Suffrage Pioneer

A century ago, a member of Rice’s first graduating class became a leader at the center of the women’s suffrage movement in Washington, D.C.

On a frigid Monday in early 1919, Elizabeth Green Kalb ’16 dressed herself head-to-toe in white before leaving her room at the National Woman’s Party (NWP) headquarters. It would have been a short walk for Kalb, an alumna of Rice’s first graduating class, down Jackson Place to Pennsylvania Avenue, where she and her fellow suffragists stood in front of the White House, copies of President Woodrow Wilson’s speeches clutched in their hands.

The women lit the president’s words on fire, then let them burn in metal urns. The protest was one of the first so-called Watchfire demonstrations held in the nation’s capital in January and February 1919. NWP members picketed to pressure Wilson into lobbying reluctant senators to pass a women’s suffrage amendment to the Constitution, giving women the right to vote. Wilson announced his support for the amendment a year earlier, but NWP members believed his lobbying efforts to be lackluster at best.

On that particular day, Jan. 13, Kalb may have been among the 25 NWP members attacked by a mob led by schoolboys. When the women lit new fires in nearby Lafayette Square, the mob destroyed banners at NWP headquarters and pulled down the bell in the building’s balcony that tolled during the women’s watch. Eighteen suffragists, including Kalb, were arrested. Kalb was imprisoned for several days in the district jail where she fell ill, possibly with the Spanish flu.

“I couldn’t even be lifted up to a sitting posture without something inside of me cutting off my breath at once,” Kalb wrote in a letter to her mother, Benigna Green Kalb. “Two tobacco-y guards and a very onion-y one” lifted her out of bed onto a stretcher and she was brought home in an ambulance.

Kalb’s ordeal, and her broader efforts for women’s suffrage, of course ultimately paid off. One hundred years ago, on Aug. 18, 1920, Tennessee became the 36th state to ratify the 19th Amendment, decreeing states could not discriminate at the polls on the basis of sex. Eight days later, the secretary of state certified the ratification, ending almost a century of protest. Texas was the first Southern state to ratify the amendment.

The Owl Who Beat Texas

Born in Ohio in the 1890s, Kalb was one of 59 young men and women to enroll in Rice Institute’s first class Sept. 23, 1912.

Students without cars took a trolley to Rice, riding the South End streetcar to Eagle where they boarded a shuttle car known as the “Toonerville Trolley” to campus. At the front gates off Main Street, a paved street connected to a dirt and shell road that students traversed to registration. Classes began the next day.

Like all students, Kalb would have enrolled in English, German, physics, mathematics and chemistry. By the end of the first term, one-fifth of the first freshman class had failed so many subjects they were asked to withdraw. Kalb remained. She joined the Elizabeth Baldwin Literary Society, a debating and literary group for women, and her crowning achievement came in 1915 when she won first place in the Texas Intercollegiate Peace Association’s third annual oratorical contest, where she presented an original essay.

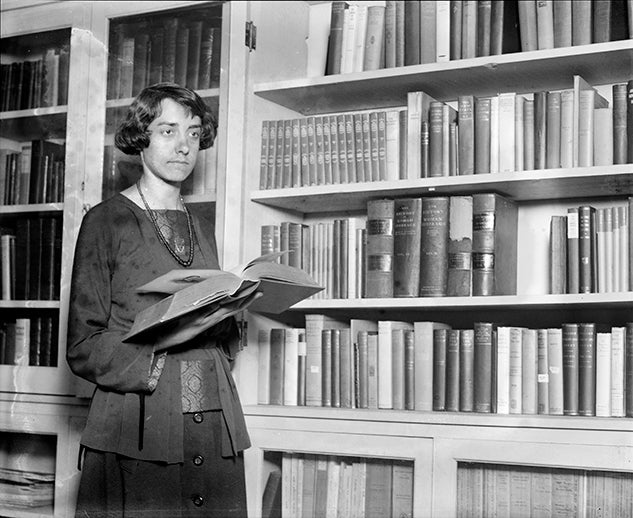

Elizabeth Kalb pictured in 1920. Photo from the National Photo Company Collection / Library of Congress

“If our civilization is to outgrow war, we must first outgrow our old narrow, self-centered, half-savage conception of National Honor, and endow coming generations with the heritage of a greater and nobler ideal,” Kalb wrote in her essay, “The Problem of National Honor.” A poster pinned on a bulletin board in the Sallyport the following day pictured Kalb, deeming her “The Owl Who Beat Texas” to mark the first time Rice beat the representative from the University of Texas.

Shirley Marshall, a management consultant for nonprofits whose parents were friends with Kalb and her husband, says, “The award was a big deal for her because she didn’t see herself as a public speaker. Her true passion was writing and editing.”

At Rice’s first commencement in 1916, Kalb and classmates celebrated with dances, a play, a tennis tournament and a garden party. Kalb graduated with distinction and wrote a dedicatory poem for her class to mark the occasion.

“Rice was clearly a very formative place for her,” says Marshall, who inherited some of Kalb’s diaries and correspondence from her parents. “It really gave her confidence.”

Committed to Voting Rights

After graduation, Kalb tried to find work as a writer or editor. Ultimately, she moved to Washington, D.C. after her mother encouraged her to join the suffragist movement. At first, Kalb volunteered. But then, in 1918, the NWP offered her a job as editor of The Suffragist, the NWP’s weekly journal.

Kalb moved into the bustling NWP headquarters where she mingled with suffragist leaders like Alice Paul and Lucy Burns. Unlike other suffragist groups, the NWP was laser-focused on a single goal: a national amendment supporting women’s right to vote.

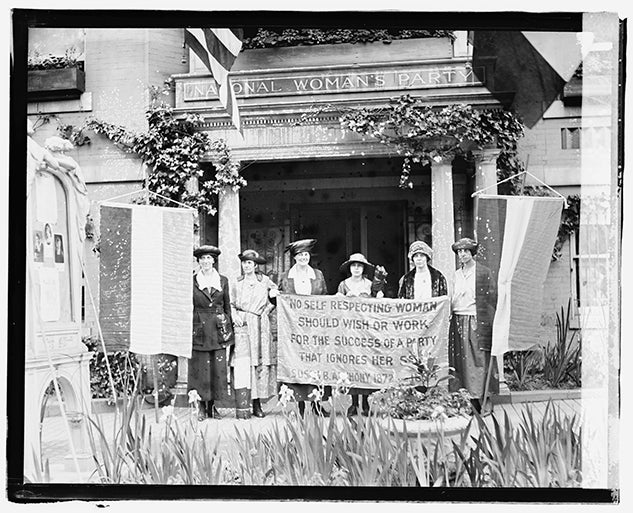

Kalb’s mother joined her, and they often picketed together. One iconic photo shows Kalb, her mother, Paul and other suffragists outside headquarters holding a sign with Susan B. Anthony’s famous quote, “No self-respecting woman should wish or work for the success of a party that ignores her sex.”

After her arrest in 1919, Kalb became one of 166 women awarded the “prison pin” from the NWP for time spent in jail. And even after the 19th Amendment was passed, Kalb continued with her commitment to voting rights, helping Native American and Chinese immigrant women who were unable to vote.

Today, Kalb’s legacy lives on at Rice at a time when issues such as who gets to vote and what it means to be a U.S. citizen are still just as relevant.

When Kalb donated a copy of NWP member Doris Stevens’ 1920 book “Jailed for Freedom,” which documents the work of the NWP, to Rice in 1920, she wanted future women to remember the suffragists’ struggle and their ultimate success.

On the fly leaf of the book tucked away in the Woodson Research Center’s archives, Kalb wrote in black ink, “To The Girls of Rice, Past and Present, This Book is Affectionately Inscribed.”

— Deborah Lynn Blumberg