Dickie Kerr's Legacy

On the centennial of baseball’s biggest scandal, the memory of a little-known Rice coach stands tall.

By Richard Johnson

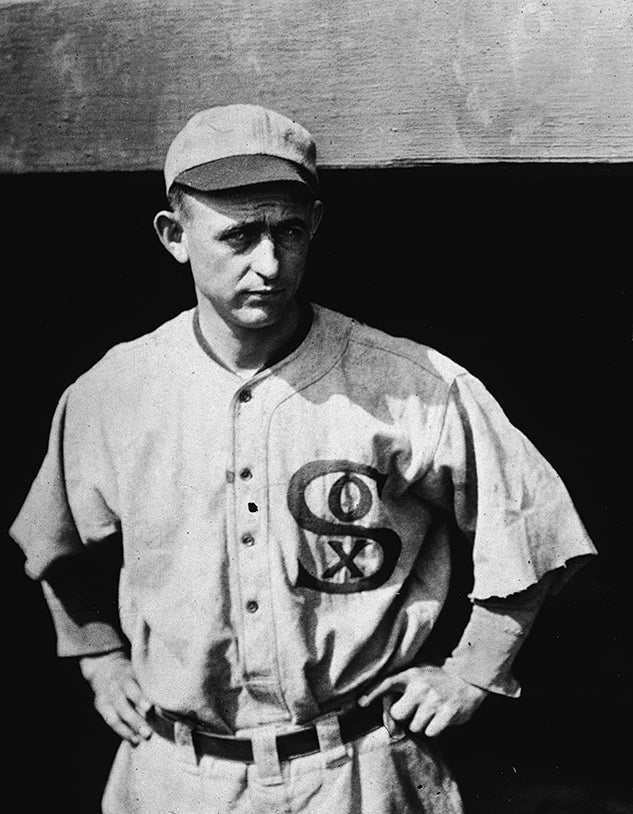

In the annals of Rice baseball, dating back to 1913, only one of the school’s 20 head coaches failed to last an entire season. A certain “Wee” Dickie Kerr — who stood 5 feet, 7 inches tall and weighed 130 pounds — took charge of the Owls in late January 1928 and was gone by the middle of April.

Kerr departed after a poor start that included a pair of tough defeats at the hands of The University of Texas, making him not much more than a footnote in Rice sports history — except that in 2019 he rates special consideration.

This fall, baseball laments its low point — the 100th anniversary of the 1919 World Series between the Chicago White Sox and Cincinnati Reds, when eight Chicago players were paid by gamblers to lose. But the “Black Sox” centennial also commemorates that same Dickie Kerr, who pitched brilliantly for Chicago in the tainted series, winning two games while his teammates were sloughing off. When he died of cancer in 1963, legendary New York Times sportswriter Arthur Daley declared Kerr “a symbol of integrity” and a “shining beacon of righteousness.”

The scandal led to a gust of fame for the pitcher, but by 1927 he was adrift, a struggling, itinerant baseballer. That’s when Rice Athletic Director Claude Rothgeb hired Kerr as baseball coach. “Coach Kerr is a master flinger of the horsehide and his knowledge should stand the Institute chunkers in good stead,” noted The Rice Thresher. The new coach was enthusiastic: “We ought to have a good club,” Kerr said. “In fact, I won’t have nothing but a good club.”

When he died of cancer in 1963, legendary New York Times sportswriter Arthur Daley declared Kerr “a symbol of integrity” and a “shining beacon of righteousness.”

A few weeks later, the Thresher reported that Kerr was focused on “speeding up the infield’s handling of the ball” and that “a month of strenuous practice such as Kerr is dishing out to the team members should make a world of difference in the type of play offered.”

But the regular season began with two one-run defeats to the powerful Longhorns. Losses piled up and Kerr’s tenure abruptly ended.

Rothgeb attributed the departure to “a conflicting contract with an oil company near Houston, whose team he manages in a semiprofessional league.” The Corsicana Daily Sun quipped: “Another fairly good reason is that the Owls have lost nine and won one thus far in the Southwestern Conference baseball race.”

John Sullivan, an assistant director of sports information at Rice, doubts the early losses triggered Kerr’s exit. “He was a very well-respected baseball man and not someone who was fired or quit when the Rice college season was not going too hot,” said Sullivan.

In 1940, Kerr became manager of the Daytona Beach Islanders, a St. Louis Cardinals farm team. One of his players was a 19-year-old pitcher with uncertain prospects named Stan Musial. Kerr recognized Musial’s uncommon ability as a hitter and played him in the outfield between pitching starts. When Musial injured his shoulder, putting his pitching career in doubt, Kerr — who’d become a father figure — persuaded him to turn his attention to the outfield and the batter’s box. The result was more than 3,000 big league hits and induction into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1969. Stan “the Man” Musial stepped up to the majors, while Kerr was soon out of professional baseball.

In March 1949, Rice football coach and Athletic Director Jess Neely brought the old left-hander back to Houston to assist coach Harold Stockbridge for a season. The Thresher noted that he helped top hurler Tom Hopkins ’49 show “remarkable improvement.”

Kerr never sought praise for his 1919 heroics, once saying, “It always did seem funny to me that so much fuss could be made about a man’s being honest.”

In 1958, Kerr was holding down a nondescript office job in Houston when Musial surprised his mentor with a birthday present — a house. News of the gift revived memories of Kerr and cemented his status as a living symbol of sports integrity. Kerr never sought praise for his 1919 heroics, once saying, “It always did seem funny to me that so much fuss could be made about a man’s being honest.”

On May 14 of this year, Rice played the University of Houston in a crucial game at the home of the minor league Sugar Land Skeeters; in the press box of Constellation Field is a bronze statue of Kerr. Sullivan paused at the sculpture, which was dedicated in 1966 at the Astrodome and has had a nomadic history. “I remember thinking, ‘I hope coach Kerr will bring his old team some luck tonight,’” Sullivan said. Perhaps he did. Rice defeated its crosstown rival, 2-1, to clinch the Silver Glove Trophy.

Richard Johnson is a freelance writer based in Michigan and the former editor of Crain Communications' "Automotive News." He's also the author of "The Knuckleball Club: The Extraordinary Men Who Mastered Baseball's Most Difficult Pitch."