In the Eye of the Hurricane

What’s a county judge got to do with emergency management? In Harris County — just about everything.

Fall 2017

By Franz Brotzen

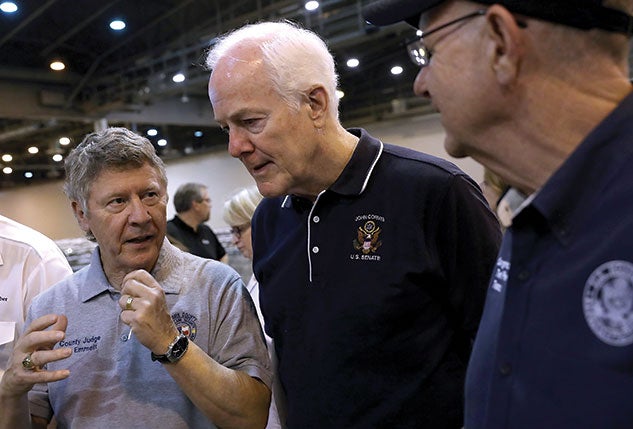

In 2007, former Texas legislator Ed Emmett ’71 was appointed county judge of Harris County — the most populous county in Texas and now the third-largest county in the U.S. He was elected to the position the next year, then re-elected twice. His title is a bit of a misnomer — Emmett neither presides over a court of law nor is he an attorney. The office leads the commissioners court, the powerful governing body that presides over the Harris County government, and manages the county’s office of emergency management. During the storm, Emmett was often the face of the emergency communications, delivering critical updates in a calm and no-nonsense manner. It was the fourth — and by far the worst — major storm emergency he’s managed since becoming the county’s chief executive. On Sept. 22, Franz Brotzen ’80 sat down with the former president of Lovett College for a conversation about that experience and what changes Emmett sees for the area in Harvey’s wake.

What are the responsibilities of a county judge in Texas?

Most people don’t understand that under Texas law, the county judge in every county is the director of homeland security and emergency management. So I’m in charge of emergency management for the county, including the city of Houston and the 33 other cities within the county, plus the unincorporated part of the county. I’m not a [court of law] judge; I’m not even a lawyer. In any other state, I would be called a county executive. We interact with the state and FEMA and all those organizations. Even requests to declare an emergency come from the cities to the county, and then I push them on to the state. Back when Bill White was mayor and Hurricane Ike was coming, I understood that people know what a mayor is — they don’t necessarily know what a county judge is. So it’s important that Mayor Turner and I do joint press conferences. I’ve seen where the state says this, the county says that and the city says something else. People don’t want to see that. They want everybody to be on the same page.

During a weather crisis, how do you monitor what is happening?

Harris County has the largest and the best emergency operations center in the country. We’re all in one room in the TranStar facility — it has 98 workstations and a command operation. On Aug. 24, we went to Level 1 — or full activation — and stayed that way for more than a week. We have all of the county and city officials, METRO, state officials, nonprofits like Red Cross, law enforcement, military assets, federal assets and the Coast Guard in there. We are all NIMS certified, which is the National Incident Management System. We can monitor all the air traffic and the marine traffic. So when an emergency comes, everybody knows their job, and I become the face of that operation. We also have a website, readyharris.org, that had over 3 million individual users during Harvey.

Were you expecting more of a wind event or a rain event, or both?

We were always preparing for a rain event, with some wind and no storm surge. We knew it was going to be bad. I don’t think anybody could have thought it would be as bad as it was. When Harris County got almost 52 inches of rain, that’s a national record.

What were some of the challenges early on?

Through no fault of anyone, a lot of the assets that were supposed to be coming in to help from the state and Red Cross couldn’t get here because the highways were flooded. On Sunday [Aug. 27] during the day, that was when I said, “OK, if you have a boat and you want to help, call this number.” There were two reasons behind that. One, as I understood it, people were going to put their boats in the water to help whether I asked them to or not. Consequently, that meant we were going to try and coordinate it a little bit. But the other reason was that no government entity had enough boats to rescue people, and the waters were so high that high-water vehicles couldn’t work.

shelter, Sept. 4. photo by Justin Sullivan / Getty Images News

When do you make the decision to tell people to evacuate?

Of course, that was one of the big issues: “Why didn’t you evacuate?” We never considered it. To do a mass evacuation, you have to start days in advance. Everybody saw that during Rita in 2005. You have to put everybody on the road. Days in advance would mean we’d shut down all businesses in Harris County.

In addition to being in charge of the flood emergency, you had a family member in harm’s way.

My daughter’s family was evacuated from Braes Heights when their street was flooded and many homes were taking water. In their case, they were lucky. Their garage flooded, but the water did not get into their house.

What went right during the whole emergency?

What went right was everybody cooperated. We didn’t have a lot of finger-pointing, and we were able to use assets that we wouldn’t normally — like private boats and UPS — when Harris County opened the NRG shelter. That was a spectacular thing. Early on, Angela Blanchard, CEO of BakerRipley [formerly Neighborhood Centers], set the tone. She said, “Look, we do not have evacuees; we have guests.” They had a Main Street, a grocery store and a pharmacy. They had basically a field hospital at NRG.

Our team cooperated with the city, METRO, TxDOT — everybody — so we prevented many deaths [in underpasses known for previous deaths]. During Harvey, as with previous rain events, the overwhelming majority of deaths occurred when people drowned in or near their vehicles. That is why it is important for people to stay inside.

One story you may not know: Remember there was an elderly couple during the Memorial Day flood who the Houston Fire Department rescued? The [rescue] boat overturned and they drowned. Their grown children were trapped this time. I got a text from Martin Cominsky, who’s the president and CEO of Interfaith Ministries. He told me that story, and we were able to make sure they got out. Some people might say, “Why are you prioritizing?” Sometimes you do.

What would you do differently?

I would make sure that we were in charge of the shelters so we wouldn’t have to scramble around and borrow things to make sure people get out of harm’s way. We have almost 20,000 people in Harris County who are members of the Community Emergency Response Team program, or CERT. They’re trained as volunteers. Now that we’ve identified this need for boats, high-water vehicles and other assets, we’re going to bring those into the CERT process.

Not Just the Cajun Navy?

They were helpful, but we had other people show up in bass boats and didn’t have enough life preservers. We want to formalize a civilian boat corps to augment the first responders because governments are never going to have enough boats to respond.

Everyone in the country has heard about the Addicks and Barker

reservoirs and how they flooded neighborhoods after the storm itself. What’s to be done there?

Well, this is a broader issue. Downtown Houston was inundated in 1929 and 1935. That led to the creation of the Harris County Flood Control District in 1937 and the building of the Addicks and Barker reservoirs by the Corps of Engineers. And of course those were built so far out of town that people thought they were going to protect everybody. But now we have people living around them and even have homes built inside the reservoirs! That should never have happened.

Before 1984, when the county was given some authority over building in the incorporated areas, the county had no way of stopping people — you could build wherever you wanted to. And those [homes] are now built in the 500-year floodplain. Well, we’ve had three 500-year events in the last two years. That tells me either our definition of a 500-year event is wrong or maybe we’re going to be free and clear for the next 1,500 years. I’m not betting on the latter. I think we have to recognize we’re living in a changed environment.

What are your priorities now?

We are developing a comprehensive flood control plan that will seek new reservoirs, completion of projects on all watersheds, a major home buyout program for those areas that continually flood and a renewed push for the county to have more control over development. On a broader front, I will continue to push for a different method of governance and funding for Harris County. It is

basically an urban area saddled with an out-of-date structure and finance.

What does #HoustonStrong mean to you?

You know, those of us in Texas tend to say, “We take care of ourselves.” I think the truth is most places do. Another example of that is the Hurricane Harvey Relief Fund, which was formed by me and Mayor Sylvester Turner and has raised more than $70 million. The funds are being distributed to nonprofit organizations that provide direct relief to the victims of Harvey. None of the funds go to government agencies.