A Murder, A Mystery and a Vision

An aging millionaire’s fortune was at stake, and an unlikely pair — a lawyer and a valet — had murder on their minds.

The plan was simple enough: Slip mercury pills into the victim’s meals, forge a will and, after the poison did its work, split the cash. Once the body was discovered, it would appear as if the elderly man had died peacefully in his sleep. The murder was calculated, cold — and if not for a sharp-eyed bank employee and the tenacity of a Houston lawyer, a grand vision for “an Institution for the Advancement of Literature, Science, Art, Philosophy and Letters” would have died, too. The visionary, of course, was William Marsh Rice.

Rice was born March 14, 1816, in Springfield, Mass. At the age of 15, he dropped out of school and went to work as a clerk at a local grocery store. In his early 20s, Rice opened his own store with the financial backing of his father. He soon sold the business and used the profits to purchase a shipment of goods to be delivered by sea to Galveston, where Rice planned to make his fortune in the newly formed Republic of Texas.

Upon arriving in Galveston, Rice learned that the vessel carrying his goods had been lost at sea, leaving him completely broke. His luck, though, would soon change. Rice possessed an impressive talent for knowing a lucrative opportunity when he saw one. He made a series of successful partnerships, founded several profitable companies and eventually became one of the richest men in Texas.

Rice married twice and, tragically, was widowed twice. His first wife, Margaret Bremond, died in 1863 almost a month before her 31st birthday. Rice’s second wife, Julia Elizabeth Baldwin, died in 1896, but not before she signed a secret will leaving half of the couple’s estate to her own beneficiaries, contradicting Rice’s will that left the bulk of the estate to the Rice Institute.

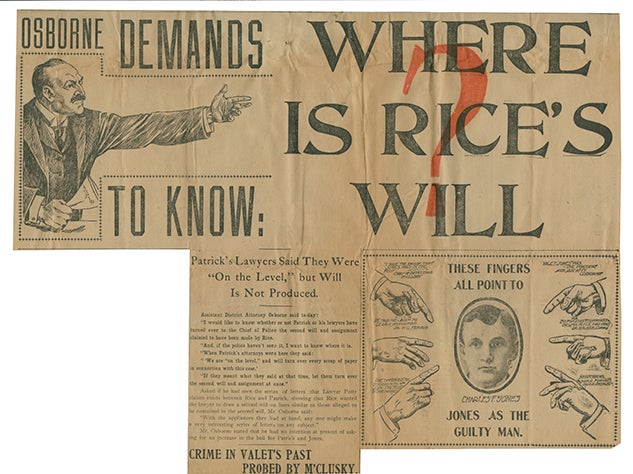

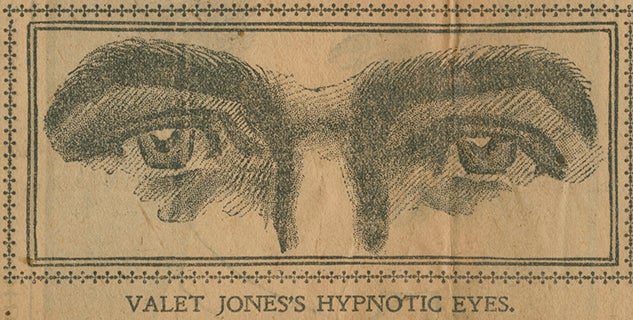

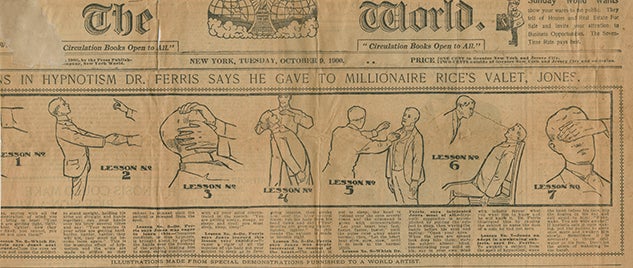

During the resulting estate battle, Albert Patrick, a lawyer working on behalf of Elizabeth’s executor, met Charles Jones, Rice’s valet. The two hatched a plan to forge a will leaving most of Rice’s estate to Patrick, murder Rice and steal his millions. The Great Galveston Hurricane of 1900 put Rice’s Texas holdings in jeopardy, however, and Patrick and Jones needed to act quickly before too much money was lost. They abandoned the daily dosage of poison in favor of fast-acting chloroform. On Sept. 23, 1900, Jones murdered Rice with a chloroform-soaked sponge while he lay sleeping in his New York City apartment.

In less than 24 hours, Patrick and Jones’ plan began to fall apart. It started with a forged check made out to “Abert Patrick.” An observant bank clerk caught the misspelling and alerted bank management. Capt. James A. Baker Sr., Rice’s longtime lawyer and trustee of the Rice Institute, was soon notified of his client’s death, the suspicious check and the new will. Everything pointed to foul play. With the help of a handwriting expert, along with a damning court exhibit consisting of glass plates bearing photographic reproductions of the identical forged signatures, Baker was able to prove that the will was fake. The autopsy uncovered signs of arsenic and mercury poisoning.

Patrick was found guilty and sentenced to death — though, surprisingly, he was later fully pardoned and released — while Jones was released after providing testimony against his co-conspirator. Ultimately, a settlement was reached with Rice’s late wife’s family and the Rice estate was safe once more. On Sept. 23, 1912, the 12th anniversary of Rice’s murder, Rice Institute’s first class matriculated and a grand vision was realized.

— Daniel Ford