditch outside of Troy, Ohio, in 1981.

“That one was easy. It took five hours,” Fitzpatrick says. Buckskin Girl was their first publicly announced case. She and Press flew out to Ohio in April 2018 for the press conference, but their names were mostly left out of the ensuing press coverage.

By the time Chandler’s real identity came to light at a June 21, 2018, press conference, their breakthrough was eclipsed by the arrest nearly two months earlier of 72-year-old Joseph DeAngelo in Citrus Heights, California. Working with police investigators, retired patent attorney turned genealogist Barbara Rae-Venter identified DeAngelo as the notorious “Golden State Killer” by running a recovered sample of crime scene DNA through GEDmatch — the same methodology used by the DNA Doe Project.

“I give full credit to Barbara — she’s done some great work,” Fitzpatrick says. Even so, she admits that “it’s kind of disappointing” that the DNA Doe Project didn’t get its due for being first to use genetic genealogy to crack cold case mysteries. “We are among the real pioneers,” she says.

The “Belle in the Well”

Like many who take an interest in forensic genealogy, Lee Bingham Redgrave and Anthony Lukas Redgrave of Athol, Massachusetts, began by solving their own genealogical mysteries. “I never knew my father, and my wife is an adoptee,” says Anthony. “Eventually we started finding adoptee cases a little too easy.”

The Redgraves were among the first volunteers to join the DNA Doe Project. Their detective work helped crack the Jane Doe case in Lawrence County, Ohio, known as the “Belle in the Well” — a woman’s body found decomposed and unrecognizable inside a cistern in 1981. The Belle in the Well was one of the earliest pilot cases for the DNA Doe Project, submitted in June 2017 after a forensic anthropologist who reopened the case in 2009 met Fitzpatrick at a conference.

“That one was a real doozy,” Fitzpatrick says of “Belle” — and the most time-consuming of the cases DNA Doe Project has solved so far. Belle’s family seemed to originate from a community where the practice of marrying within one’s own family was commonplace, yet Belle’s parents did not appear to be related. In January, the Redgraves noticed a distant relative of Belle’s appear on GEDmatch — someone living in Canada of German ancestry. Going through that person’s family tree, they discovered a relative who had immigrated from Germany to the United States and had married a woman from West Virginia. They turned out to be the parents of Louise Virginia Peterson Flesher — the Belle in the Well — born in 1915 in West Virginia. It was a theory borne out after Flesher’s daughter consented to a DNA test.

“The DNA Doe Project takes up most of my day,” says Anthony, who uses his background in instructional design to create the DNA Doe Project’s forensic genealogy training programs for law enforcement personnel and agencies. The online course is designed to be finished in about three weeks, and has had 28 graduates since February. Together, Anthony and Lee are currently overseeing 15 cases in the system as team leads for the DNA Doe Project. “I get overwhelmed by the fact only a handful of people are able to do what we do,” says Anthony, who is currently working toward a doctorate in transformational leadership at the University of New England. “I feel like a superhero who can only help people after they die.”

Privacy and DNA Cases

Although both Fitzpatrick and Press envision an unending stream of John and Jane Doe cases in the future — the National Missing and Unidentified Persons System estimates that 4,400 unidentified bodies are recovered in the United States each year — the ethics of using a public genetic genealogy database have come under fire in the wake of the Golden State Killer case.

“If police can use genetic databases to catch killers — even those who are distant relatives of individuals who have submitted their DNA — then perhaps more people will sign up to share their DNA,” read a May 2018 editorial in Nature. “But they should be told that this is a possibility, and be given the choice to opt out.”

In 2019, after police in Utah uploaded crime scene DNA from an assault case to GEDmatch — which had previously only allowed police to investigate homicides or rapes — GEDmatch changed its terms of service to accommodate a wider variety of crimes, including nonsexual assaults, while also requiring users to opt in to allow their results to be available for law enforcement searches.

“We have to find a balance between privacy and the need for public safety,” Fitzpatrick says. GEDmatch’s move “was the right thing to do,” she adds, “because this is a negotiation process between two groups that have traditionally never really worked well together. Law enforcement didn’t want genealogists to interfere with their investigations, and genealogists didn’t want law enforcement to use their DNA. So now there’s a reason to work together.”

Hollywood, meanwhile, wants to get in on the DNA detective business. Hardly a week goes by when Fitzpatrick or Press doesn’t field a pitch from a producer eager to make a documentary series on the pair. “It would be such a distraction,” says Press, whose true crime book, “A Scream on the Water” — based on a 1991 murder in her own neighborhood — inspired a 1996 segment on the series “Unsolved Mysteries” and an episode of A&E’s “City Confidential” two years later.

A more plausible scenario would be working as technical consultants on a fictional series — think “CSI” meets “Murder, She Wrote.” “There could be a television show,” says Fitzpatrick. But for now, she’s content focusing on the work they are doing: “Solving cases. Helping people. Bringing relief, information and release.”